The Great Wigan Coal Robbery

Introduction

The following is the tale of an incident of alleged larceny that happened in, or rather under Wigan town centre 177 years ago, during the early years of the reign of Queen Victoria. The event which centered around the year 1848 caused much concern in the town and interest from further afield.

The court case that followed was covered extensively by newspaper reports around the country, the study of which points the finger of blame conclusively at the alleged perpetrator. However research of the court case records and prison registers held at the National Archives paints a different story. One that casts grave doubts on the verdict of the ensuing trial and points the finger of blame in another direction. It begs the question, was this a miscarriage of justice?

King Coal

Owing to its location in the centre of the South Lancashire coalfield it is no exaggeration to say that Wigan is built on coal. With the development of firstly the canals, then the railways, Wigan’s coal mining industry built up a reputation that was vital in helping to power the industrial revolution.

To satisfy the great demand for coal in the cotton mills and factories and on the railways it is estimated that in the 1840’s there were over a thousand pit shafts within a four mile radius of Wigan town centre. Also there are many old, abandoned workings that are not recorded. Many deep vertical shafts were sunk at various depths by the larger coal companies to intercept the rich coal seams, but around the built up town centre the extraction of coal took place from shallow surface workings and drift mines.

Chapel Colliery Pit

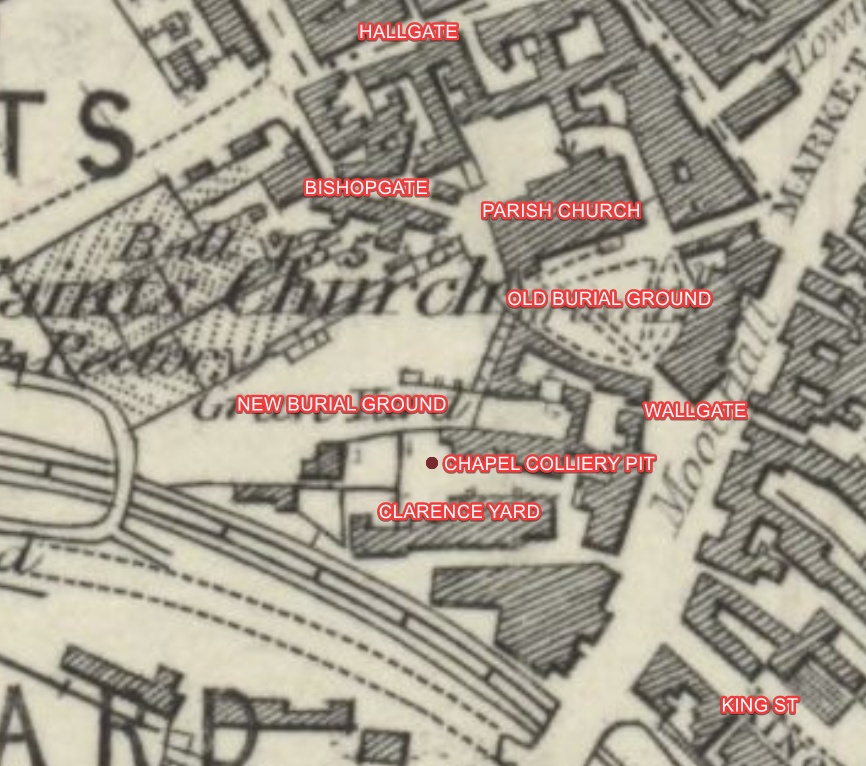

One such small mine, known as the Chapel Colliery Pit, was located in a yard behind the Clarence Hotel in Wallgate. Adjacent to the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel and close to Wigan Parish Church it was run by the Messrs Bleasdale Colliery Company.

OS 6" Map 1849 - Location of Chapel Colliery Pit, Wallgate, Wigan

John Bleasdale the proprietor of the company was born 14 January 1795 in Ashton in Makerfield, son of coal proprietor Henry Bleasdale. A widower, John married widow Catherine Cook on 18 May 1838 in Wigan Parish church. The couple first lived with Catherine’s children in Three Lane Ends in Hindley, before moving to nearby 12 Chapel Green.

Here Bleasdale carried out mining operations close to his home on two closures of land he rented, the ‘Big Chapel Field’ and the ‘Little Chapel Field’, to the east of Hindley Chapel (later named All Saints CE church). The land was part of the 57 acre Castle Hill Estate owned by John Grime, a farmer and also the registrar of births and deaths. Bleasdale also worked a pit at Water Heyes in Scholes in Wigan town centre. This enterprise was dominated by the three larger pits at Water Heyes operated by the Wigan Coal & Iron Company. As well as a coal proprietor he was also a master brick maker using clay on land he leased near his home in Hindley.

In late 1842 he employed a dozen men and boys as hewers and drawers to commence work on the Chapel Colliery pit, The underlooker or steward was William Golding whose responsibilities included inspecting the mine for safety and efficiency, ensuring compliance with regulations, and overseeing the daily operations of the underground workings.

A modern day view into the Clarence Yard from King Street West

Below ground was a seam of the highly prized cannel coal which was associated with the Haigh Hall estate of James Lindsay, the 7th Earl of Balcarres, where its mining was a significant part of the local economy.

(The name ‘cannel’ is corrupted from the word candle. Its high gas content made it an excellent fuel for early forms of gas lighting as it had the ability to burn as bright as a candle).

In early 1843 there was a fire in the mine caused by the negligence of the underlooker William Golding, resulting in the mine having to be sealed for many days to allow the fire to burn itself out. Expecting his services to be dispensed with, Golding left of his own accord. He was replaced as underlooker by a man named Enoch Grimshaw.

On 29 December the Wigan Coroner Mr. Grimshaw held an inquest at the Horse and Jockey public house in Scholes to investigate a fatal accident that had occurred at John's Water Hey Pit. Daniel Kelly, a shot firer was ramming explosive in a hole when his rammer caught on the side of the hole causing a spark which ignited the powder. He was badly burnt, surviving until Tuesday 26 December when death put an end to his suffering.

The Mines and Collieries Act of 1842 prohibited the employment of women, and also girls and boys under the age of ten to work underground in coal mines. This led to the rise of the ‘pit brow lasses’ who worked on the surface sorting coal from dirt on the coal screens. They were to become an important and vital part of the colliery work force. However the single inspector employed to police the act recorded that around 200 women were still being employed underground in the Wigan area, this was profitable to the mine owners as women were paid significantly less than men.

On 7 February 1844 John Bleasdale was summoned before Wigan Magistrates, John Lord (Mayor of Wigan) and Samuel McClure for employing two females underground at the Chapel Colliery pit. For his company’s illegal practice he was fined ten pounds, five pounds for each offence. Then the following month he was again fined £5 for employing a female underground worker by the name of Rebecca Melling at the same pit.

Even after the 1842 Act women were still being killed underground. A coroner’s report of 1844 stated that two Wigan women, 21 year old Jane Gore, and Ann Lawson aged 22, died underground in mining accidents. The dangers and the very real risk of injury or death were constant companions to miners and their families in the 19th century.

On 17 August 1844 an article in the Guardian newspaper reported that a few days earlier an explosion had occurred in the early hours of the morning at the Chapel Colliery Pit, caused by fire damp (an accumulation of the highly inflammable gas methane). Fortunately no one was working in the mine at the time.

