Tales from the Workhouse 1 - The Story of Sarah Hartley

Introduction

During research for a previous article, ‘Wigan Workhouse and the Poor Law Union,’ I selected various people at random who were listed on the census taken 3 April 1881, as being inmates of Wigan Union Workhouse. Later I researched these individuals to see what life had in store for them.

This is the story of one such inmate, an unaccompanied ten year old girl by the name of Sarah Hartley. At first glance it appears she was just another orphan living in the stark Victorian institution. In fact Sarah had close family living not too far away, this begs the question of why she was in the workhouse in the first place, and what fate awaited her.

Wigan Roots

The youngest child of John Hartley, a coal miner and Ellen Mather, Sarah was born 27 April 1870 at Brookside Row, Brook Street, Lower Ince, Wigan. She was baptised 21 August 1870 at All Saints Parish Church in Wigan.

Sarah’s paternal ancestors are an old Wigan family who can be traced back to the 1700’s living in the Wallgate area of town. Their surname was actually Hartliff but by 1851 the family name had been corrupted to Hartley.

The maternal side of the family, the Mather’s were natives of Prescot, Ellen’s birthplace in 1845. When she was just an infant her father William Mather, a tailor by trade uprooted his family and relocated to Bolton some twenty odd miles away, where the youngest member of the family William Jnr was born in 1850. The following years census finds William, his wife Margaret (nee Sim) and their six children living at 16 Pit St in Bolton. Ellen’s mother died in Pit Street two years later, aged 37, when Ellen was just seven years old.

The 1861 census shows fifteen year old Ellen living in lodgings at 138 Chapel Lane in Wigan and her occupation is shown as cotton mill worker. Four years later on 8 August 1865 she married John Hartley at Wigan Register Office. Her address at the time was 132 Hardybutts, John was living across the road at number 127, so this is where Sarah’s parents obviously met.

After their marriage they lived at John’s home at 127 Hardybutts, where Elizabeth Ellen was born later that year and John Thomas was born in 1868. Shortly after the family moved to Brook Street in Lower Ince, the birth place of Sarah. It was here on 18 February 1871, when Sarah was just ten months old, that her mother died, aged 25 of bronchitis. She was buried in a paupers grave in Wigan Cemetery three days later by the vicar of St. George’s church, Revd. P. Hains.

Two months after Ellen’s death the 1871 census shows Sarah’s father, brother and sister living with her grandparents Thomas and Elizabeth Hartley at 15 Brown Street in the Wallgate area of town. Bizarrely Sarah is not listed on the census and her whereabouts are unknown. It was possibly an oversight by the census enumerator as her grandfather Thomas and the husband of her aunt, James Prescott are also not listed, although they were resident at the address at the time.

In 1876 Sarah’s grandfather Thomas died, followed three years later in May 1879, by her grandmother Elizabeth. That same year Sarah’s father John and her brother John Thomas emigrated to New Zealand. They sailed from Plymouth on 24 August on board the SS Opawa, arriving in Nelson on New Zealand’s South Island on 27 Nov 1879.

Sarah, aged nine and her thirteen year old sister Elizabeth were left behind in Wigan. With their two closest relatives, their aunt Ellen and uncle Richard now both married with growing families, the two girls were in a predicament. At nearly fourteen Elizabeth was old enough to work for her keep and went to live with her Aunt Ellen as a domestic servant. Sarah’s life took a different path.

Wigan Union Workhouse

The admission and discharge registers of Wigan Union Workhouse for this period did not survive to confirm it, but it is highly likely that this was the moment Sarah was admitted into the workhouse in Frog Lane.

What is certain is that Sarah next appears on the 1881 census as a resident of the workhouse, where the Master and Matron, John and Alice Lowe were responsible for her welfare. At the time there were 511 inmates, 290 males and 221 females. Of the under fourteens, there were 93 boys and 79 girls, seventeen of whom were infants under the age of two.

It must have been a traumatic experience for the young Sarah to find herself shut behind the high walls, subject to a harsh daily regime with strict rules and no family for support. It was a constant routine of early to bed and early to rise, with challenging work in between.

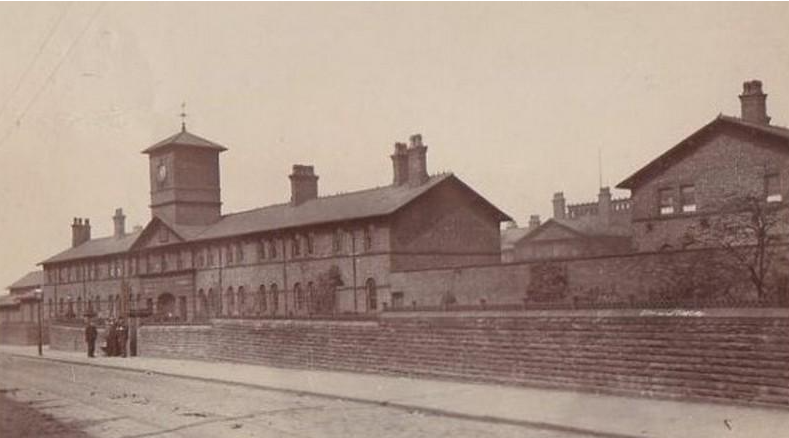

Wigan Workhouse, Frog Lane.

Wigan Workhouse, Frog Lane.

