John Philip Edmond - "The Mind behind the Haigh Hall Library"

John Philip Edmond was born in Aberdeen in 1850 and died in Edinburgh in January 1906, but the most defining thread in his adult life was a friendship that reshaped his career: his relationship with James Lindsay, later the 26th Earl of Crawford and 9th Earl of Balcarres. What began as a scholarly exchange grew into one of the most productive bibliographical partnerships of the late nineteenth century.

Edmond first wrote to Lindsay in 1883 after learning of the extraordinary collections at Haigh Hall, - the vast Bibliotheca Lindesiana. Lindsay’s reply was warm and generous, and when the Library Association met in Liverpool the following year, he invited Edmond to stay at Haigh and assist with the librarians’ visit.

James Ludovic Lindsay

James Ludovic Lindsay

The encounter proved transformative. Despite the social distance between a self-made Aberdeen printer and a Scottish aristocrat, the two men discovered an immediate intellectual kinship.

Their friendship was built on shared enthusiasm rather than formality. Edmond wrote that they were “scarcely ever separated,” united by “the inexhaustible topic of books.” He recalled nights spent exploring Haigh’s long corridors by candlelight, Lindsay sometimes atop a ladder while Edmond held it steady, both of them exulting in the discovery of rare Scottish tracts. In scholarship, they met as equals.

The relationship soon evolved into sustained collaboration. Lindsay encouraged Edmond’s bibliographical research and publications, while Edmond’s methodical mind and tireless work ethic became indispensable to organising and interpreting the Crawford collections.

John Philip Edmond

John Philip Edmond

Edmond helped plan exhibitions, advised on acquisitions, and gradually took on the demanding scholarly labour of turning Lindsay’s vast holdings into accessible catalogues.

When Edmond left the family printing business in 1888 to pursue librarianship in London, his work with Lindsay intensified.

He assumed editorial control of major Crawford-sponsored projects, including the Catalogue of Ballads in the Bibliotheca Lindesiana and the Handlist of Proclamations.

These were monumental bibliographical enterprises, and Lindsay entrusted Edmond fully with their execution. Edmond even influenced their production, recommending the University of Aberdeen Press.

In 1890, Lindsay brought Edmond to Balcarres in Fife to catalogue the family library there, further weaving him into the Crawford family’s intellectual life.

The following year marked a turning point: Edmond entered a formal agreement to work full-time at Haigh Hall and moved into Moat House, in Copperas Lane.

Moat House

From 1891 onward, much of his scholarly output was devoted to cataloguing the Crawford collections.

His works on broadsides, newspapers, and books in numerous European and Asian languages helped make Haigh one of the most thoroughly documented private libraries in Britain.

East Library

East Library

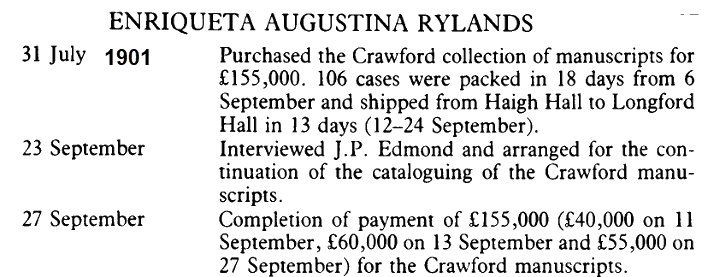

Yet the arrangement was not without personal cost. Haigh’s isolation and damp climate affected Edmond’s already delicate health. Lindsay’s frequent absences and major decisions — such as the sale of important manuscripts to Enriqueta Rylands — could be dispiriting for a man who had invested so much of himself in the collections.

Extract from an article by D.A Farnie

Extract from an article by D.A Farnie

Nevertheless, their mutual respect endured. Lindsay supported Edmond’s family, contributed to his children’s education, and later provided a crucial testimonial when Edmond applied for the Librarianship of the Signet Library. That recommendation — famously sent by telegram while Lindsay was briefly ashore in Bermuda — played a key role in securing Edmond’s appointment.

In many respects, Edmond became the scholarly engine behind the Crawford collecting vision. Lindsay supplied the resources, ambition and access; Edmond supplied the scholarship, organisation and extraordinary capacity for sustained work. Together, they transformed great private accumulations into bibliographical tools that still underpin modern research.

John Philip Edmond’s collaboration and friendship with James Lindsay, Lord Crawford spanned about 23 years — from their first meeting in 1883 until Edmond’s death in January 1906.

During that time their relationship grew from an enthusiastic scholarly friendship into close professional cooperation, including full-time work at Haigh Hall from 1891 onward.

Their partnership remains a striking example of intellectual collaboration that transcended class boundaries — forged not in drawing rooms, but in library galleries, on ladders among the shelves, and in the shared excitement of rediscovered books.

Thanks to Jim Meehan

Sources:

Findmypast. Signet Library, Edinburgh