Flames shot sixty feet into the air above the mouth of the pit, followed by a dense cloud of thick smoke. The greater part of the headgear was torn apart, damaging the weighing machine office and piercing a hole in the roof of the nearby Wesleyan Chapel. The debris carried a considerable distance, landing in the yard of the Buck I’th Vine public house, 300 yards away in Clayton Street. A second explosion occurred at 9.30 am, followed by several others in the course of the morning. Eventually the mouth of the pit was sealed off and the fire was allowed to burn itself out after several days.

In November 1844 John Bleasdale’s nephew Henry Bleasdale commenced working at the Chapel Colliery pit. He was employed as the ‘tallyman’ on the surface and also acted as book keeper, overseeing the men’s wages. (A tallyman kept a record of the coal being brought to the surface and was responsible for a safety check where miners would hand in a personal metal token (or tally) before a shift began to ensure all workers were accounted for. It was a critical safety measure to know how many colliers were in the mine in case of an accident or emergency).

Coal Robbery

The year 1847 was to be an eventful one for John. At the end of January miners at his Water Heyes Colliery went on strike after finding out that men working at the Wallgate pit were being paid one shilling and six pence a day more. Sometime previously John had purchased the mines underneath the property next to the Chapel Pit in the Clarence Yard. In order to gain access to this property he had purchased a lease from the Earl of Balcarres to enable him to drive a tunnel through his Lordships property. In this lease there was a reserved right for his Lordship’s surveyors to descend the Chapel Colliery in order to inspect the workings.

On 13 December 1847 Mr. John Tarbuck, his Lordship’s mineral surveyor was sent down the Chapel pit on the first of several visits to inspect the workings. He ascertained that coal and cannel had been gotten to a considerable extent beyond the legal boundaries. Also a drift had been driven under the churchyard and a part of the Parish Church.

His findings led to a warrant being issued for the arrest of John Bleasdale, his nephew Henry Bleasdale, and underlooker Enoch Grimshaw for having extended the workings of the coal mine beyond the limits of his property and stealing coal from adjoining mines.

When it became known to miners at the pit that proceedings had been brought against the three men they removed the ropes from the pithead pulleys, dismantled the engine and blocked up the air vents to the mine. They intimidated Mr. Tarbuck and his team and threatened to throw them down the pit shaft. Solicitor Mr. Mayhew acting on behalf of the Earl of Balcarres applied to the court for police protection while the surveyors carried out further investigation.

John Bleasdale absconded without trace, resulting in notices signed by Mr. Mayhew offering a reward of £10 for information leading to his arrest being placed in newspapers and on placards exhibited round town. The next day the reward was increased to £100.

The detailed reward notice described Bleasdale as ‘being about 52 years of age, about five feet eleven high, dark complexion, dark hair (but now rather grey from age), large eyebrows (same colour) and small grey whiskers cut short, when walking he has a peculiar and heavy gait inclined to a halt, stoops a little, has a small wart on his face near the cheek bone, cheeks rather forward, prominent eyes and large lips, usually dressed in a suit of black with white neckerchief and sometimes wears a brown cloth overcoat’. The rumour round town was that he had escaped by way of Fleetwood to Belfast and was now on passage to America.

Court Case

Henry and Enoch were both apprehended and on Friday 14 January 1848 were brought before the Magistrates at Wigan Town Hall for initial examination. The pair who were undefended faced three indictments brought by the Lord of the Manor Rector Gunning, the Earl of Balcarres and Revd. Benjamin Powell. They were charged with stealing a quantity of coal belonging to other parties, a large portion of that removed was from under Wigan Parish Church. John Bleasdale’s licence to mine in Wallgate placed restrictions on how deep and in what direction he could excavate, one of which was that he could only dig for thirteen yards in the direction of the Parish church boundary wall.

In opening the case Mr. Mayhew, on behalf of the Earl of Balcarres said that he should be able to prove that such a wholesale of plunder practiced by John Bleasdale was perhaps never before heard of; that mines belonging to twenty or thirty other persons had been pillaged, and that public buildings and streets had been undermined to an alarming extent. Despite donating to mining disaster funds and sitting on juries at the town hall as a seemingly upstanding member of the business community, John was now a wanted man for crimes against the town.

John Tarbuck, mineral surveyor gave evidence that at first Henry Bleasdale had refused him permission to go down the pit but on gaining entry had questioned about the many drifts that were closed up, he was told that they only extended six or seven yards. On eventually opening them up and examining them he found them to extend for more than a hundred yards.

Mr. Mayhew asked for remand until the following week, to give the surveyors time to complete their examination and plans of the pits. The pair were remanded and bail for their appearance was refused.

The following Tuesday Henry and Enoch were again brought up for further examination at the town hall before the Mayor John Lord, S.M McClure Esq. and Thomas Morris Esq. This hearing was to last for a full seven hours. Mr. John Mayhew again appeared for the prosecution, Mr. Blair, Mr. Ralph Darlington, Mr. Caleb Hilton and Mr. Ralph Leigh were the legal representatives for the defence. Mr. Darlington requested that Grimshaw be allowed to sit during the proceedings as his health had suffered since his incarceration and he was being cared for by Dr. Dalgleish. After hearing from witnesses Mr. Mayhew asked for an adjournment until the following week in order that the survey of the workings be completed and detailed plans drawn up. The defendants were once again remanded.

Ralph Darlington, Enoch Grimshaw's Attorney. Mayor of Wigan 1849/1850

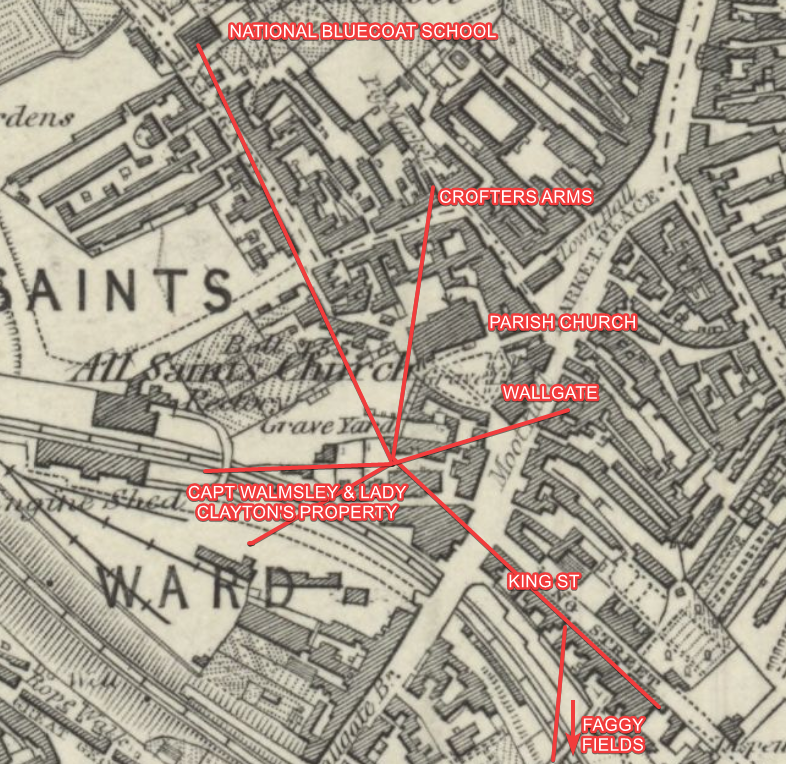

The case was resumed on Tuesday 25 January, the first witness called was surveyor John Tarbuck. He stated that six or seven drifts had still not been examined as they were completely filled with dirt. However the survey of the cannel workings were complete, extending to the property of Mr. Thomas Pemberton Leigh (later 1st Baron Kingsdown).

