Margery Booth – The Operatic Spy

Introduction

In the Second World War, Margery Booth, a Wigan born internationally acclaimed opera singer found herself in the heart of Berlin spying for the Allies. If it weren't for Margery’s name being mentioned in the personal memoirs of World War Two soldier spy John Brown DCM, which came to light after his death in 1964, her story would have gone untold.

A biography based on Brown’s memoirs, entitled ‘In Durance Vile’ was revised and edited by a friend and fellow prisoner of war, New Zealander John Borrie in 1981. Although world famous in her time very little was known of Margery’s private life. Also the very nature of the intelligence services makes detailed information difficult to come by concerning her time in Germany during the Second World War.

Using public records, newspaper reports, and personal memoirs it is now possible to look in more detail at her family background, main characters in her life, singing career, war time exploits and the political and military situation in Europe at the time.

Following further research of the MI5/MI9 files held at the National Archives and also the brilliant and extensive research by Robert Vervaik for his 2024 book 'The Traitor of Colditz' it has been possible to revise and update the 2021 version of this article.

Humble Beginnings

Margery Myers Booth, the only child of Levi Booth and Florence Beatrice Myers Tetley was born 25 January 1906 at 53 Hodges Street, Wigan, a bay windowed terraced property off Park Road to the north of the town centre.

Margery's birth place, 53 Hodges St, Wigan.

Census and parish records show that Margery’s paternal line the Booths were living in Bolton as far back as the late 1700’s. Margery’s grandfather Levi Booth, who was born in 1838, started a business as a wholesale brush manufacturer in 1860, working from 41 Cheapside, off Newport Street in Bolton. He married Yorkshire girl Caroline Roberts Jackson on 6 August 1863 at St. John the Baptist church in Halifax. They were to have seven children, four boys and three girls.

The couple lived in Bolton for a few years, but soon after their son Joseph’s birth in 1867 Levi moved his family and business to Wigan. He is listed in the 1869 Slaters Trade Directory as a brush maker living at 47 Wallgate, opposite the Victoria Hotel, calling his business the ‘Wigan Brush Works’.

The census of 2 April 1871 finds Levi, Caroline, two year old son Richard and two day old baby daughter Sarah living above their shop in Wallgate. At the time of the census their two older children Walter and Joseph were staying with their grandparents near Halifax. It was at 47 Wallgate that Margery’s father, also named Levi was born In 1875. He was destined to become a brush maker like his father.

Levi later moved his premises from number 47 to 18 Wallgate, nearer to Market Place in the centre of town. Here he advertised that he was a brush wholesaler and retailer, also selling baskets, washing lines, cord and twine. A passionate angler himself, he was also a fishing tackle dealer.

His business became a success and by the time of the 1881 census he was employing four workers at his Wallgate workshop. As he became more wealthier he moved his family from over his shop to 29 Upper Dicconson Street. Then later to a larger property, Sicklefield House off Wigan Lane. More moves followed, firstly to Gathurst Lane in Shevington, then to Common Road in Parbold, located in the quiet countryside and away from the bustling Victorian industrial town that was Wigan. In 1906 he advertised in local newspapers that he was having a moving sale and relocating his business premises from Wallgate to 25-27 the Wiend, off Millgate.

Two years later In 1908 Levi was to lose his third eldest son Richard, aged 39 in tragic circumstances. Richard had been working as a commercial traveller for his father but had been in ill health for several years and had been unable to work for the previous month.

On Saturday 20 November Levi received a letter from his son dated the previous day, as a consequence the Leeds & Liverpool Canal near Richard’s home in Clarence Street in Ince was dragged. Richard’s body was found with two handkerchiefs tied around his legs. At the inquest held in front of Coroner Brighouse the jury returned a verdict of ‘Suicide while of unsound mind’.

His two older brothers had chosen to make their own way in life. Walter became a brewery manager in Bolton, whilst Joseph opened a shop in St. Helens selling general goods and brushes manufactured at the Wigan Brush Works. This left just Levi Jnr working in the family business in Wigan.

By 1911 Levi Snr and his wife Caroline, who was now blind had moved from Parbold back into Wigan. They were living above a shop at 25 Mesnes Street opposite the Market Hall, that their divorced daughter Sarah was running. She was selling brushes that her brother Levi Jnr was producing in the Wiend.

Levi Snr died in 1915 in Lytham St. Annes. He had served as a Wigan Town Councillor for over a quarter of a century, being elected to represent the All Saints Ward in 1886. He served on all the council committees and became a Borough Alderman in 1901. As well as sitting on the Borough Magistrate's bench he was also a churchwarden of St. Thomas CE church in Wallgate where for a time he was an overseer of the poor.

For over 30 years Levi was a member of the Independent Order of Oddfellows, a fraternal order, set up to provide care for the needy in a time before the National Health Service and the welfare state. As well he was instrumental in setting up the Wigan & District Amalgamated Anglers Association and was its first President.

Levi Booth Snr was buried in Wigan Cemetery in Lower Ince in a double grave alongside his six month old daughter Sarah who had died in 1874, and his wife Caroline who had predeceased him two years previously. His son Richard, who had tragically drowned in 1908 lies in an adjoining grave.

Maternal Roots

Margery’s mother Florence Tetley came from an old Yorkshire family that can be traced back to the 1680’s. In the 1800’s they were cloth merchants in the Bradford area. Margery’s maternal grandfather James Edward Tetley married a Manchester girl Sarah Elizabeth Myers in 1870. They then moved to Leigh and on the 1871 census are shown living at 71 Lord Street, James’s occupation is shown as a coal proprietor.

James then seems to disappear from the picture and his whereabouts are unclear, the next official record is his death, aged 58 on 11 May 1898 in Queensland, Australia. On the 1881 census Sarah is shown living with her parents Henry and Elizabeth Myers at 1 Florence Street in Hindley near Wigan, with her one year old daughter Florence.

Sarah remarried under her maiden name of Myers on 12 April 1882 at St. James CE church in Poolstock, Wigan. Her new husband, who she was to have three children with was Thomas Mort, a shoemaker and pawnbroker who had a business in Market Street, Hindley.

The census of 1901 shows that 22 year old Florence had left her step family and was once again living with her grandparents Henry and Elizabeth Myers in nearby Castle Hill. She married Levi Booth Jnr four months later on 17 July 1901 at All Saints CE church in Hindley. Five years later, on 31 January 1906 a notice in the births, marriages and deaths section of the Wigan Observer & Advertiser announced the arrival of Margery Myers Booth into the world.

The 1911 census shows five year old Margery and her mother Florence were now living with her great grandparents Henry and Elizabeth Myers at 90 Barnsley Street, a terraced property just round the corner from her birth place in Hodges Street. Margery’s father Levi is shown as being at the Wiend, his business address in Wigan on the night of the census.

Margery's father, Levi Booth Jnr (1875-1933)

Margery’s name appeared in the newspaper again when the Wigan Observer & District Advertiser dated 11 Jan 1913 showed Margery’s name amongst the list of all the school children invited to Mayor Edward Dickinson’s Juvenile Ball at the Pavilion Theatre in Library Street, Wigan.

New Life in Southport

By 1914 Levi had relocated his family to the Meols Cop district of Southport, moving into a semi-detached house at 87 Clifton Road. Levi commuted daily to his business in Wigan and Margery attended the nearby Norwood Primary school.

The first written record of Margery performing live is an article in the Southport Advertiser, reporting that she sang in an operetta at the age of eight in St. Luke’s church on Good Friday, 10 April 1914. The following year her great grandparents Henry and Elizabeth Myers moved from Wigan to live with them in retirement at Clifton Road.

Alas all was not well in her parents’ marriage and in 1918 they separated. Levi petitioned for divorce from Florence, on the grounds of her misconduct with a man named William Fairhurst at the family home in Clifton Road. Fairhurst was said to keep an off licenced house in Woodhouse Lane, Wigan. Levi told Mr. Justice Shearman that his wife had taken to drink and they then had entered into a deed of separation. A Decree Nisi was granted in 1919.

Margery’s parents both remarried in 1920. Her father married Ada Sidebotham in July at Hope Street Congregational Chapel in Wigan town centre. Ada had been living above his brush shop in the Wiend for a number of years. Her brother was Ezra Sidebotham, a printer of long standing in Wigan, he also had premises in the Wiend.

Her mother Florence married William Fairhurst, twenty years her senior at Ormskirk Register Office in September of that year. William, whose father was a publican had been in the brewery trade all his life and described on various censuses as barman, brewer, mineral water bottler, and publican. The 1921 census finds Margery living in Clifton Road with her mother and step father, whose occupation is shown as commission agent for Burtonwood Brewery of Newton Le Willows, near Warrington.

Margery’s talent as a singer had been recognised at an early age and it was after her mother’s second marriage that she was given the chance of professional training as an opera singer. She had inherited her singing talent from her father who had a fine treble voice. In his youth he had been leading soloist in the Wigan Parish church choir and was a member of Wigan Operatic Society.

At the age of 14 she started on the long road to stardom which would require dedication and years of hard work. Opera singers have to be extraordinarily disciplined, mastering the art of acting and stage presence. Being bilingual and the ability to sing in several languages is essential, therefore the study of foreign languages at music school is mandatory.

Margery firstly began a two year course of singing lessons in Bolton under the tuition of Welshman Richard Evans, an ex-miner from Ruabon near Wrexham. There then followed a move down to London for six months private tuition with professional singer Aileen D'Orme in Knightsbridge.

She then attended the prestigious Guildhall School of Music and Drama for a further two years training to perfect her contralto voice. In 1924 she won the Mercer Scholarship of 50 Guineas, which she repeated the following year, also gaining the Liza Lehman prize of ten Guineas.

