Tales From The Workhouse 2 - The Bizarre Tale of the Infant Funeral.

Introduction

A follow up to the articles ‘Wigan Workhouse & the Poor Law Union’ and ‘Tales from the Workhouse – The Story of Sarah Hartley’.

Hard Times

When thirty four year old miner Peers Thompson died in early 1866, his wife Elizabeth was forced to seek assistance from the Poor Law Union and become an inmate of the workhouse. In the days before state aid and benefits this was often the only option left to widows and unmarried mothers, and indeed anyone who had fallen on hard times.

Peers married Elizabeth Dixon in St. Thomas CE church in Chapel Street, Wallgate on 26 October 1856. At the time Peers, who was born in Parr, St. Helens was living with his family in Hansen’s Yard, off Princess Street, Wallgate.

Elizabeth’s abode was in nearby Brown Street. She had moved to Wigan from Whitehaven in Cumberland with her family sometime in the 1830’s. By 1841 they had settled in Whelley, where her father was a bleacher by trade.

After their marriage the couple lived at 97 Platt Lane, Scholes where they had four children, sadly their eldest child Mary died in 1859, aged one. The circumstances of Peer's death, which was registered in Leigh are unknown. He was buried in St. Oswald’s CE church in Winwick, on 3 February 1866.

For Elizabeth the process of becoming an inmate of the workhouse first entailed an interview with the Union Relieving Officer, who established her circumstances. Formal admission was then authorised by the Board of Guardians at their weekly meeting in their boardroom in Wallgate.

Elizabeth entered the dreaded institution in Frog Lane with her three children, five year old Thomas, three old Fanny, and James aged ten months. Firstly they were checked for diseases by a medical officer in the receiving or probationary ward. After bathing, they were issued with rough uniforms with the Union mark on them, and then allocated permanent sleeping dormitories.

She was allowed to keep her youngest child James with her until he reached his second birthday. However the strictly enforced rules meant that although she was allowed reasonable access to her other two children, they would be segregated from her and each other.

Elizabeth would be expected to earn her keep and probably would have had a domestic job and been employed either in the laundry, assisting in the kitchens or as a general cleaner.

Death in the Workhouse

On Tuesday 14 July 1868. Elizabeth’s youngest child James, now three years old, passed away in the workhouse. The Governor of the workhouse, John Lowe arranged for the funeral to take place in three days’ time at Lower Ince Cemetery. In the meantime his body was placed in the workhouse mortuary, referred to as the ‘Death House’ by the inmates.

The Governor had a team of eight inmates who acted as pall bearers for the funerals of workhouse residents, for this they were paid the sum of 3 pence for each internment. The number of coffin bearers required each time depended on the circumstances, and the age, sex and weight of the deceased.

For adult funerals a hearse was used but it was the present governor’s policy that children under the age of four could be carried by hand to the cemetery, and if appropriate two people would be allowed to carry.

Visitor’s entering or leaving the workhouse had to sign in at the porter’s lodge, and all inmates had to produce written permission to leave. On the afternoon of Friday 17th July Elizabeth met her sister Annie Devine at the porter’s lodge. Two of the designated bearers, Roger Eckersley aged 76, and Henry Travis 72, reported to the porter John Wallace, who told them to wait for two more bearers to arrive.

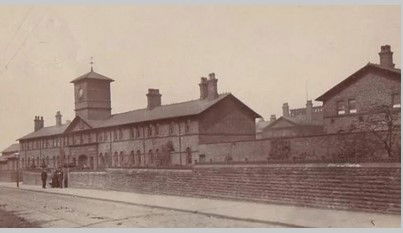

Wigan Workhouse entrance, Frog Lane.

Wigan Workhouse entrance, Frog Lane.

After a while, with no sign of the other inmates, Eckersley became impatient and told the porter that he and Travis would carry the coffin themselves as he was worried that they might not make it in time for the three o’clock burial.

At quarter to two, with Travis at the front, Eckersley to the rear, and with the two women following on behind, the funeral party set off for the two mile journey to Lower Ince Cemetery. The pair alternated from carrying the coffin by hand to carrying it with cords slung round their necks.

In Darlington Street Eckersley started struggling and asked Elizabeth to relieve him and carry her son’s coffin for a while. As they passed under the railway at Britannia Bridge on Warrington Road, Eckersley suddenly dropped young James’s coffin and collapsed face down in the road.

Efforts were made to revive the elderly man him but to no avail, he died in the street. Travis stayed with his carrying partner to arrange his recovery and transport back to the workhouse. Elizabeth and Annie had no choice but to continue the journey, carrying the coffin to the cemetery themselves where James was buried in a paupers grave, Plot L48 CE .

Two more children were buried alongside him that day. Five months old Margaret Edith Ainscough who died at 6 Crofters Arms Yard in Hallgate and Thomas Littler who died in Airey's Houses in Miry Lane, aged eight months.

As a refection of the high infant mortality rate in the mid 19th century, when one in three children died before the age of six, the grave was opened two days later for the burial of two more babies, both one month old.

Inquest

The following day Mr. C.E. Driffield Esq, the district coroner, held an inquiry in to the death of Eckersley at the Navigation Inn in Lower Ince. During the proceedings the foreman of the jury had several heated exchanges with the coroner and various witnesses, particularly Henry Travis. He tried to persuade the coroner to censor the Board of Guardians of the Poor Law Union, over the death of one of their inmates, caused by the exertion of carrying the coffin.

He gave evidence that he himself had helped the old men on occasions as they seemed quite unable to carry without assistance. He said that he had seen bearers placing coffins on the carriageway whilst they took refreshments. He also remembered the body of a seven year old child being carried by two bearers on one occasion. On the insistence of the jury foreman the inquiry was adjourned until Monday whilst more witnesses were asked to appear.

On Monday whist Roger Eckersley was being buried in Plot E251 of the Non Conformist section at Lower Ince Cemetery, the inquiry continued when the first witness was Elizabeth Thompson, who gave her version of events. More witnesses gave evidence and were questioned by the jury, the foreman taking the opportunity to press the coroner once again on bringing the Board of Guardians to account.

Eventually the coroner gave the verdict that Roger Eckersley had died from old age and decay, and therefore natural causes. In his summing up he recommended that the workhouse governor ensure that at least four persons be used to carry coffins in future.

After the death of James, circumstances changed for the better for Elizabeth, as by 1871 she had left the workhouse. She was now working in a mill and was living on lodgings with her two children at 4 Douglas Terrace, Wigan.

Return to the Workhouse

However the census of 1881 lists Elizabeth as once again being an inmate of the workhouse, the records showing that she was now classed as an imbecile, (the definition of which is a mentally deficient person unable to protect themselves against moral and mental dangers).

Elizabeth died in the workhouse three years later, aged 56. She was buried with her parents and other family members in Plot G361 CE, in Lower Ince Cemetery on 29 December 1884.

Graham Taylor

2023

Links

https://www.wiganlocalhistory.org/articles/wigan-workhouse-and-the-poor-law-union

https://www.wiganlocalhistory.org/articles/tales-from-the-workhouse-the-story-of-sarah-hartley

Sources

Ancestry.co.uk

Wigan Observer & District Advertiser 25 July 1868

Wigan World