There were twenty nine drifts under Hallgate from where cannel coal had been extracted, and from under the National Bluecoats School. In his opinion the pillars were insufficient to support the weight, and some drifts under water had not yet been surveyed. He found that the extent of the drift under the churchyard to be about twelve yards further than he had first thought and went for 146 yards in a straight line. A drift opening out of the cannel in the Lower King Coal Seam on the north side of the pit went for 131 yards in a north east direction with at least sixteen minor drifts leading out of it. The drift which crossed under Lower Hallgate proceeded as far as the Crofters Arms bowling green.

Mr. Hedley, a mineral and land surveyor was examined next. He said he had surveyed the surface plan and confirmed that cannel had been extracted from the property belonging to Lord Balcarres, Rector Gunning, the churchwardens of Wigan Church and churchyard, the National Bluecoat School, the Wallgate Methodist Chapel, the Manchester & Southport Railway Company, Revd. Thomas Marsden, Thomas Morris Esq, the Rt. Hon Pemberton Leigh, the Revd. Benjamin Powell, and Lady Clayton.

In total he estimated that 1,200 tons of coal had been unlawfully taken from an area of 20,000 square yards (about 4 acres). The areas affected included Wallgate, Hallgate, Bishopgate, King Street and Faggy Fields. Under Hallgate cannel had been extracted for 140 lineal yards and in his opinion the street would ultimately sink. At least 220 cottages and other buildings had been undermined, many of which would have to be demolished.

OS 6" Map 1849 - showing the extent of mine workings from the Chapel Colliery Pit

The value of the coal got at between 11s. 8d and 12s. 3d per ton would be between £10,000 and £12,000. In addition a smaller amount of King Coal, worth about £800 had been extracted beyond the boundaries of Captain Walmsley’s and Lady Clayton’s properties. (King Coal refers to the ‘King Coal Seam’, known for being a rich, important seam in the Lancashire coalfield. It was mined extensively in the Wigan area and was known for the high quality coal it yielded).

Mr. Stott, surveyor to Mr. Walmesley was examined and stated that no authority had been given to Bleasdale to get the coal from under or within a distance of forty yards of the house occupied by Mr. Charles Pigot Esq, an attorney and coal proprietor in Bishopgate.

Mr. John Brimelow, assistant to Mr. Mort, a surveyor of Tyldesley was examined at great length. He had surveyed the workings on several occasions, the first time in 1846 but had only gone through part of the pit. He saw a tunnel but did not enter as he had only gone down to survey the portion leased by Lady Clayton whose mines lay to the southwest of the pit eye. He stated that his next visit was in November 1847, by this time Enoch Grimshaw had left and was now employed as underlooker at the Strangeways Pit in Hindley. He was escorted by William Pollard the underlooker at the Birkett Bank Pit, Henry Bleasdale, and a miner named Livesey. They assisted him in surveying the workings by a method known as dialling.

(Dialling is the use of a surveying instrument known as a miners dial, used for establishing directions and angles of underground roadways and tunnels, by measuring magnetic north and the inclination of mine shafts and tunnels).

John Brimelow then surveyed the tunnel that he had seen on his previous visit, as far as the National Bluecoats School. They had occasion to go along the King Coal level to the first cannel drift where the higher King Coal level strikes the Hallgate Croft at an angle. They did further dialling to the end of the lower King Coal level and also some cannel drifts on the right hand side of the tunnel. Some drifts were blocked off and when he inquired where they went he was told they went only as far as their boundaries. One drift extended northwards towards the National Bluecoat School but he was refused permission to enter. He was told that there was a danger of fire and explosion.

The trial continued on the Wednesday and the whole day was occupied in hearing further evidence. The first witness, on behalf of the Rector and the churchwardens was mine surveyor Mr. Robert Kellett, who himself lived in the affected area. He testified that the churchwardens had suspected Bleasdale of excavating beyond the church boundary and under the churchyard and had requested him to inspect the mine four years previously.

Although as the law stood he had no power to enter without the authority of the proprietor, he had gained entry. He testified that the underlooker at the time Enoch Grimshaw, had at first tried to prevent him going down the pit, saying that John Bleasdale would be very angry if he found out. After dialling he estimated that the drift was 182 yards from the pit shaft, had gone under the churchyard and was now under the property of Mr. Marsden. For reasons he could not explain no further action was taken at the time.

Next up were colliers Christopher Causey, William Causey, and John Pennington, who were examined to prove the prisoner’s connection to the felony. Then the Revd. Benjamin Powell, and Mr. Thomas Morris were questioned to show that coal had been taken which was not let or sold to John Bleasdale The prisoners were then further remanded to Thursday morning at 11am.

The next day Mr. Tarbuck the surveyor gave further evidence. He described how his investigations had been willfully obstructed by the removal of vital parts from the winding gear engine and the blocking up of air vents. At the end of proceedings the Court committed Henry and Enoch for trial at the Spring Assizes in Liverpool but reserved until the next day their decision whether to accept bail or not. On Friday, the fourth day, the bench decided that both prisoners were to be released on bail until the Spring quarterly sessions with the surety of £100 to be guaranteed by two responsible people each. John Green a bacon merchant from Wigan, and John Anderton of Hindley vouched for Henry, and for Enoch his employers at Strangeways Pit in Hindley, Mr. H. Taylor and Mr. T. Byrom.

The consequences of John Bleasdale's actions hit home when four warrants of distress were issued and heard before the Mayor at the town hall. Four colliers, by the names of Thomas Wood, William Wood, Enoch Moore and William Fish made claims against Bleasdale for unpaid wages totalling £5. 11s. 5d. the claims were proved and orders granted for their payment. The same day a summons against John for non-payments of gas and highway rates was lodged. Two weeks later colliers at his Water Heyes pit went on strike for better pay and conditions.

Spring Assizes

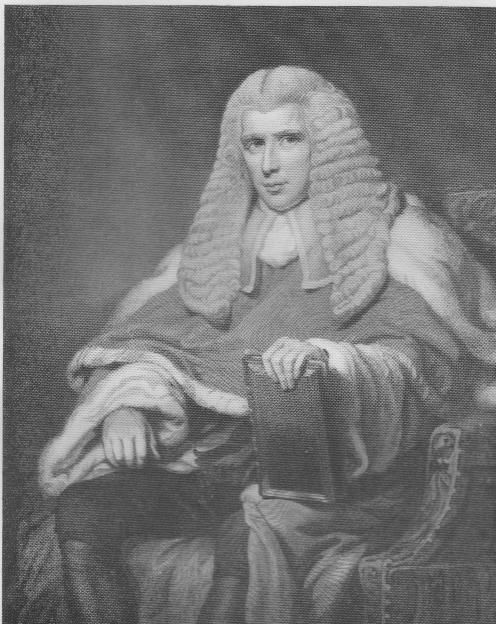

Enoch and Henry appeared before his Lordship Mr. Baron Alderson at Liverpool Crown Court on 3 April 1848. Mr. Pollock and Mr. Wheeler acted for the prosecution and Mr. Wilkins and Mr. James for the defence.