It was whilst at the Guildhall School that she met and struck up a friendship with a young German student who was staying in the same digs. His name was Egon Strohm and he was in London studying English Language. They both went their separate ways to pursue their careers but were destined to meet again.

Journey to Berlin and Fame

On completion of her training Margery found it difficult to secure engagements and after an illness travelled to Switzerland in order to recuperate. It was here that she was advised to go to Berlin to pursue her dream of being a professional opera singer.

In 1928 she made a successful audition with the Berlin Staatsoper Unter den Linden (Berlin State Opera House). The iconic building, close to the Reichstag and Brandenburg Gate, and built by Frederick the Great in 1741 had just reopened after a two year refurbishment.

After a further six months training under the tutelage of the famous French soprano, Lola Artot de Padilla she signed a one year contract and made her first appearance in Berlin that year, a minor part in the opera La Tosca. Margery soon became a favourite with Berlin audiences. In 1930 she had a lead part in the new German opera Der Fremde Erde’, an honour rarely accorded to foreigners.

On 17 Aug 1932 the Lancashire Evening Post published a short article with the headline banner ‘A Southport Girl Who Sings in Berlin’, Margery is quoted as saying: 'I love coming back to Southport for a holiday, but I love Germany so much now that I would not like to leave it. If you have talent the German people will back you up, second rate is not sufficient, nor will they find excuse for an artist who is out of condition. The Germans don’t think the English have any talent and will only believe you are English when you have thoroughly convinced them'.

Little did Margery know that during the following year of 1933 events would unfold that would lead to Germany becoming a dictatorship, the destruction of Europe in the Second World War and the eventual end of her singing career. In a very eventful year, her mentor Lola de Padilla, whom she had served her apprenticeship under, died in Berlin on 12 April.

A few weeks later on 9 May her mother Florence died of cancer, aged 54. At the time she was living at 24 Lethbridge Road, the property her and William had moved to a few years earlier. She was buried in Duke Street Cemetery in Southport alongside her grandparents Henry and Elizabeth Myers who had died during the Great war in 1915 and 1918 respectively. Margery was the sole beneficiary of her mother's will which included the two properties of Lethbridge Road which her step father continued to live in and their old home in Clifton Road which was rented out for extra income.

Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933. It was through his love of classical music that Hitler’s and Margery’s paths were to cross a few months later. After five years at the Berlin State Opera she was now a principal singer and the only English prima donna in Berlin, singing in German, French, Italian and Spanish. That year she was invited to sing at the Bayreuth Festival in northern Bavaria, and was chosen to carry the Holy Grail in the opera Parsifal which opened on 22 July.

Adolf Hitler and his top Nazi officials attending the Berlin Opera House in 1936

Hitler had an almost fanatical devotion to the work of the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner, which to him represented everything that was good about culture in Nazi Germany. His attendance at the Bayreuth Festival was very well publicised by Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda.

Margery revealed in an interview with the Lancashire Daily Post in December 1933 that she had met Hitler and also Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia and his wife Cecilie, the Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. She told the reporter: 'I had dinner with Herr Hitler and the Crown Prince and his wife. I received a beautiful bouquet of red roses and the people I met were all very charming. The ex-Crown Princess introduced me to her friends as ‘her baby’ and has promised to promote a concert at Potsdam at which I shall sing'.

The Crown Prince or ‘Little Willie’ as he was known as, was a passionate devotee of opera. He admired Margery’s singing and they were to become firm friends, this friendship was to prove invaluable a decade later.

During a later interview with the Liverpool Echo in 1936 she recounts that after one of her performances she was presented to Adolf Hitler and said of him: 'He was perfectly charming and they talked about art and music'. Margery was to become one of Hitlers favourite singers.

Held annually in July since 1876 the Bayreuth Festival is a month long performance of operas presented by the Wagner family. Performances take place in the Bayreuth Festpielhaus, a specially designed theatre which Wagner personally supervised the design and construction of.

Wagner's Festspielhaus at Bayreuth, Germany

The overall Director was English born Winifred Marjorie (nee Williams) Wagner. Originally from Hastings in Sussex and orphaned at an early age, she was sent to live with relatives in Germany. She married 46 year old Siegfried, the bisexual son of Richard Wagner at the age of eighteen in 1915.

She took over the running of the festival after her husband's death in 1930 until the end of World War Two in 1945. A personal friend and supporter of Adolf Hitler, she maintained a regular correspondence with him. They had met in 1923, the year that Hitler was jailed for his part in the Munich Beer Hall Putsch.

She sent him food parcels and stationery in Landsberg Prison, on which it is thought he wrote his autobiography Mein Kampf. Her antisemitic views led to her joining the Nazi Party in 1926 and in the late 1930’s she served as Hitler’s personal translator during treaty negotiations with Britain.

Whilst Margery was performing at Bayreuth her father died on 12 August 1933 aged 58. He was buried three days later in Wigan Cemetery, Lower Ince, alongside his parents and sister Martha Annie who had died aged five and half months in 1874. Margery’s parents had both remarried in 1920 and by a quirk of fate she was to lose them both in the same year.

In late 1933 Margery was hospitalised in Berlin, after an operation she started a period of recuperation which included a visit back to Southport for a short holiday. The following year she was invited back to Bayreuth, this time with the solo role of a flower maiden in the opera Parsifal and of Flosshilde, and a Rhine maiden in the fourth part of the opera Götterdämmerung. In the lavish production 1,500 costumes were used and 800 people employed, including 137 musicians.

At the time no one was aware that Margery was unwell again and had sung at least twenty times at Bayreuth in agonising pain, this led to her undergoing surgery again. She wrote to her step father William from her hospital bed in Erlangen, just north of Nuremberg in Bavaria, telling him she had had an operation for an internal complaint.

Hitler expressed concern and gave orders that she was to be well looked after and Goering and Goebbels sent messages of sympathy. The Queen of Denmark also sent good wishes and invited her to her country to sing. It was after a two month recovery that Margery was fit enough to start singing again.

Recognition at Home

Although famous in Germany and on the continent where she sang in the capitals of Europe, Margery was up to now virtually unknown at home. After her success at Bayreuth this was about to change. In 1935 she was invited to sing at the Promenade Concerts, (more commonly known as the Proms), with the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Queens Hall in London. (the building was destroyed in the Blitz in 1941 and the Proms then moved to its new home at the Albert Hall).

The Proms Concerts were broadcast on the radio and soon Margery’s voice was to be heard in every home in the land. After years of hard work she was finally getting the recognition she deserved.

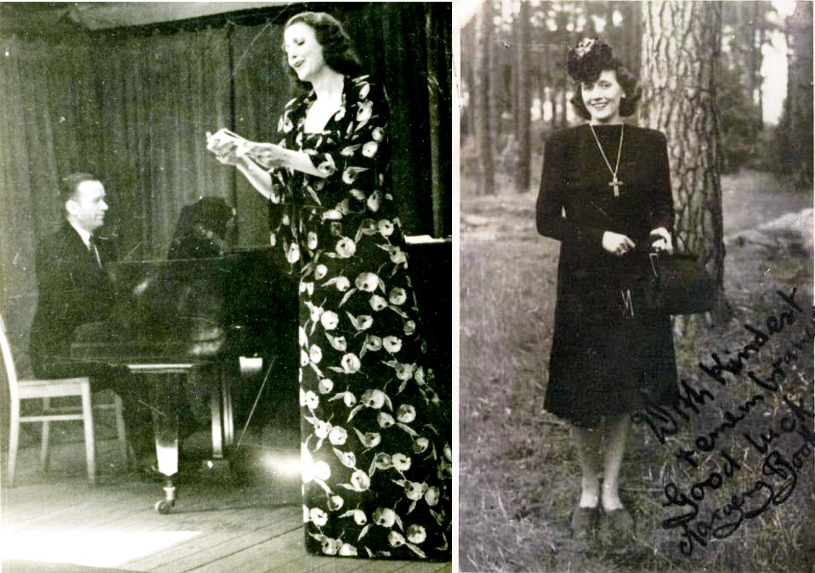

Margery at the height of her fame

Following her mother’s death from cancer, Margery became a keen supporter of cancer charities and research. Whilst based in London singing with the BBC Orchestra she took the opportunity to sing in a benefit concert at the Palace Theatre in the West End. This was in aid of the Holt Radium Institute which had amalgamated with Christies Cancer Hospital in Manchester two years previously. On 4 October 1935 she sang professionally for the first time outside of London when she performed at a concert at the Queens Hall, Market Street in her home town of Wigan.

Queens Hall, Market St, Wigan

Now at the height of her fame, 1936 was a busy year for Margery. Her new contract with the Berlin Opera stipulated that she spend seven months of the year in Berlin, singing on 60 nights during that time. During the other five months she was allowed to undertake tours. She finally fulfilled her greatest ambition of singing at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London on 27 April when she played the role of Magdalene in Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger. That year she was to create a record 23 appearances in the Covent Garden opera season.

It was after her successful debut in London that she announced her engagement to Egon Strohm, the German who she had first met as a student in London eleven years previously. She had hoped for a quiet ceremony in her adopted town of Southport four months later. However the news of her impending marriage leaked out. Not wanting to turn her special day into a media circus she cancelled the wedding indefinitely on the pretence that she was suffering from influenza.

She then discreetly rearranged for the wedding to go ahead the next day with only herself, Egon and the Vicar in the know, with the guests to be only informed at the last possible moment. Such was the secrecy that the officiating minister the Revd Canon Walter Morris, the Rural Dean of North Meols, was only given one hour's notice of the time of the ceremony. He married Margery and Egon by special licence at All Saints CE church in Rawlinson Road the next day, Wednesday 26 August.