Crown Court Judge - Baron Sir Edward Hall Alderson

To the charges Henry pleaded not guilty but was found not have profited financially from the actions of his uncle so was acquitted of all charges. Enoch pleaded guilty to the charges. In Grimshaw's defence it was claimed that he hadn’t seen the deeds to the coal mine, only the plans, therefore didn’t know what arrangements had been made between his employer and other parties concerning the boundaries and limits of excavation. It was therefore accepted that he was only following the instructions of the mine owner John Bleasdale. Enoch was also found not guilty and acquitted.

Both men were bound over in their own recognizance’s of £500, in order that they return to be witnesses in the trial of John Bleasdale, should he be caught. (recognizance is a form of bail that relies on a promise to pay a specified sum if the conditions are breached, rather than a cash deposit upfront).

Six months after reports of the alleged felony taking place, the case still held the attention of the public and the press. It was reported in the Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser on Saturday 20 May 1848 that some of the owners of the coal mines in the neighbourhood of Scholes had received compensation for coals taken from their property by the Bleasdale Colliery Company.

An article in the Manchester Examiner dated 4 July 1848 stated that Mr. Hedley the land surveyor who had given evidence at the trial in Wigan had now reported that in several houses in Wallgate the walls were parting from each other and the beams giving away several inches. Also some of the pavements had sunk. It was his opinion that Wallgate would ‘sink into the hollows’.

On the 15th of July Gores District Advertiser reported the dissolution of the partnership between John Bleasdale and Jonathon Jowitt, his co-owner of the Birkett Bank Pit.

Two weeks later on 29 July the Preston Chronicle & Lancashire Advertiser reported that a macabre event had happened at Wigan Parish Church graveyard where large crowds had gathered at the lower parts of the burial ground. In the course of the previous week, excavators employed on the nearby Bury & Liverpool line had succeeded in partially cutting through between Bleasdale’s Clarence Yard pit and the walled boundary of the burial ground.

A large portion of the wall collapsed and exposed to public view the coffins of the dead along with their contents, some in skeletal state and some apparently newly shrouded. While the excavators dug up the coffins and their contents the sexton was busily employed in collecting up the small bones of the dead in a wisket (straw basket) which he deposited in the bone room at the church.

Brought to Justice

In December 1848 newspapers reported that on the evening of Friday 8 December John Bleasdale had been arrested in London. He was apprehended at Hungerford Market in the Strand, near Charing Cross by Detective Field of the London Metropolitan Police force who had been on his trail for a number of weeks. It was reported that John had sailed across to France by cargo ship instead of using conventional means of travel. He had then spent nearly a year on the continent, mainly in France, before returning to London in November 1848.

He was brought back to Wigan next morning on the mail train. On the Monday large crowds of people gathered at the police station expecting him to go before the Magistrates for examination. Instead at two o’clock he was taken to the railway station in Wallgate, there crowds gathered to catch a glimpse of him being conveyed to Kirkdale Prison in Liverpool.

On the suggestion of Mr. Ralph Leigh, a new attorney Mr Caleb Hilton of Wigan was employed to defend John, but as there was very little time to prepare a defence it was decided to apply to have the case postponed to the Spring Assizes. The request was denied and ten days later John appeared before Judge Erle at Liverpool Crown Court to answer the charges against him.

Crown Court Judge - Sir William Erle

Mr. Pollock and Mr. Wheeler conducted the case for the prosecution. Mr. Monk and Mr. James defended the prisoner. The case had already been thoroughly investigated the previous year, the financial cost of coal stolen, and of property damaged had been determined. Whereas Enoch and Henry had been charged with aiding and abetting the felony. The prosecution had to prove that John had not signed any contracts to purchase or lease any of the affected mines and had not been granted permission to mine under people’s property.

The laws concerning land ownership and general property rights were complex. Firstly was the ‘Presumption of Ownership’. The fundamental legal principle that a surface landowner owned everything from the surface down, including all minerals such as coal below their land, and all in the sky above. However this presumption could be challenged, landowners might have reserved the rights to the minerals when selling the surface land, or the ownership of minerals could have been altered by other legal means, this would be reflected in the ‘Title Deeds’ of the land. The right of landowners to exploit minerals under their land had been regulated by the 1842 Mining Act and further subsequent mining laws.

The prosecution stated that John Bleasdale had caused great harm, distress and financial hardship to the residents of the town by plundering coal and cannel belonging to other parties and dangerously undermining streets and property. Surveyors John Tarbuck, John Hedley, and John Tarbuck gave evidence for the prosecution along with Enoch Grimshaw.

After a two day trial the jury found John guilty of breaching Section 37, Chapter 29 of the Statutes passed in 1827 and 1828 in the reign of His Majesty King George IV relating to the prevention of encroachment of mines. Mr. Justice Erle sentenced him to transportation to the Penal Colonies for seven years. However a successful appeal was lodged and the sentence was commuted to just seven years imprisonment owing to the complexities of the case, many of which were still unresolved.

John was returned to Kirkdale Prison to serve his sentence. The House of Correction in Liverpool was a major facility in the mid 1800’s and was also used for public executions. Life was very hard for the inmates, characterized by solitary confinement, hard labour, high death rates, and harsh conditions, including forced work on the largest treadmill in the country used to grind corn or working on cotton weaving or other menial tasks.

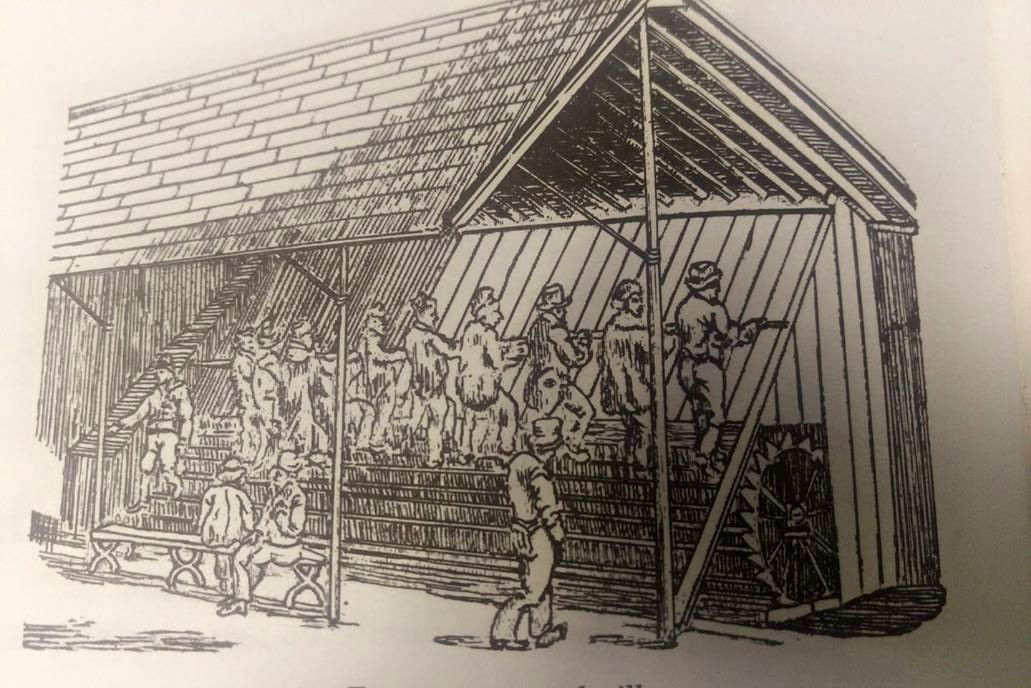

Kirkdale Prison treadmill - 1836

He relied on his friend, 45 year old Richard Martinscroft, a painter and guilder who lived in the Clarence Yard in Wallgate to act as his agent in dealing with his new solicitor George Dodds who had offices at 5 James Street in Liverpool. Dodds then corresponded with the authorities and a Mr. Horace Waddington, a legal secretary at the Home Office in London.

Back in Wigan the controversy over the scandal rumbled on. An article in the Preston Chronicle dated 3 March 1849 described that a meeting of Wigan Ratepayers presided over by Mr. Daniel Davies, had taken place at the Commercial Inn in the town centre. To cries of ‘Shame’ ‘Shame’, he disclosed that the treasurers account for the previous year showed that John Mayhew, one of the prosecutors in the Bleasdale and Grimshaw case had claimed £329. 9s. 4d (allowing for inflation, worth over £45,000 today), the other prosecutor Mr. Ackerley had claimed £315. 8s. 8d. This compared to just £33. 2s. 8d. (worth £5,000 today) paid to Mr. Ralph Leigh, prosecutor of Henry Abraham at the same assizes for burglary.

Appeal

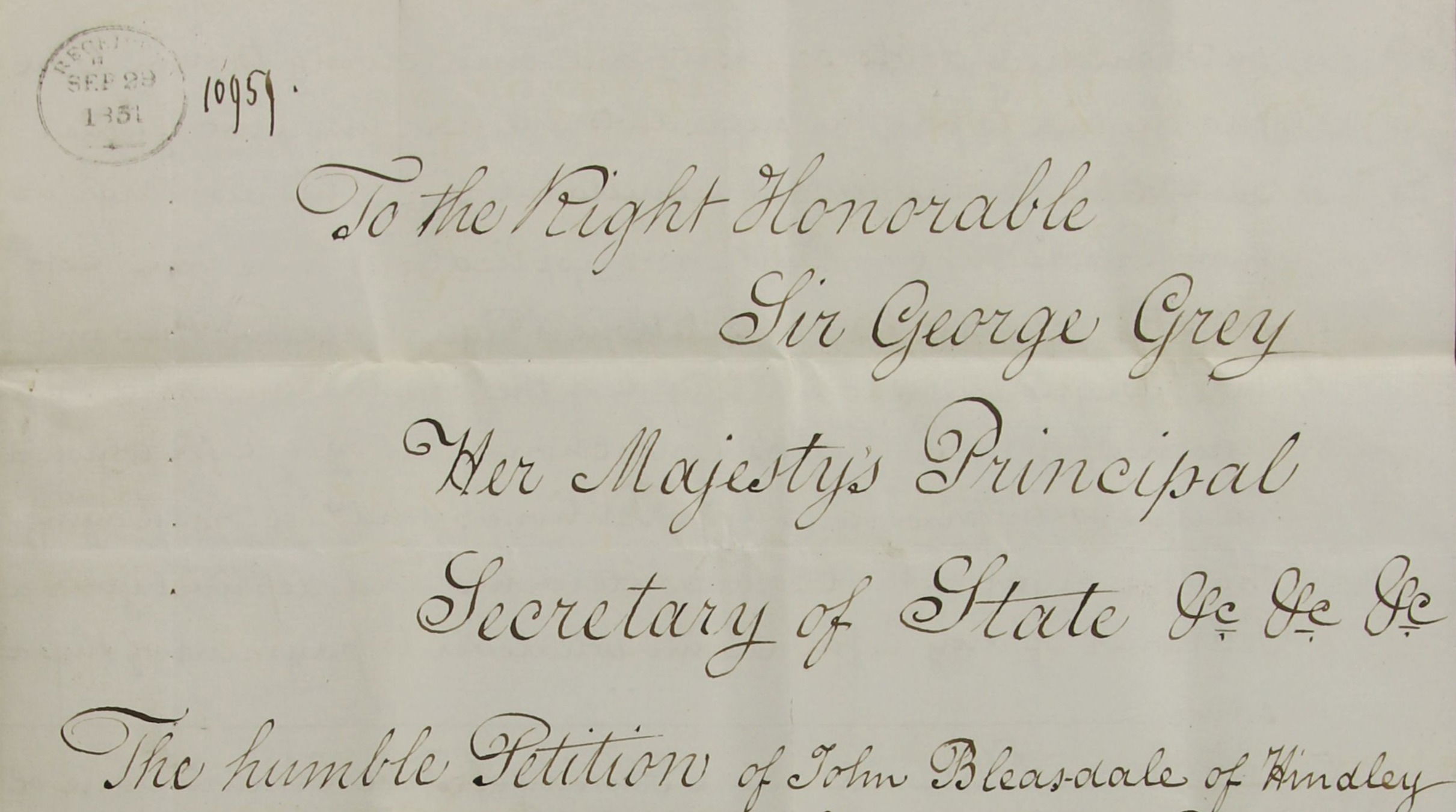

In July 1849, after being incarcerated in Kirkdale for seven months John finally got the chance to tell his story. On the 20th of that month he made an official appeal in a lengthy statement to the Rt. Hon. Sir George Grey, Her Majesty’s principal Secretary of State for the Home Department in Whitehall, asking for an inquiry into the circumstances of the case.

Sir George Grey - Home Secretary

He testified that when he had been apprehended the Winter Assizes were already in Session, therefore he hadn’t had enough time to prepare his defence. Also that he had effectively been tried in his absence at the trial of his two employees at the Spring Assizes

He related all the events that had happened since acquiring the lease of the Chapel Colliery Pit in 1842 and explained that the land leased from Mr. Walmsley in Wallgate was much intermixed with property belonging to other persons and the Chapel Colliery could not be worked to a good advantage unless in connection with some of the adjoining mines. He had therefore contracted with several parties for the purchase of their mines in order to avoid any difficulty with them as to trespass.

Following the fire at the pit in 1843 he had received a note from Mr. Peace, mining agent for the Earl of Balcarres, stating that he had been informed that John had been taking coals that belonged to His Lordship. He therefore wished to go down the Chapel Colliery pit to inspect the workings. John replied that he would only allow him if he disclosed the name of the informer. He was told that it was his former underlooker William Golding who had left his employ following the pit fire.

John had then sent two men down the pit to dial. They found that no trespass had occurred on his Lordships land but a drift had been cut across the corner of the new church burial ground. He contacted the churchwardens and offered to either pay compensation or replace the small amount of coal taken. He stated that he would purchase the whole of the mines under the churchyard if the church wardens felt so inclined.

He even made the same offer to Revd. Gunning the Rector, but nothing came of it. The following year the church wardens were changed. An application was then made by attorney Mr. Ackerley on behalf of the new church wardens for Mr. Kellet a surveyor to go down the pits to ascertain the amount of trespass under the church and the burial ground.

Afterwards he received from church warden Colin Lindsay (the brother of the Earl of Balcarres) an estimate of what the church claimed from the trespass. Finding this amount excessively high he remonstrated with the late churchwarden Mr. Feeley, but nothing more was heard on the matter. About the same time several owners on the south side of the pit had requested that surveyor Mr. James Johnson be allowed to examine the workings, this was granted but he found that all was right.