Apart from Margery, Egon and the vicar, the only other people at the ceremony were her stepfather William Fairhurst who gave her away. Her cousin Marjorie Harrison who lived in Golborne and a neighbour from Lethbridge Road, fifty six year old Hubert Hunt, who was drafted in at the last minute to be the second witness. The best man, Thomas Forshaw, the Managing Director of Burtonwood Breweries at Newton Le Willows, near Warrington, the firm that her step father worked for, was unable to make it in time and missed the ceremony completely, only arriving in time for the reception at Margery’s family home.

Margery and Egon on their wedding day in 1936 with Terry her pet dog

Margery and Egon spent their honeymoon in Scotland before returning to Germany. In an interview with the Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser she is quoted as saying; 'When in England, nothing delights me more than go north and sing among my own people'.

It was reported that the following month she was to sail from Hamburg to America where she was to take part in the film adaptation of Aida, the opera by Guiseppe Verdi. On completion of which she was to travel to Cairo on a singing engagement before returning to Germany. (It is not known if she did travel to America as the film was not made. It was eventually produced in 1953 with Sophia Loren in the starring role. Her voice over was sung by Italian opera singer Renata Tebaldi).

German Husband

Margery’s new husband Dr. Egon Strohm was born 24 Oct 1904 in Trossingen in the State of Baden-Wurttemberg, the picturesque Black Forest region of south west Germany. His father Christian, was a member of a prominent brewing family and lived in a villa he had built in 1925 in Schwenningen, a town close by Trossingen where Egon was born.

The brewery in Trossingen was founded in the late 19th century and by 1904 it was known as Zum Baeren and owned by Johannes Strohm. It was renamed the Baerenbrauerei in 1920. The family operated a second brewery in the nearby town of Schwenningen with the owners being Gebrueder Strohm (Strohm Brothers). The brewery used a bear as its symbol and this became as famous as the animals on the State crest, a lion, stag and griffon.

A beer mat from the famous Bear Brewery in Schwenningen, Bavaria.

Egon didn’t enter into the family business but instead pursued an academic career. After University he moved to Berlin where on 14 August 1928 he married Elisabeth Martha Czaika. The marriage banns show he was a 23 old student living at Prinzregentenstrasse 83, Wilmersdorf in the south west suburbs of the city. Elizabeth, also 23, had been born in Lodz, Poland.

The marriage was not to last very long however and was dissolved in January 1930. Elizabeth reverted back to her maiden name, marrying for a second time to Raimond Fredrich Anton Spitzer on 4 April 1931.

During the 1930’s Egon worked as a journalist and radio reporter, whilst also studying for his Doctorate degree at Heidelberg University. In 1935 he qualified as a Doctor of Law and Economics after writing a dissertation for his PhD. entitled 'The British Empire as an Economic Entity'.

After Margery’s arrival in Berlin, which coincided with Egon’s first marriage, the pair eventually renewed their friendship from their student days in London and this led to a romance and marriage in England.

With her new contract giving her more freedom, Margery spent her time touring and commuting between Germany, England and America. She made a flying visit to Lancashire on 31 January 1937 to sing in a Manchester concert in aid of Christies Cancer Hospital and to visit Southport.

Egon met up with her in Southport after a trip to New York, arriving in Southampton on 16 March on SS Westernland, a German owned transatlantic liner, sailing the Antwerp, New York, Southampton route.

On Saturday 15 May she sang again at the Queens Hall in Wigan, fulfilling a promise she had made two years previously that she would return to her home town. The concert was to celebrate the Coronation of King George VI that had taken place three days beforehand. All benefits went towards Mayor Peter Winstanley's Royal Albert Edward Infirmary fund.

Interior of the Queens Hall, Market Street, Wigan

In July she was back in Southport for six weeks to stay with her step father in Lethbridge Road. Events led her to put all her engagements to one side, including a planned trip to the Isle of Man. Instead she spent her time frantically searching for her lost dog, a Terrier named Terry who had been missing for ten days. She put notices in shop windows, appealed in the newspapers and visited all the police stations in the area.

At Ormskirk police station they told her they had found a dog answering Terry’s description and had sent it to Walton dogs home. At Walton she found it had been sold to a Bootle man. At Bootle the buyer said he sold it to a man in the same street. The search ended in the home of the second buyer where Margery was able to buy Terry back.

War Clouds Looming

By 1938 the situation in Europe was deteriorating fast. Germany was now a fascist state with Hitler as Führer having full control of all political and military matters. The country had secretly been rearming for a number of years and war in Europe was now inevitable.

On 12 March German troops marched unopposed into Austria. In what's known as the ‘Anschluss’, Austria was annexed into Greater Germany. Hitler next set his eyes on the Sudetenland, the border regions of Czechoslovakia. On the pretext that German speaking Czechs were being victimised he demanded the region be handed to Germany by 1 October.

In August 1938 Egon started working for Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft (RRG), the Nazi German national radio network, at its main Berlin station. He was a commentator using the alias 'Scrutator' for the South East Asia Zone, and also an English language commentator on the Short Wave station. All broadcasting was under the direct control of the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda led by Joseph Goebbels.

The leaders of Britain, France, Germany and Italy met in Munich on 29/30 September 1938 and following a policy of appeasement by England and France the Czech President Edvard Benes was persuaded to submit to Hitlers demands. The next day the Sudetenland was annexed to Germany.

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned to England waving a worthless piece of paper declaring 'Peace in our time". Six months later however on 14 March 1939 Germany invaded the Czech lands and proclaimed the State of Slovakia, moving one step closer to all-out war in Europe.

Three weeks later on 7 April Egon departed on a trip to America, sailing on SS Bremen from the northern port of Bremen for the week long voyage to New York. The ship’s passenger list shows that Egon was travelling second class with three other radio reporters, two German and an Argentinian.

Their passages were paid for by the German Government. In what was probably a diplomatic trade mission, other passengers sailing courtesy of the government were businessmen and diplomats from Germany, Japan and other various countries.

The War Years

The United Kingdom declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, two days after the German invasion of Poland. Margery, by now a naturalised German citizen living in Berlin with a German husband was in the unenviable position of seeing the country of her birth at war with that of her husband’s and her adopted country of residence.

At the time Margery and Egon’s home was at Wieland Strasse 10, in the south west of the city in the Charlottenburg district, near Tempelhof Airport. For the first two years of the war life for the citizens of Germany more or less carried on as normal, with the Germans basking in their military victories. Margery continued singing at the Berlin Opera House and at the Bayreuth Festival.

Egon was now an established commentator at the Reichssender (Berlin National Radio) and was involved in the same English language output team as Lord Haw Haw and other traitors. He was right at the heart of the Nazi propaganda machine trying to influence British public opinion and morale

In 1941 the South East Asia Zone was absorbed into the Empire Zone embracing the entire English speaking world outside Great Britain and the USA. It's programmes were broadcast in English and Dutch. Egon was appointed section head with a team of twenty full time and ten free lance contributors.

It wasn’t until 25 August 1941 that Berlin suffered its first air raid when Tempelhof Airport was targeted by the RAF. After that, air raid precaution instructions were printed in the programmes at the Berlin Opera House.

The following year in September 1942 Egon was dismissed from his job at the RRG following an irregularity involving a trip accompanying Margery to an engagement in Budapest. He was later re-instated and allowed to work for the Zone as Chief Commentator.

The Berlin Opera House was badly damaged in a blaze caused by incendiary bombs during a raid by the RAF in October 1943, targeting the cultural area in the city centre. The raid was ordered by Churchill in retaliation to an attack by the Luftwaffe on Belgrade, the capital of Yugoslavia a few days previously.

The Opera House managed to open again for performances but was finally shut on the orders of Joseph Goebbels the next year. The last performance before closure that Margery would have been involved in was Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) on 31 August 1944.

During the war the Bayreuth Festival was turned over to the Nazi Party, which continued to sponsor operas for wounded soldiers returning from the front. These soldiers, as guests of the Fuhrer, were forced to attend lectures on Wagner before the performances. This arrangement continued up to 1944.

The town of Bayreuth was bombed by the United States Air Force in the latter stages of the war and two thirds of the town was destroyed. The home of the Wagner family 'Wahnfried' was damaged but the Opera House remained unscathed.

Whilst Margery was living in the heart of Nazi Germany her adopted home town of Southport was on the receiving end of visits from the Luftwaffe. The little seaside town had been considered a safe haven and was an evacuation centre with 15,000 child evacuees, not only from the Liverpool area but from afar as London.

The main target in the north west of England was of course Liverpool and the docks at Bootle and Birkenhead. Unfortunately Southport was on the flight path to and from Liverpool along the River Mersey. The town was only 13 miles from Bootle, a few minutes flying time. Crosby, Ainsdale and Birkdale were also on the receiving end of unused bombs jettisoned by aircraft on their way back to their bases.

Southport was to suffer eleven air raids in total over a period of nine months, the first on 4 September 1940. On the eighth raid on 8 April 1941 high explosive and incendiary bombs were dropped in the area quite close to Margery’s home in Lethbridge Road.

The vicarage of All Saints church where Margery and Egon had been married was damaged by a blast in the neighbourhood and the Vicar Canon Morris and his wife were slightly injured. In total during the raids on Southport 17 people were killed and 76 injured.