Following the explosion at the pit in August 1843 John testified that he was reluctant and fearful of going down the shaft. He therefore left the entire management of the underground workings to his underlooker Enoch Grimshaw.

In May 1845 Mr. Stott the agent for Mr. Walmsley informed him that something had gone wrong with the excavations carried out and that several drift bays were under the Hallgate Croft. He communicated this information to Enoch Grimshaw and ordered him to stop all work until he had agreed to purchase them or pay compensation. He contracted several parties to purchase these mines, amongst them he bought the Hall Gate Croft, consisting of about half an acre, from Mr. John Leyland. Also he concluded a similar purchase with Lord Balcarres. Enoch Grimshaw was informed of these arrangements.

In order to get the coal and cannel that lay below the level of the pit it became necessary to sink deeper and to cut a tunnel to communicate with the pit eye. He gave strict instructions to Enoch Grimshaw that because of the previous disputes the direction of the tunnel and cut should go through that part of the mine leased from Lord Balcarres and that he must be sure and keep clear of the church yard. Despite this warning Grimshaw of his own accord and unknown to John Bleasdale cut straight under the churchyard. When brought to account over this he said that they had only trespassed a few yards, He was ordered to start a new cut further back and keep a sufficient distance from the church yard.

By early 1846 the cannel miners had reached the boundaries and the work force was reduced from 29 or 30 to the nine or ten that work could be found for. That year the Water Heyes Pit became worked out so in April, along with a partner he had purchased the Birkett Bank Pit in Wigan, the management of which took up a lot of his time. Enoch Grimshaw was made underlooker of this new pit as well but allowed similar irregularities to be made as in the Chapel Colliery Pit. He treated them as mere trespasses which would be satisfactorily settled by compensation being made to the injured parties. This was the usual practice in the mining industry in the Wigan area and in his opinion if all such trespasses were treated as felonies not a single coal proprietor would escape.

Towards the end of 1846 he received notice from the Manchester and Southport Railway Company that they desired to purchase the Chapel Colliery pits and requested a statement of the amount required for compensation. To arrange the sale he obtained the plans of the pit from Enoch Grimshaw who now worked at the Strangeways Pit in order to ascertain how much coal and cannel remained unmined.

Previous to this request he had not been down the pit to examine the workings for over two years and had not seen the plans for a long time. He realised that Enoch Grimshaw had made considerable extra workings without his knowledge that were beyond the boundaries. He then made application to the different owners of property adjacent to Hallgate proposing to purchase their mines. Most of these agreed to sell on the terms offered.

He then took his surveyor Mr. Livesey along with him to the agent of Mr. Cardwell and offered to buy the whole of his mines in Wallgate or offer compensation. He was told that Cardwell was in London at that time but that he would write to him over the matter. He heard nothing in reply until 11 December 1847 when Mr. Peace, the agent for Lord Balcarres applied for permission to go down the mine to survey on behalf of Mr. Cardwell, this was granted. Despite having concluded agreements with some mine owners and was in talks with the remainder, Mr. Peace made overtures with them to join with him in a prosecution against John.

On 11 January 1848 Daniel Eccleston, one of John’s employees at the Chapel Colliery Pit and who lodged with Enoch Grimshaw, met him as he was arriving at the railway station and warned him that the police were searching for him. He then visited his attorney Mr. Ralph Leigh, who was also the legal advisor to the Magistrates of Wigan. He was advised by him to go away for a time to avoid the upcoming Wigan Sessions, as there was not enough time to prepare his defence. In the meantime he would see if matters could be settled with the aggrieved parties.

Concerned that such a course of action would be evidence of his guilt he strongly remonstrated but at length he reluctantly agreed through the persuasion of Mr. Leigh. At first he went to Stockport where he stayed for five months, there he was advised to go to Boulogne, so in May travelled down to Folkestone. In the end he changed his mind, he remained in Folkestone for six months and did not cross the channel to France. Whilst in Folkestone he sent numerous letters to his attorney Ralph Leigh asking for advice but did not receive any replies. In November, wanting to be nearer to home he travelled to the village of Horwich End, near Whaley Bridge in the High Peak District of Derbyshire.

There along with his nephew Thomas Gerrard who would act as witness, he arranged a meeting with Enoch Grimshaw to discuss all the events that had taken place since he became his underlooker in 1843. During the conversation Enoch asked John to pay part of his legal fees still owing to his attorney Ralph Darlington, he refused as it would be construed that the payment was a bribe. As a result of his meeting with Grimshaw he decided to go to London to seek legal advice. It was there the following month that he was arrested.

He was advised by Ralph Leigh to employ Mr. Caleb Hilton of Wigan to conduct the defence. But as there was so little time to prepare a case at short notice it was deemed advisable to get the trial postponed until the upcoming March Assizes. This request was refused and the trial had gone ahead. He was not present at the preliminary hearing before the Magistrates and did not know what offence he had been indicted for. Nor did he know how many witnesses there were against him until they were called into the box to be examined. He was altogether unprepared for any proper defence otherwise he would have provided evidence which would have completely refuted the statements of the principal witnesses for the prosecution.

He swore that Enoch Grimshaw had given evidence in court completely at variance with the one made at Horwich End in the presence of his nephew Thomas Gerrard. He deeply regretted having taken the advice of Mr. Ralph Leigh to leave his home and business and abscond from Wigan. That action had been construed as an admission of guilt by his enemies and damaged his reputation in the eyes of the world.

Along with his own application he submitted the sworn statements of six other persons who had knowledge of the alleged offences and the circumstances leading up to his arrest. These had been dictated and sworn in Liverpool before Master Scholar in Chancery, Mr. Monas Dodge.

The supporting statement by Henry Bleasdale emphasized that Enoch Grimshaw was in full control of the entire workings of coal and cannel in the colliery. That if the ‘dialings’ of surveyors John Tarbuck and John Hedley were correct then there were three distinct parts of the workings trespassed upon. This was the responsibility of Enoch Grimshaw who had acted contrary to the instructions and directions given by his employer. He (Henry Bleasdale) had heard his uncle specifically tell Grimshaw to keep away from the church yard.

He challenged the evidence given by John Tarbuck at the trial in that he had included several lots as being trespassed upon when in fact they had been purchased prior to mining. Also that the length of the drifts and the amount of coal taken had been exaggerated. Finally he stated that he had been present at the meeting between John Bleasdale and Ralph Leigh when the attorney had persuaded his uncle to go away for a while.

In his statement Thomas Gerrard, stated that he had been present at the meeting between his uncle and Enoch Grimshaw at Horwich End in November 1848.

He said that Grimshaw had admitted that if any workings were under the churchyard it was by mistake. That the galleries beyond the boundaries had been done in the supposition that it would make little difference as to when the cannel was got, as John Bleasdale intended to purchase all the coal and cannel in that vicinity. Also that he didn’t realise he was breaking the law by doing so. In his opinion the evidence that Grimshaw had given at the trial was contrary to the details that he had given to his uncle at the meeting.

He believed that what Grimshaw had said under oath at the Assizes was false in order to deflect the blame from him and implicate his uncle. He was present in court but had not been called as a witness by the defence counsel. If he had he would have been able to contradict Grimshaw.

In his sworn statement William Pollard aged 73, who had been employed as an underlooker at the Birkett Bank Pit said that in November 1847 he went down Chapel Colliery Pit with miners John Livesey and John Brimelow to examine the mine workings.

He stated that Enoch Grimshaw, with the help of an assistant by the name of William Ashton had the whole and sole management of the underground workings without the interference of John Bleasdale.

Also that he had attended the Spring Assizes and if he had been called as a witness he could have proved that several statements made by Grimshaw were untrue for the purpose of implicating his employer and clearing himself.

He stated that at the trial of John Bleasdale it was claimed that the value of the coal and cannel mined without permission was greatly exaggerated at £10,000. An eminent surveyor by the name of James Whittle employed to survey the damage estimated it as only £615. 15s 7d.

The character reference statements of miners John Wright, John Hart, and Samuel Smith were identical. They all testified that they had worked at the Chapel Colliery since it’s commencement in 1842. That John Bleasdale was a fair employer who had given advances on pay when needed, and that he didn’t interfere with the miners’ work, leaving the management of the workings underground to his underlooker Enoch Grimshaw.

As well as his statement John also enclosed a petition which was signed by 331 professional people and business owners from Wigan, Hindley and Westhoughton. The list vouching for the good character of John Bleasdale contained the names of a Catholic Priest, a surgeon, various Gentlemen, coal proprietors, farmers, grocers, butchers, drapers, shoemakers, and many more persons of various trades. The petition stated that: ‘John Bleasdale was always a sober, steady and persevering tradesman, endeavouring to the utmost of his power, according to his circumstances to promote not only his own but the interests of others, especially those of the working class, and was a very useful member in society and always borne the character of a religious man from his youth, and devoted much of his time to the instruction of the rising generation in the Methodist Sabbath schools’.

The Home Secretary noted that the application for an inquiry had come in rather late and asked his secretary Mr. Horace Waddington to request a report on the case. Waddington wrote to Judge Baron Alderson who replied that although it wasn’t him but Mr. Justice Erle who had tried John, he was still acquainted with the case as he had tried Enoch Grimshaw. In his opinion things were not favourable for John Bleasdale as he had absconded for a year and hadn’t stayed to prove his innocence.

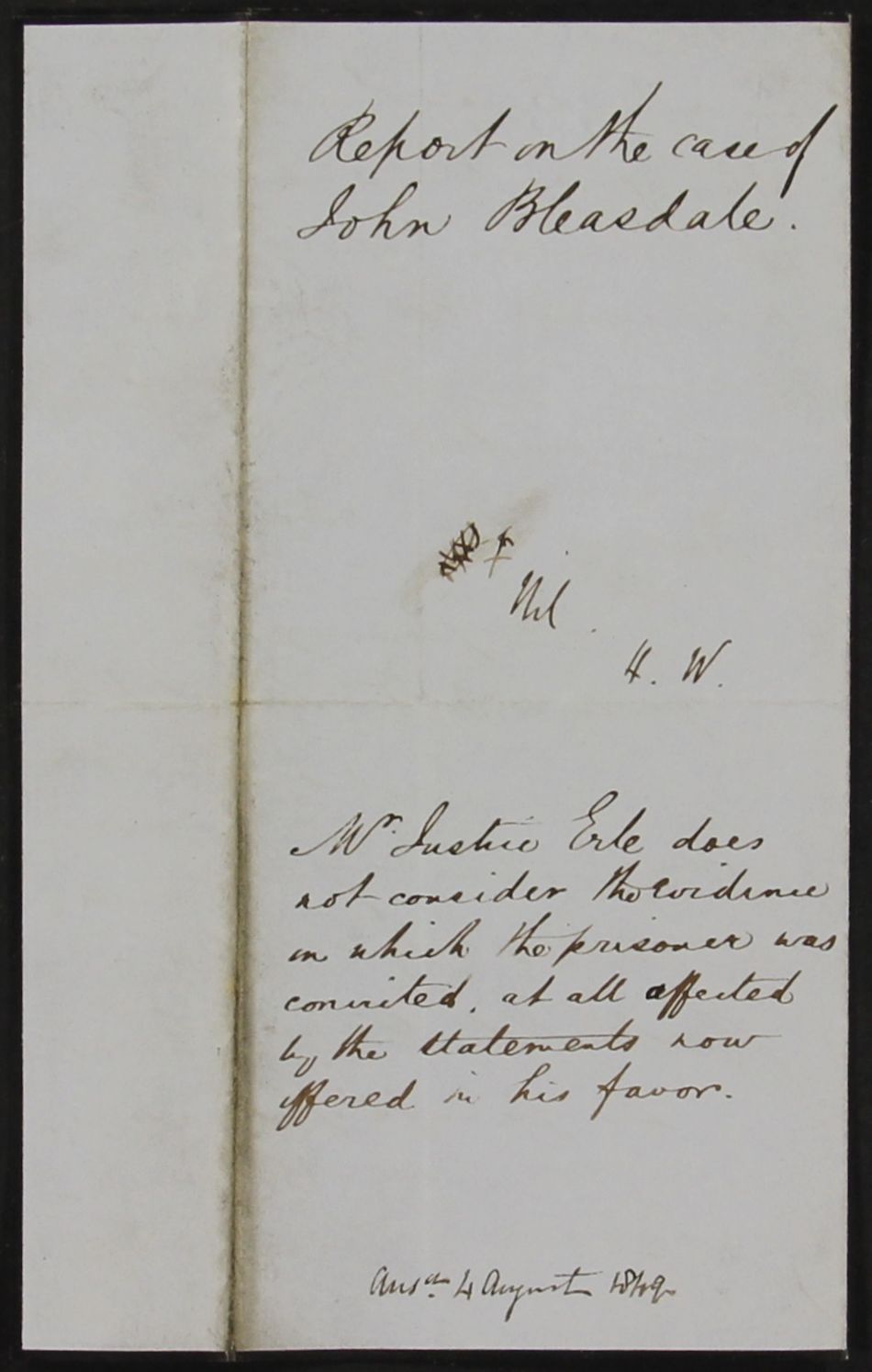

Mr. Justice Erle wrote a report for the Home Office in which it stated that in his opinion Bleasdale knew the direction of the workings was wrong and he knew he was stealing coal from other persons to benefit himself. In his opinion he did not consider the evidence on which the prisoner was convicted was at all affected by the statements now offered in his defence. As a result on the 4th of August the Home Secretary decreed that the plea for an inquiry was denied.

John Bleasdale's failed appeal to the Home Secretary of 4 August 1849

Second Appeal

On 13 October 1849 John was informed of plans to transfer him to Mill Bank Prison in Westminster, London. (a notorious institution that was a holding centre for convicts awaiting transportation). This prompted him to write to his solicitor George Dodds asking that he enter a plea on his behalf to the Home Secretary requesting that he remain at Kirkdale for a further six months, in order for his financial affairs to be finalised. Sir George Grey saw no objection and his request was granted.

Enoch Grimshaw was persuaded to make a declaration in support of his former employer which he signed on 18 June 1850. In his statement Enoch Grimshaw declared that he had been engaged by John Bleasdale at the Chapel Colliery pit in March 1843 to become steward and superintendent of the workings and getting of coal and cannel. (Interestingly the previous words in italics which confirmed that he had authority over mining operations been crossed out and countersigned by the scribe).