Margery's step father William Fairhurst died on 13 January 1943. He had last seen his step daughter in August 1939, just prior to the outbreak of war and last heard her voice in a German broadcast on an all Irish programme for American viewers. He was buried in a lone grave in Duke Street Cemetery in Southport. There have been suggestions that he disowned Margery completely because of her Nazi connections and the loss of life and damage caused by the bombing raids on Southport.

Probate records confirm that William did indeed cut her out of his will which was left to relatives in Wigan, and also a couple who shared his property with him in Lethbridge Road. In hindsight this was the only practical solution as it would have been virtually impossible for his executors to enact his wishes if Margery had been a beneficiary living in war time Germany.

Soldier Spy

Margery’s tale is inextricably linked to that of John Brown, the soldier spy, and his story has to be told in tandem with hers. John Henry Owen Brown was born in Battersea, London in 1908 to James Brown, a printer compositor by trade and Priscilla Francis (nee Martin) Brown.

A Cambridge graduate, John was employed as an accounts manager at Trumans Brewery in Brick Lane, East London. In early 1939 the thirty year old, nicknamed 'Busty Brown was married for a second time to Nancy Mason. In February of that year he joined a Territorial Army unit, 226 Battery, 57th Light Ant-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, whose headquarters were at Wimbledon.

Brown gained rapid promotion and by November 1939 held the rank of Staff Sergeant with the appointment of Battery Quartermaster Sergeant (BQMS). He was selected to attend a special Senior Non Commissioned Officer‘s course of instruction on how to gain intelligence once captured and in enemy hands.

The NCO's were encouraged to observe and remember details about enemy forces, such as troop strengths, morale, equipment, and tactics. Crucially they were taught a code that could be used in seemingly innocent letters home. Known as the 'HK Code', MI9 had developed it with the help of a Foreign Office expert called Hooker.

Brown's unit went over to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on 9 April 1940. He was captured on 29 May 1940 near Caestre, approximately 20 miles south east of Dunkirk, as the BEF withdrew to the channel ports as part of an evacuation plan. In a column of 3,000 prisoners he then trekked over 200 miles through France, Belgium and Luxembourg to Trier in Germany.

Here he was put in an overcrowded cattle wagon and transported 600 miles to Stalag VIII-B at Lamsdorf in Upper Silesia (now Lambinowce in modern day Poland). One of the largest POW Camp complexes in Europe, Lamsdorf was also the largest camp for British and Commonwealth troops, with about 48,000 prisoners passing through it's gates during the war.

BQMS John Brown, Royal Artillery at Stalag VIII-B , Lamsdorf

Not wanting to just sit the war out in a prisoner of war camp Brown decided that he could help the war effort by becoming a self-made spy. At the start of their captivity prisoners had to use POW postcards to send brief messages home, so he got his first letter home by bribing a Dutch civilian with extra rations in order to pass it to a Swedish sea captain sailing from the North German port of Stettin. The letter was intercepted by the MI9 escape and evasion network, who then got the Secret Intelligence Service, better known as MI6, to write to John on the pretence of being a friend or relative. Brown’s letters home were then intercepted and read by MI6 before being forwarded on to his wife Nancy.

At Lamsdorf he reasoned that if he were to gain any information useful to the Allies he would have to get away from the huge Lamsdorf camp which housed 5,000 prisoners. As a senior rank he was not obliged to work for the Germans, but he nevertheless volunteered to go to an Arbeitslager (work camp). He was transferred to Arbeits Kommando E/3 at Blechhammer (now Blachownia Śląska), one of seven POW camps in the area, some 40 miles to the east of Lamsdorf.

At Blechhammer, military prisoners of war of several nations, as well as thousands of Jewish slave labourers, who were housed at a nearby sub camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp, worked on two huge construction sites two miles apart. These would eventually become chemical plants using bituminous coal to produce synthetic oil. The prisoners at E/3 worked on Blechhammer North, their back breaking work consisted of clearing a forest site of tree stumps and stones and making access roads.

Brown decided early on that the best way to gain intelligence was to appear sympathetic to the German cause and get them to trust him. Striking up a good relationship with the Commandant of Blechhammer, Prince Waldemar Zu Hohenlohe-Öhringen was his first task.

Next he wrote an article entitled 'A Year Passes' in the POW weekly propaganda newspaper 'The Camp', it was published in Berlin on 7 September 1941 and distributed all over Germany. In it he praised the German authorities for providing all the necessities needed for prison camp life.

He knew that the Germans would notice his comments in the article and link it with the fact that before the war he had been in the British Union of Fascists, for which they had a list of members. At the same time he also knew it would make his fellow prisoners distrust him and even loathe him as a Nazi sympathiser.

Brown’s plan worked, in February 1942 he was transferred to Work Party 806 at Stalag III-D in south west Berlin for assessment by the Germans. One day he was taken to a house in Steglitz that contained men of many nationalities. it was being used as a holding centre for special prisoners, and was the prototype of a special camp the Germans were planning. He shared a room with Lieutenant Ralph Holroyd, an Australian whose German born mother was still living in Germany. Holroyd refused to co-operate with the Germans and was eventually sent back to an Oflag (officers prison camp).

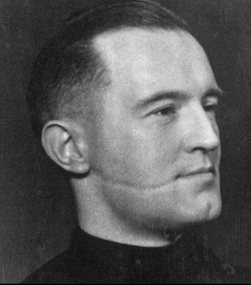

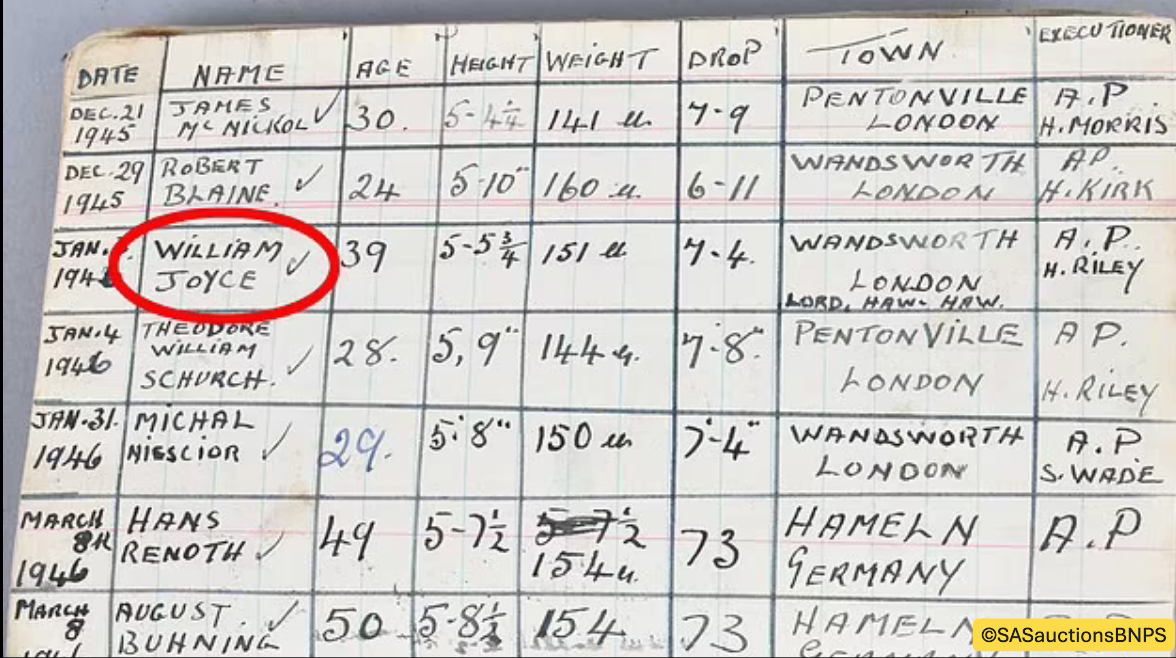

At the house he was interviewed by none other than William Joyce, the traitor who broadcast anti British propaganda on Berlin Radio. Brown had actually met Joyce before the war in the Fascist HQ Club in Kensington Road, Chelsea but did not disclose this to Joyce who did not recognise him.