He stated that he had worked under the plans and instructions given by John Bleasdale, but that his employer was in total ignorance of any part of the proposed workings to be under any part of the church yard. Also that he disagreed with the findings of surveyors Kellett, Hedley and Tarbuck and at the trial they had grossly exaggerated the amount of damage done. He concluded that John Bleasdale was a good and fair employer and of good character.

Three months later on 18 September 1850 John wrote to his solicitor George Dodds from his prison cell in Kirkdale requesting him to make another appeal for clemency to the Home Secretary. He enclosed a covering letter written by himself that explained his struggle to reclaim debts owed to him and the injustices carried out against him.

Nine years previously in October 1842 he had leased the Chapel Colliery Pit in the Clarence Yard, Wallgate for a period of twenty one years at a fixed rent of £200 a year. It was on land owned by Captain John Walmesley, who resided in the city of Bath. In addition he paid £200 to mine on parts of the adjoining lands of Lady Clayton and others.

Shortly after the legal proceedings started Mr. Stott, Captain Walmsley’s mining agent took advantage of his absence. Under the pretence that he had breached the covenant of the deeds and therefore forfeited the minerals on Mr. Walmsley’s land he had taken forcible possession of the colliery, and had been working it ever since until it was worked out. Stott had since sold off the engine, tools and equipment for his own advantage. Just prior to this, following the bid from the railway company he (John Bleasdale) had valued the sale price of the Chapel Colliery at £4,500.

In 1845 he had agreed with Mr. Peace the mining agent for Lord Balcarres and the author of his prosecution, for a small lot of mines belonging to his Lordship near the Chapel Colliery and the churchyard. The lease was for ten years and he had paid £113 in advance. He now contested the amount of compensation for trespass levied by Mr. Peace as being excessive.

John had made frequent offers to John Roper, a brass founder who owned ten cottages in Higher Wallgate, to purchase the lease to mine under his properties which were adjacent to the Chapel Colliery Pit. The last time being on 30 December 1847 when he offered £120 per foot. He claimed he had made a verbal agreement with Mr. Walker the Rector’s steward to work the mines under the Hallgate and Wallgate streets and also had further interviews with him regarding several streets in Scholes he wished to mine, in connection with the Birkett Bank Colliery. Unfortunately hostile proceedings were taken against him before these offers could be finalised.

In April 1846 he had gone into partnership as the managing partner with William Jowitt who hailed from Mellor in Derbyshire to lease the Birkett Bank Colliery in Chatham Street, Higher Ince for 50 years. He had invested about £2,000 in the business. In July 1848 his partner Jowitt had dissolved the partnership, sold the mine to the Ince Hall Coal Company and had kept John’s share of the sale.

Also he had advanced Mr. Whyte of Hindley who occupied the King William Colliery off Liverpool Road in Platt Bridge over £900. The mine was now worked out, the equipment, tools and materials disposed of. Now Mr. Whyte refused to reimburse the loan.

There was £2,300 in book debts yet owed to him by different parties who all refused to pay on account of his present circumstances. The Colliery in Hindley, which would be worked out in a few months, and a little brick making concern now run by his wife and relatives was all that was left of his once extensive business. The lack of capital was making the running of these businesses very difficult and his family was suffering as a result. He concluded his petition with a plea for his liberty because of his declining health:

‘For several years I have been afflicted with a rheumatic complaint and having been in prison for nearly two years on a prison diet my body is very much wasted, my strength has failed…. The infirmities of old age are coming fast upon me. My rheumatic affliction is most severe, and frequently attended by cramp, and my constitution is all together giving away, and at no very distant period (if I still remain a prisoner) I understandably must sleep in death. Then I shall be at rest’.

John Bleasdale's signature

However Sir George Grey’s decision was that he found no reasons to overrule the judge’s report and the sentence would stand.

Mill Bank Prison

John was to remain at Kirkdale until February 1851, when on the 13th he was transferred to Mill Bank Prison in London. It was to be a brief stay, in April he was transferred once again, this time to Shorncliffe Prison, near Folkestone in Kent. He was given the prisoner number 930 and assigned to cell number 4 in his prison block. The prison register described him as having a ‘mole on his right cheek, a scar near his right eye, scars on two fingers of his left hand, and that his face was highly pock marked’.

Three months later on the 29th of May 1851 John forwarded his fourth application to the Home Secretary appealing for his liberty on the grounds of his declining health. Drafted by his attorney George Dodds it stated that:

‘having been almost two and half years in prison, and the greater part of that in separate confinement his health had been very much impaired – so much so that it is with extreme difficulty he can move or make even the slightest exertion. Anticipating his removal at no distant period from this world of sorrow and suffering, and being far distant from his relatives and friends he most earnestly entreats The Rt. Hon. Sir George Grey to direct that he be sent to his native village, that he may die there in his own home and lay down his bones in the sepulchre of his fathers’.

Petition to the Home Secretary Sir George Grey, 29 September 1850

This prompted the Home Secretary to request a report on John's health from Lt. Col Sir Joshua Jebb, the Surveyor General of Her Majesty’s convict prisons. On 4 June Mr. J.D Rendle the surgeon at Shorncliffe Prison reported that the prisoner was in the early stages of consumption (Pulmonary Tuberculosis) and in his opinion the disease would cause his death in a few months. As a result a ‘Free Pardon’ was granted on 12 June 1851 and after two years six months and twenty one days in prison John was released to return home to his wife and family in Hindley.

A Free Man

Now a free man he continued his campaign for justice and three months later on 29 September 1851 he petitioned the Home Secretary once more, appealing for his intervention in the still ongoing case of the debts incurred by his imprisonment. The appeal stated that since his conviction his family had faced great hardships, he had six dependents, one of whom was mentally afflicted and who he had been supporting financially in a mental asylum. His applications to recover outstanding debts owed to him previous to his conviction had met with objections. His debtors alleged that the right of the Crown intervened and his conviction had forfeited him the right to claim payments.

He requested the Home Secretary to enact the provisions of Section 13, Chapter 28 of the 1827/1828, and Section 3, Chapter 32 of the 1829 King George IV Statutes. Namely that a warrant signed by Her Majesty and countersigned by her Secretary of State shall and will in all cases be considered a free pardon. This would restore his former rights as a free subject and grant him the legal power and authority to get in for his own use and benefit any outstanding debts due to him. The petition was presented by his friend, Richard Martinscroft and witnessed by John Ackers, a wheelwright and timber merchant from Hindley.

The Home Office replied on the 2nd of October 1851 stating that the Home Secretary had granted his appeal and that he should apply to the Treasury for Power of Attorney in order that he recover debts owed to him.

Nothing more was to be heard of John Bleasdale or the Chapel Colliery pit in the newspapers apart from a few words announcing his death. What is known is that he lived to confound the prognosis of the doctors. Through the periods of remission and decline he endured the disease for another five years before finally succumbing, dying at his home in Chapel Green, Hindley on 17 October 1856 age 61.

Graham Taylor 2025

Sources

Ancestry UK

Criminal Records 1780-1871

British Transportation Register 1787-1867

Carbon Landscape by mining historian Ian Winstanley

Find My Past Prison Registers

Google Street View

Past Forward - Yvonne Eckersley issue 73 November 2016

Lancashire Online Parish Clerk National Archives

National Library of Scotland

Newspapers.com

Wigan World