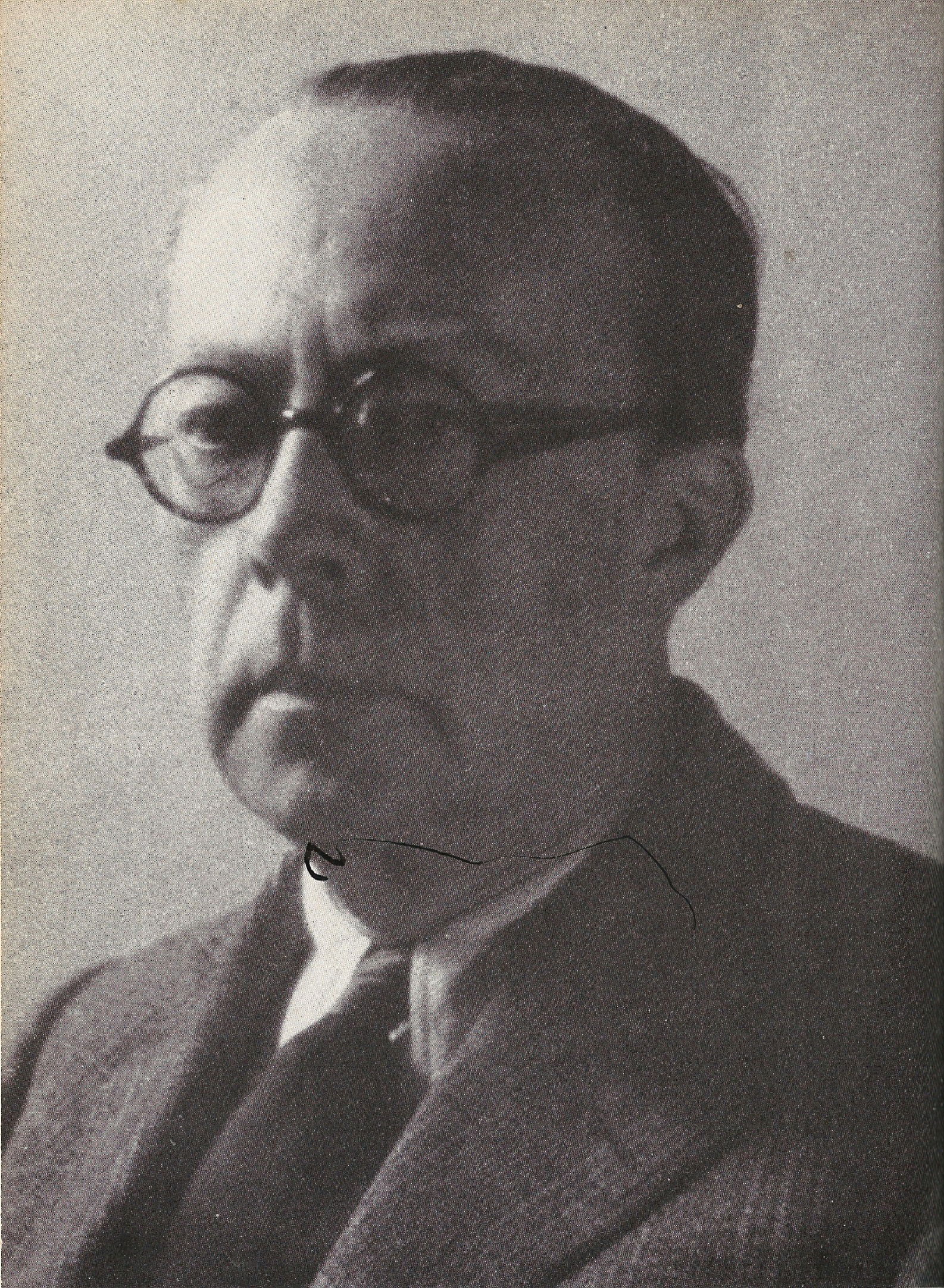

William Brooke Joyce was born 24 April 1906 in Brooklyn, New York. He was the son of an Irish Catholic father from County Mayo and an English mother who had been born in Oldham, Lancashire. When William was three the family returned to live in Salthill, County Galway in Ireland.

On 22 Oct 1924, whilst stewarding a Tory meeting in London he was attacked by a communist who slashed him with a razor on his right cheek, leaving a deep prominent scar from his ear to the corner of his mouth. In 1932 Joyce joined the British Union of Fascists under Sir Oswald Mosley, known for his talent for public speaking he swiftly became a leading speaker. Appalled however, by the violence of Moseley’s Blackshirts he left and started up a breakaway organisation, the National Socialist League.

In late August 1939, shortly before war was declared, Joyce and his wife fled to Germany. Joyce had been tipped off that the British authorities intended to detain him under Defence Regulation 18B. This regulation allowed internment without trial of people suspected of being actively opposed to the ongoing war with Germany.

Allying himself to the Nazi cause, he became a naturalised German citizen in 1940. Working for the Reichsrundfunk (German State Radio) in Berlin he broadcast anti British propaganda in an effort to undermine the nation's morale, urging Britain to surrender.He started his broadcasts with the introduction 'Germany calling... Germany calling'. Millions listened to him on their radios but he soon became an object of ridicule leading to him being labelled 'Lord Haw Haw' because of his affected upper class English accent. Owing to increased bombing raids on Berlin, Joyce broadcast from several locations including Luxembourg, Bremen and Hamburg.

His wife Margaret (nee White), born in Carlisle in 1908 was herself an ardent fascist. An accomplished speaker but less well known, she also had her own propaganda radio program. She was nicknamed 'Lady Haw Haw'.

Over the next few weeks Brown was allowed to go on walks round the city with a guard and he used the opportunity to do reconnaissance on potential targets and even managed to get close to Tempelhof Airport. However, William Joyce had taken a dislike to Brown and had given him a negative report. Major Heimpel of the Abwehr also did not trust him, so he was sent back to Stalag VIII-B at Lamsdorf. It wasn’t until August 1942 that he was able to get back to Arbeitskommando E/3 at Blechhammer.

In his letters home he passed on the locations of anti-aircraft defences, barracks and camouflaged sites in Berlin and the purpose of the construction work going on at Blechhammer South, namely the Heydebreck oil refinery. Known to Allied bomber crews as 'Black Hammer' the site was first bombed by the 15th US Army Air Force on 30 October 1943. Despite several bombing raids, production of synthetic oil eventually began at Blechhammer on 1 April 1944.

In March 1943 a message from London told Brown to try and arrange a transfer back to Berlin and obtain details of Englishmen broadcasting propaganda for Germany. After a carefully orchestrated row with the senior British NCO’s at Blechhammer he persuaded the Commandant to transfer him back to Stalag III-D in Berlin Lichterfelde, arriving on 12 June 1943.

Two new further sub-camps were created in May to June 1943, coinciding with Brown’s transfer to Berlin. Stalag III-D/999, in Kaun Strasse located in the Zehlendorf West district was to house officers. Stalag III-D/517 at Genshagen in the Ludwigsfelde district in the south west of the city was earmarked for other ranks.

Prisoners of war were selected by the Germans at random to go to these special camps for a month's rest. With better facilities they soon became known as 'holiday camps' by the POW's, a chance for a while to get away from the poor rations and hard work in the coal mines, quarries and factories and on the railways.

However the Germans planned to use these special detachments to separate potential collaborators from other British POWs. They particularly sought out former members and sympathizers of the British Union of Fascists.

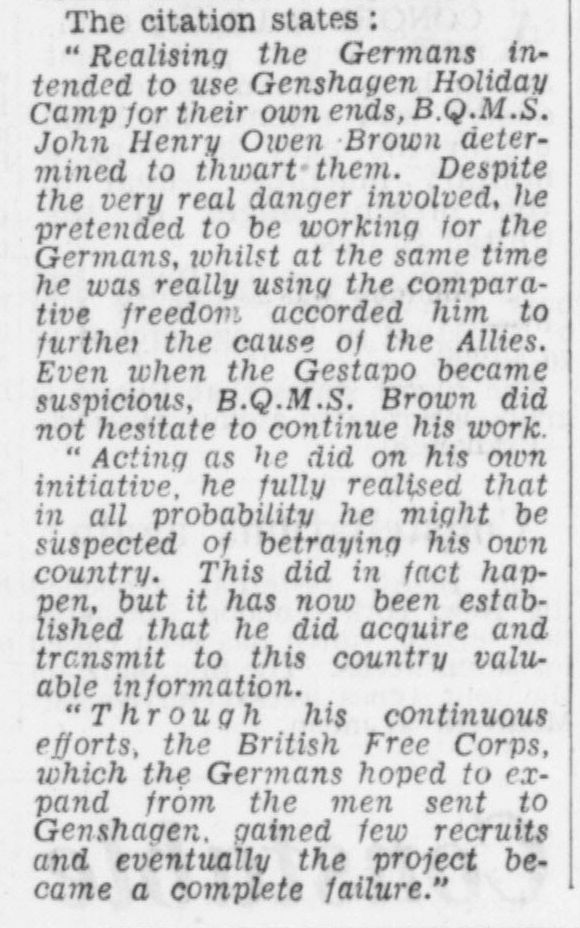

Brown was appointed by Dr. Arnold Hillen Zeigfeld, the head of the English Department of the German Foreign Office, and the architect of the holiday camps, to be senior British NCO in charge of administration at Special Detachment 517 based at Genshagen. A former Hitler Youth Camp, it had no watch towers and although it was surrounded by barbed wire, hedges and trees planted on the inside perimeter gave the illusion of an open camp.

The camp which could house a maximum of 270 men, came under the responsibility of the Foreign Ministry and Joseph Goebbels's Ministry of Propaganda. Camp security was run by the Abwehr, the German Military Intelligence, responsible for espionage, counter intelligence and sabotage. The guards, all English speakers so that they could eavesdrop on the POW's just carried holstered pistols instead of rifles, in an attempt to look less threatening.

The first batch of 200 holidaymakers arrived in April. Among these were his hand-picked staff of four who he could trust to help him run the camp, including his right hand man Jimmy Newcombe who he had requested to be transferred from Blechhammer.

As Vertrauensmann (man of confidence) he quickly made himself at home. He organised a black market to procure luxuries for the camp inmates and smuggled a radio receiver in so that he was aware of the course of the war. Brown ensured that they were looked after and got a well-earned rest away from normal POW camp life and work details

By a stroke of luck he discovered the purpose of the holiday camps. A young soldier at the camp, who Brown knew as Oscar England (this was an alias, his real name was Carl Britten) became seriously ill and the Gernan doctor didn't expect him to live. He confided in Brown that the reason to invite the prisoners to a rest camp was to recruit POW’s into the Britisches Freikorps (British Free Corps or BFC), a small unit of the Waffen SS raised to fight in the east against Bolshevism.. The Germans had been in discussions with Britten in an effort to persuade him to join the BFC. Brown then made it his mission to ensure that any attempts to form the British Free Corps would fail.

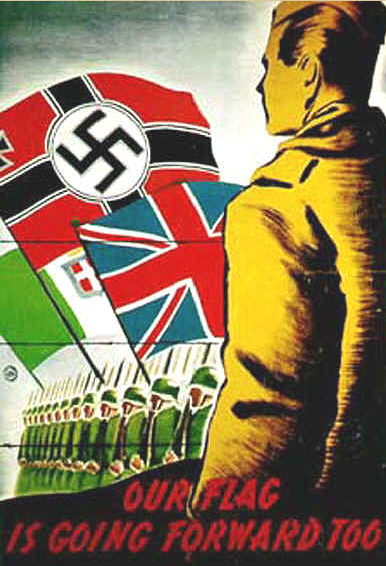

British Free Corps recruiting poster

Throughout all this time, while being distrusted by the British prisoners, Brown was gaining evidence of Englishmen broadcasting for the Germans. He acquired intelligence by bribing guards, talking to members of the BFC and from officials at the German Foreign Office where he was trusted.

His loyal staff also notified him of any sites of importance such as anti-aircraft positions or factories that they had seen on their regular shopping trips for camp supplies. Brown reported these back to London by coded letters as potential targets for bomber attacks.

Patriotic Ally

In an effort to show that German culture was superior to that of the Allies they brought in famous artistes to entertain the troops in the camp theatre. These included singers, pianists, violinists and dancers, Brown even arranged for the POW band and actors from Blechhammer to be brought to Berlin to perform the Mikado, the comic opera by Gilbert & Sullivan.

As British SNCO in charge Brown always met the entertainers beforehand. One day he was introduced to a singer by the name of Frau Strohm, during his conversation with her he realised that she was the famous English opera singer from Wigan, Margery Booth. Initially she was told that she could only sing in Italian, Spanish and German but when allowed to sing in English she included patriotic songs and always finished off with Land of Hope and Glory, much to the annoyance of the Germans. It was an unwritten understanding though that the Germans in the audience could get up and leave if they so wished.

However Margery moved in high circles and she had been given personal assurance by Hitler and Goebbels that they would deal with the matter personally if she were insulted because of her British birth. In a later interview in the Liverpool Echo in 1946 Margery said: 'I carried on singing but was never pro German. I sang for two hours every fortnight to the POW’s'.

A photograph has survived of her performing on stage at Genshagen, she is wearing a full length dress with poppy motifs, a point not lost on Brown. Realising where her loyalties lay he struck up a friendship and eventually revealed his plans to gain intelligence about British collaborators. In his memoirs he says, 'I was extremely moved the first time I heard her sing but I did not know then I was to have to trust her implicitly'. Margery was about to enter a world of intrigue, espionage and danger.

Margery Booth at Genshagen POW Camp © Trevor Beattie

For the next year and half Margery helped Brown in his intelligence gathering mission, She was in contact with top officials of the Nazi Party and diplomats and was in an ideal position to gain important information. As well as aiding Brown, she hid a Jewess in her flat for nine months and helped other evaders. She took considerable risks, and if her activities had been uncovered she would have faced certain death.

Barney Roberts, a Tasmanian who was at Genshagen for a holiday, met Brown who showed him his room. On the wall was a signed photograph of a famous opera singer. Roberts thought it was the opera singer Elisabeth Schwartzkopf but it was almost certainly a photo of Margery as Brown told him it was a personal gift from a wonderful lady.

Prior to meeting Brown, Margery had separated from Egon, their marriage being later dissolved. (Margery's close friend Dorothy Martland later revealed that it wasn't a happy marriage and that Egon spent all her money). As a single woman again she was free to use her flat to help the country of her birth.

She regularly arranged for prisoners from Genshagen to visit the State Opera House with a guard to see one of her performances. Afterwards prisoner and guard would be invited back to her flat for a meal. One such prisoner was Signalman J. Uttling from Liverpool who had been captured on Crete. At Genshagen he was given the job of stage manager. Margery later complimented him on his work on the stage scenery despite having limited materials.

After the first batch of holiday makers had left Genshagen the camp was badly damaged in an air raid. Brown had told London of a Daimler Benz factory six miles away in the Marienfeld district that was manufacturing Mk III Panzer tanks. The plant was bombed but stray bombs fell on the camp as well. The permanent staff were sent to temporary accommodation while repairs were carried out.

Brown received a message from London asking him to verify the identity of Englishman John Amery who was broadcasting propaganda from Berlin and whose idea it was to form the British Free Corps. To do this Brown needed to get out of Genshagen and into the city, so persuaded Dr. Hesse of the Foreign Office to issue a special identity card (Ausweis) which allowed him out of camp unescorted.

The Germans provided civilian clothes which were kept in a wardrobe in the Kommandatur (camp administration centre). So not to antagonise his fellow prisoners further he left the camp in uniform with the clothes in a suitcase and changed in a field.

Through Thomas Bottcher (real name Thomas Heller Cooper) a member of the British Free Corps, Brown set up a meeting with John Amery at the Hotel Adlon, situated in the city centre opposite the Brandenburg Gate. While seeming sympathetic to his cause, he managed to get Amery to talk about his activities and reveal his identity.

John Amery was born 12 March 1912 in Chelsea, the son of Leopold Amery, the Secretary of State for India in Winston Churchill’s wartime cabinet. Coming from a privileged background he was sent to Harrow to be educated but proved to be a rebel and left after a year.

Amery turned out to be an eccentric playboy who carried his teddy bear everywhere with him. He had a love of fast cars and fast women and at one point had picked up 74 motoring offences. He tried a career in film production, setting up a number of companies, these ultimately failed leading to his bankruptcy in 1936.

Amery who was an ardent Fascist with a hatred of Jews and Communists then went to live in France with his girlfriend. His fascist views led to him getting involved with the Spanish Civil War and becoming a gun smuggler for General Franco. He remained in France after the German invasion in 1940, living in the unoccupied zone run by the Vichy Government.

In September 1942, Amery obtained a permit to visit Berlin and consulted with the German English Committee, a body set up to seek out fascist sympathisers among the British. He suggested the Germans should form a British anti-communist legion, one whose members would be native born Britons with right wing views and fascist sympathies. He called it 'The British Legion of St. George'. Hitler was greatly impressed by the articulate Amery and his ideas, even giving his permission for him to remain in Germany as a personal guest.

In 1943 Amery started to recruit for a unit aimed at employing 50 to 100 British men for propaganda purposes. He considered that a prime source for such recruitment would be among disillusioned inmates of the PoW camps in Germany. However the Germans called the proposed new unit the British Free Corps, belonging to the Waffen SS. Amery was sidelined to propaganda radio broadcasts and in late 1944 travelled to Northern Italy to support Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been ousted from power the previous year.

Now with the freedom of the city, Brown was able to rendezvous with Margery outside of the camp. He visited her flat and they would meet up at the Berlin Opera House and also the Cafe Vaterland, a nightclub in Potsdamer Platz in central Berlin. The Cafe, the largest in the world, was inside the enormous Haus Vaterland (House of the Fatherland), a themed pleasure palace based on the Coney Island entertainment area in New York.

It contained a cinema, numerous themed restaurants and ballrooms and could accommodate 8,000 people. It was badly damaged, along with the Berlin Opera House in the bombing raid on 22 November 1943 that destroyed much of the city centre. It was in the Cafe Vaterland that Brown met a German girl by the name of Gisele Maluche, who was to become his mistress. Her flat was a useful base to have in the city from which to carry on his dangerous game of espionage.

The Mysterious Lieutenant Calthrop

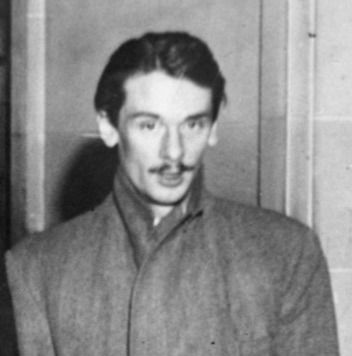

On 20 April 1944 a Lieutenant from the Royal Sussex Regiment, who went by the grand name of John Boucicault de Suffield Calthrop arrived at Genshagen. He told Brown that with the authority of Lieutenant Colonel Kennedy the Senior British Officer at Rotenburg, he was to take control of the holiday camp, but that Brown would remain as man of confidence. After conversations with him Brown became suspicious of the newcomer and of his reasons for being at a camp for other ranks when officers had their own holiday camp at Schloss Steinburg. It was to be a complication that Brown could have done without

Calthrop was commissioned into the 5th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, a Territorial Army unit in September 1938. His regiment went to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force on 7 April 1940. He was captured in Belgium on 31 May and sent first to Oflag VII-C located at Laufen Castle on the Austrian border, then the following year transferred to Oflag VI-B at Warburg in Westphalia.

In September 1942 he was transferred yet again to Oflag VII-B at Eichstatt in Bavaria. It was here that Calthrop who had a background in theatre and film first made approaches to the Germans and expressed an interest in being involved in the film industry. He made them aware of his thoughts on the Jewish question, his anti-communist views, his links to the fascist Sir Oswald Moseley and that he had fought in Spain for General Franco.

Nine months later in June 1943 he was escorted along with two other prisoners to a private villa in Kaun Strasse, in Zehlendorf, south west Berlin. The establishment was a prototype of the holiday camps that were to be introduced the following year where the Germans tried to identify potential recruits to the British Free Corps.

At Zehlendorf, Calthrop approached Dr. Hesse of the German Foreign Office, with a proposal that he be involved with the editing of films that the Germans were showing at POW camps, along with the English films that were coming through from the International YMCA. Dr. Hesse who it is said to be the last person to conduct negotiations with Britain on the eve of war, took him to the offices of the UFA film studios to meet officials.

Calthrop's stay at Zehlendorf was cut short when the camp was shut down prematurely because of the threat of increasing bombing raids on the capital. A new officers holiday camp opened the following year at Schloss Steinburg, near Straubing in Bavaria.

The camp inmates were evacuated en masse to Stalag IIIA at Luckenwald. Then Calthrop and others spent a short time at Stalag III-C at Küstrin before being sent to Oflag IX-A/Z at Rotenburg an der Fulda, near Kassel. Here he undertook the role of entertainments officer.

Undeterred Calthrop continued in his quest to return to Berlin and be part of the film industry and wrote to Dr. Hesse at the Foreign Office, reminding him of his earlier visit to Zehlendorf the previous year. His determination paid off and on 18 April 1944 Calthrop received a movement order that he was to be transferred to the other ranks holiday camp at Genshagen.

At Genshagen, Calthrop took a great interest in the camp theatre. After seeing Margery perform one of her shows he became besotted and pursued her at every opportunity. He admitted to being passionately in love with her and told Brown he would divorce his wife in order to marry Margery after the war.

Lt. John Calthrop, Margery and Dr. Ziegfeld of the German Foreign Office at Genshagen POW Camp © Trevor Beattie

In order to entrap Calthrop, Margery played along and pretended to fall in love with him. She provided tickets for him to watch her perform at the State Opera. They visited the Cafe Vaterland for meals and he visited her rehearsal rooms and even her flat, but always with an escort. She set the boundaries by telling him they mustn't compromise each other in any way. Telling him if he disclosed their affair she would not see him again.

In a blatant disregard of his orders, he exceeded his authority at the camp by having a series of interviews with various German officials. He had met with Dr. Arnold Ziegfeld, Dr. Hesse's superior at the English Section of the Foreign Office, both at Genshagen and at his private address at 9 Parade Platz in Tempelhof. Here he was informed of a project to make a film of POW camp life sponsored by the International YMCA in Sweden.

Sonderführer Meyer, the senior German at Genshagen escorted Calthrop to see Major Heimpel, the Kommandant of Stalag IIIA which had authority over Genshagen. They also travelled to the UFA Film Studios for an interview with Fritz Tietz, the editor of Deutsche Wochenschau (The German News Reel Film). Thomas Cooper took him for an interview with Herr Seeburg the editor of 'The Camp' newspaper and a member of the England Committee at his flat in the Wilmersdorf district of the city.

He was issued with an Ausweis signed on Himmler's behalf, allowing him to go anywhere within Greater Berlin in civilian clothes accompanied by a German escort. He also had unrestricted access to the camp telephone, ostensibly to call Dr. Ziegfeld, the Swiss Protecting Powers or the International YMCA organisation, but he used it for other purposes as well. In Berlin he met the traitor John Amery.

In July the Germans sent Calthrop back to Rotenburg. There he gave a lecture to 400 officers describing his time at Genshagen. Afterwards he received criticism and threats from some prisoners for his pro German views. One Prisoner said he felt nauseated by what he had heard. From Rotenburg Calthrop went to Stalag IX-A/H at Spangenberg to give a talk to the two camps there. At Spangenberg Upper Camp he was refused permission by the Senior British Officer Colonel Miller. Not least because the camp contained Major General Victor Fortune who had commanded the 51st Highland Brigade. He was the most senior British officer held as a POW by the Germans. The next day however Calthrop was able to give a lecture to 200 officers at Spangenberg Lower Camp.

Calthrop returned to Berlin where he hoped to further his plans to be involved in film production and renew his association with Margery. Instead of resuming his role at Genshagen he was sent to the main camp at Stalag IIIA in Berlin. Here Major Heimpel who did not trust him, had him arrested for travelling without an escort and arranged for him to be returned to Spangenberg.

Not wanting the other officers to know of his presence at Spangenberg he feigned illness and arranged with the German Kommandant to be put in a German civilian hospital outside the camp. After a month in the hospital he was visited by 63 year old Dr. Vivian Stranders of the Waffen SS.

Stranders was candid in his conversation with Calthrop, revealing that he was British born and was an intelligence officer in the Royal Flying Corps during World War One, holding the rank of Captain. He had been arrested in France in 1926 for industrial espionage on behalf of Germany and was sentenced to two years imprisonment.

He emigrated to Germany in 1928, joined the Nazi Party in 1932 and took German citizenship in 1933. During the Second World War he became a SS officer specialising in propaganda and working with British POW's. He was member of the Anglo-German Fellowship and didn't believe that the formation of the British Free Corps was the way forward.

He boasted that he was a personal friend of Hitler whom he had first met in 1931 and that he had recently been appointed to the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) headquarters as an expert on the United Kingdom, with the rank of SS-Sturmbannführer (equivalent to Major). In this role he had been ordered to investigate the progress the British Free Corps, (as John Brown was soon to find out to his cost).

On 23 August Calthrop was transferred to Oflag 79 at Brunswick, near Hanover, again taking on the role of entertainments officer. His Senior British Officer at Oflag 79 Lt. Colonel W.D.E Brown of the Royal Artillery sent word to MI9 in London on 17 November 1944. warning that Calthrop was a suspicious character. MI9 asked MI5 to investigate his background prior to his military service.

Calthrop was born 28 March 1914 in St. Pancras, London. He was to take to the stage like his father, film actor Donald Calthrop. In November 1932 he became engaged to Miss Joan Cassels Ford, the daughter of Sir Patrick Ford, Conservative MP for Edinburgh North. The pair were working together in theatre production at the Grafton Theatre in Tottenham Court Road. Miss Ford was Chairman of Vadis Production who were leasing the Grafton.

The following year and before their marriage Joan gave birth to their son Michael. The couple eventually married in 1934 at the British Consulate in Madeira. Prior to the war they were living at 29 St. Peter's Square in Hammersmith. His wife was now living at 20A Queens Gate Mews in Kensington.

Of special interest to MI5 was the discovery that he was a personal friend of Sir Oswald Moseley, the founder of the British Union of Fascists and had assisted him during his 1931 general election campaign. The matter was raised with the Under Secretary for War in Whitehall as Calthrop claimed to be working for British military intelligence.

In December 1944, MI5 sent a circular to the senior officers at all the Passenger Ports to be on the lookout for Lieutenant John Calthrop, POW number 759, who was suspected of collaborating with the enemy. He was to be detained and sent to No. 90 Reception Centre at Chalfont St. Giles in Buckinghamshire.

In early 1945, still harbouring ambitions to return to Berlin Calthrop wrote to Zeigfeld at the Foreign Office for assistance but the reply back wasn't very encouraging. Finally he wrote to Dr. Stranders seeking an interview. A few days later he received a visit from an English speaking Unteroffizier named Koss. He had brought a message from Stranders saying that if Calthrop would co-operate he would be granted his unconditional freedom and they could discuss furthering his film project.

It was proposed that Calthrop be returned to England to arrange for the immediate release of 500 British officers as a good will gesture. However following the bombing of Dresden by the Allies between 13-15 February, which resulted in the death of 25,000 civilians the plan was vetoed by Hitler.

He was also asked to write letters to his father in law Baronet Sir Patrick Ford, now an ex-MP, and other prominent people in an endeavour to get a question asked in the House of Commons as to whether the British Government approved of the maltreatment and rape of German women by their Russian Allies. (It is not known if these letters were sent, in his statement after the war Calthrop states that he told Koss he would think about it).

However four days later Calthrop received orders to leave at a hours' notice. He says that before he left he took the precaution of giving Lt. Colonel Brown the Senior British Officer two channels of contact through which he could be contacted. firstly through the waiter Jimmie at the Haus Vaterland, any messenger was to ask for the gentleman who buys roses. Secondly through Margery Booth, addressed to 'Die Rosenkavalier', (The Rose Bearer, a comic opera by Richard Strauss).

On 24 March 1945 Unteroffizier Koss duly arrived and escorted him to the HQ of Amptsgruppe 'D' at Fehbelliner Platz in Berlin. There Dr. Stranders informed him that he was the head of the British Free Corps, but he had now ceased recruiting members. Since the previous month he had been working on 'Operation Koniggratz', a propaganda campaign aimed at British prisoners of war, based at Kirchhain near Kottbus where there were 64 British other ranks.

Stranders took Calthrop to see a top Nazi official, SS-Obergruppenführer und General der Waffen SS, Gottlob Berger at his HQ in Douglas Strasse. Gottlob was now in charge of all POW camps in Germany. The General suggested that he take charge of a new scheme for the distribution of Red Cross parcels from Lübeck where they were to be distributed in Swedish lorries with British POW drivers. Calthrop accepted the offer subject to Red Cross approval. He also wrote to Colonel Brown at Brunswick informing him of his intentions. He was unaware that Heinrich Himmler, the Chief of the SS had set up his HQ at Lübeck, from where he had contacted Count Folke Bernadotte from Sweden and started negotiations for the German surrender with the West.

Calthrop was moved to Berger's personal HQ in Kinderplatz, under the care of his Aide de Camp, Oberfuhrer Jacobssen who had been involved in forming the SS Division Viking. After a few days he was informed by Berger that the Lübeck plan had been abandoned owing to difficulties in obtaining a special pass from the Red Cross.

Calthrop was given a temporary Ausweis to go into the city with an escort, but said it was possible to venture out on his own. Which he did on a couple of occasions to seek Margery but she had already fled Berlin.

By now Germany was collapsing fast, the Russians were closing in on Berlin, and the top Nazis were making plans to flee the capital. Calthrop had mentioned to Berger that he had political ambitions so it was suggested that Calthrop return to England, stand as a Member of Parliament and warn his compatriots about the danger of Bolshevism and the need to be lenient towards Germany post war.

Calthrop agreed to this so they came up with a plan. He was to be supplied with false papers and the cover story that he was a Hungarian electrician contracted to carry out electrical work on the railway network on the Swiss border.

Arrangements were made through Brigadefuhrer Schwellenberg, chief of the Waffen SS Secret Service. Dressed in civilian clothes and carrying a special Ausweis he left Berlin by train on 3 April 1945 bound for Munich, accompanied by SS Sturmführer Rutger von Gossler.

At Munich they reported to Sturmführer Dauser. Whilst the final arrangements were made with the Frontier Police for the crossing they stayed overnight with friends of Gossler in Prien. The next morning they travelled from Munich to Bregenz in Austria on the shores of Lake Constance, a train journey of 95 miles, and reported to the Wehrmacht Colonel in charge. Initially he refused permission for Calthrop to cross the border but after Gossler threatened to report him to SS General Berger he soon changed his mind. Gossler then left Calthrop to continue his journey alone.

On 12 April Calthrop left Bregenz for the five mile journey to Lustenau on the Swiss border. He had been told to meet Hauptmann Süss of the frontier guard by the third tree along in the avenue outside Lustenau railway station and declare himself as the 'the man from Berlin'.

Süss took him to a railway bridge on the border half a mile away and told him to run across as a train was passing. On the other side in St. Margarethen he was arrested by Swiss border guards. Calthrop then contacted the British Legation in Bern and gave a report of his escape from Germany.

Arrest

In the autumn of 1944 Brown had informed London of a Mercedes Benz factory six miles away from Genshagen in the Marienfeld district that was manufacturing Mk III Panzer tanks. The plant was bombed on 6 October but stray bombs fell on the camp badly damaging it. The permanent staff were sent to temporary accommodation while repairs were carried out.

Shortly after the raid Brown was arrested and confronted by Major Heimpel of the Abwehr and two members of the Gestapo. They had a statement from a British traitor by the name of Walter Purdy giving details of Browns espionage activities.

Walter Purdy was born 7 May 1918 at 270 Boundary Road in Barking, Essex. Before the Second World War Purdy, who had been an active member of the Fascist Party became a Merchant Navy officer. When hostilities started he was transferred to an armed merchant vessel, HMS Vandyke as ship’s engineer.

On 10 June 1940 the Vandyke was bombed and sunk off Narvik in Norway. After 36 hours in a lifeboat he was captured and became a PoW. In 1943 whilst in Marlag-Milag Nord PoW camp near Bremen he decided to defect and work for the Germans. They used him by sending him to different camps to spy on his fellow POW’s under the assumed name of Bob Poynter.

The Germans had placed Purdy in Colditz Castle as a spy. Here Captain Julius Green the Jewish dentist who Brown had met at Blechhammer, inadvertently informed Purdy of Browns role as a spy at Genshagen. The indiscretion also led to the discovery of a tunnel and a hide for contraband in the castle.

Brown denied the accusations and blamed it on some of the Jewish inmates, saying they were out to destroy the idea of a British Free Corps. With reservations the Germans believed him and released him, but Brown now knew that his time was running out. It would have cost him his life if the Germans had believed Purdy's story that he was a spy. Margery Booth would have been implicated as well with dire consequences.

With the Gestapo now suspicious of him Brown taught his secret code to Reg Beattie, one of his staff just in case he was re-arrested. He also passed over secret documents to Margery for safekeeping, these included a list of names of Allied soldiers who had defected and joined the British Free Corps. She said in a later interview that she never let the papers out of her sight and during her performances she hid them in her underclothing. This led to her being called the 'Knicker Spy' by some after the war.

During the war, Crown Prince Wilhem who had befriended Margery at Bayreuth, lived at Schloss Cecilienhof in Potsdam, 17 miles to the south west of Berlin. After the failed assassination plot on Hitler on 20 July 1944 the Gestapo had the Prince put under surveillance. Despite this Margery managed to bury the documents given to her by Brown in the grounds of his palace at Potsdam.

In October 1944 Hitler passed over the responsibility of the POW camps to the Waffen SS. Unaware of the holiday camps up to then they started an investigation into the activities at Genshagen. In December the camp was shut down and Brown and his staff were arrested by the Gestapo. They wanted to know why there were so many well targeted bombing raids at strategic locations around the camp and why the recruitment into the British Free Corps had been such a failure.

This of course was thanks to the efforts of Brown and his staff who had dissuaded British and Dominion troops from going over to the German side. At no time did it reach more than thirty in strength. A small number of men also joined the staff of the Ministry of Propaganda, working for radio stations and magazines. Brown and his staff were kept in a Strafe (punishment) prison for three weeks under interrogation. They were eventually released in mid-January 1945 and returned to Stalag VIII-B at Lamsdorf.

The Great March West

By the start of 1945 the tide of war on the eastern front had turned for the Wehrmacht. On 12 January the Red Army launched an offensive that would see them advance from the River Vistula on the Polish border to the River Oder on the German border.

The German authorities began evacuating the occupants of all nationalities from the POW and slave labour camps in the east to prevent them being liberated by the advancing Soviet Army. This became known amongst other names as 'The Great March West'. There were three main routes, the northern route, ending up at Fallingbostel in northern Germany. The central route to Luckenwalde, south of Berlin, and the southern route which led through Czechoslovakia to Nuremberg and Moosburg in Bavaria.

By 17 January, Warsaw the Polish capital had fallen and the Russian 4th Guards Tank Army were just 75 miles from Stalag VIII-B at Lamsdorf. Brown and his men arrived in Lamsdorf just in time to take part in the evacuation. On 22 January in one of the coldest winters of the century the first column of 1,000 prisoners left the camp to undertake the long trek back to Germany.

Some were in their fifth year of captivity and the malnourished and unfit men were in no condition to undertake such an arduous journey. They struggled each day through blizzards, relying on the meagre rations supplied by their German guards once their red cross supplies had run out. At night they crowded into barns or whatever shelter they could find. The unlucky ones huddled together in the open in freezing temperatures of -20 degrees.

The mortality rate on the march was high, (later it was compared to the Bataan Death March inflicted on American and Filipino soldiers by the Japanese Army in 1942). Many of the sick and weak succumbed to the conditions, and there were instances of stragglers being shot by the German guards. Another deadly hazard was the marauding Russian aircraft which attacked the POW columns believing they were retreating German troops.

Eventually after many weeks, Brown's column reached Bavaria, he and Jimmy Newcombe found themselves in Stalag 383 at Hohenfels just north of Regensburg. It was known to be one of the better camps with good facilities because it had originally been built to be an officers camp, Oflag III C. It was then designated a special camp solely for NCO's who were exempt from work details because of their rank. However over the winter of 1944/45 the prisoner population of 4,000 swelled to over 6,000 owing to the influx of POW's from the camps in eastern Europe.

By the Spring of 1945 the Americans were advancing ever closer, so on 17 April the Germans evacuated the camp leaving behind the sick and injured under the care of medical staff. The prisoners were marched south east via Regensburg and Petzkofen in the direction of Austria. After 60 miles the column was intercepted and liberated in the area of Frontenhausen by units of General Patton's 3rd Army.

To avoid being marched away by their captors to an unknown fate, Brown and Newcombe decided to hide in the camp along with the sick to await the arrival of the Americans. The camp was finally liberated on 24 April by the 51st Armoured Infantry Battalion from the US 4th Infantry Division.

Along with other released POW's Brown and Newcombe were flown to Brussels, the location of the British 21st Army Group Headquarters. On 4 May 1945, the same day that Field Marshal Montgomery accepted the German surrender on Lüneburg Heath near Hamburg, Brown completed a standard questionnaire form that all returning POW's submitted. Instead of being welcomed back and thanked for his contribution to the war effort he was promptly arrested by the Military Police as his name was on a list of suspected collaborators compiled by other repatriated prisoners.

He was placed under open arrest under the supervision of an escort until his story could be corroborated. After some communication between Brussels and MI5 in London he was visited by an officer from SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) who arranged his release.

He was then flown back to England in a RAF plane for a full debrief by MI5 before returning home to his wife Nancy and daughter Marion in Sunbury on Thames, Surrey. Ironically during the war Kempton Park racecourse, a hundred yards from Browns front door was used as a German and Italian POW transit camp, before their transfer to permanent camps.

Fleeing Berlin

In January 1945 Margery was arrested at her flat on suspicion of spying and taken to the Reich Security Main Office headquarters in Prinz-Albrecht Strasse, the headquarters for the SS, Einsatzgruppen, and Gestapo. Here she was held for three days under intense interrogation. She denied any involvement with Brown’s activities and with her captors unable to prove a case against her she was released.

The infamous Gestapo Headquarters in Prinz-Albrecht Strasse, Berlin

Margery was put under surveillance and had to report to Gestapo Headquarters twice a month where she was questioned for two hours at a time. Here she was put under enormous pressure to divulge information and threatened with deportation to a concentration camp.

The single largest raid on Berlin involving over 1,300 U.S bombers occurred on 18 March and resulted in thousands of civilian casualties. Margery later recalled having to soak her raincoat with water before venturing out because of the intense heat.

During another air raid towards the end of the month she fled Berlin with her friend Augusta, who had been her faithful maid of 15 years. They escaped just in time, by 14 April the Russians had encircled Berlin, and by the time the city fell over three quarters of it had been destroyed by Allied bombing and Russian artillery fire.

The pair travelled 145 miles south and made contact with the Americans in the town of Pössneck in Thuringia which U.S troops had captured on 13 April. They were then transferred a further 25 miles to a displaced persons camp at Naila, a small town to the West of Hof in Bavaria.