There was no time for play, she would have been expected to help the female inmates with domestic chores of cleaning and polishing or helping in the laundry or kitchen. Sunday was a day of rest but Sunday school and attendance at a church service was compulsory so there was little time for relaxation.

The 1834 Act for Poor Law Unions required them to provide at least three hours a day of schooling, and an 1880 Act made education compulsory up to the age of ten. So Sarah’s day would have been broken up by receiving a rudimentary education from teacher Jonathon Caddy who hailed from Ulverston in North Lancashire. Later records show that at some point Sarah had received education at St. Thomas’s school in Caroline Street, Wallgate and attended the adjacent St. Thomas’s church

Edgworth Children’s Home

Sarah’s uncle, Richard Hartley, a billiard marker and later a professional player, was to take on the responsibility of being her guardian. On 8 September 1884 he enrolled his fourteen year old niece into the Stephenson Children's Home at Crowthorn, near Edgworth, some six miles to the north of Bolton.

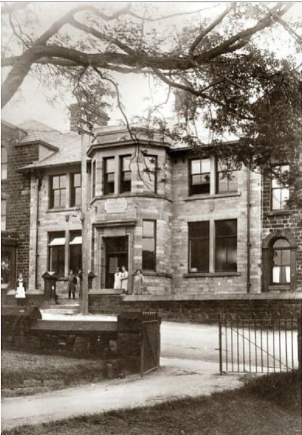

Edgworth Children's Home

Edgworth Children's Home

Her admittance papers show that Richard agreed to pay two shillings per week for her maintenance and he further agreed not to interfere with her care in any way. Among other conditions of her admittance, he also agreed ‘to the child being sent to any situation within this country or abroad’.

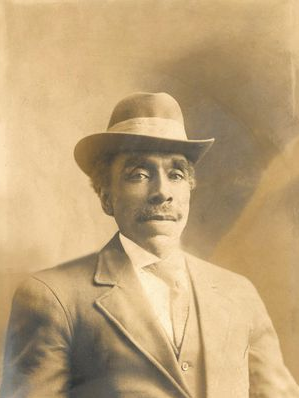

The Children’s Home had been founded in Lambeth, London in 1869 by Wesleyan Methodist Minister, Revd. Dr. Thomas Bowman Stephenson, along with two associates, Alfred Mager, a banker’s cashier and merchant businessman Francis Horner.

Rev. Thomas Bowman Stephenson (1839-1912)

Rev. Thomas Bowman Stephenson (1839-1912)

The Children’s Home later moved to a permanent address in Bonner Road in Bethnal Green, London. Stephenson saw it as his mission to help poor and disadvantaged children and the home’s motto was ‘To seek and to save that which is lost’. He eventually opened several more homes and orphanages in England and the Isle of Man.

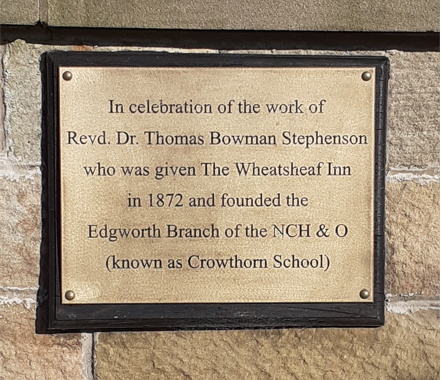

Tribute - Stephenson Plaque Stephenson had travelled the Methodist Ministry circuit and had spent six years in the Manchester and Bolton areas. It was here that he met wealthy Lancashire industrialist and philanthropist, James Barlow, Mayor of Bolton between 1867 and 1869. Barlow was Chairman of Edgworth Spinning Company and proprietor of textile manufacturers Barlow & Jones Ltd.

Tribute - Stephenson Plaque Stephenson had travelled the Methodist Ministry circuit and had spent six years in the Manchester and Bolton areas. It was here that he met wealthy Lancashire industrialist and philanthropist, James Barlow, Mayor of Bolton between 1867 and 1869. Barlow was Chairman of Edgworth Spinning Company and proprietor of textile manufacturers Barlow & Jones Ltd.

Barlow, who lived at Crowthorn, was a staunch Methodist and temperance campaigner. He financed the building of the Edgworth Wesleyan Chapel, laying the foundation stone on 14 June 1862. In 1871 he bought a 70 acre site in an isolated location on nearby Edgworth Moor. It consisted solely of a public house, the Wheatsheaf Inn, and several outbuildings. He donated the site to the Children’s Home for use as their second home, also he gifted Stephenson £5,000 for maintenance costs.

Wheatsheaf Inn

Wheatsheaf Inn

The Wheatsheaf Inn, which was considered a den of iniquity by Barlow with its drunkenness, gambling, and cock fighting, was closed and converted to a main home which first opened its doors in April 1872. The first Governor was Alfred William Mager, one of the three original founders of the London Children’s Home. He initially had twenty four boys and four girls under his care.

Tribute to James BarlowIt was a hard, demanding life living on the moors for these first pioneers who helped to develop the site and create a community around it. Eventually more children’s houses were built along with a schoolhouse, cottage hospital, bakery, and laundry. A farm and dairy were developed and stone was extracted from a local quarry to provide material for the construction of a reservoir to supply water for the residents.

Tribute to James BarlowIt was a hard, demanding life living on the moors for these first pioneers who helped to develop the site and create a community around it. Eventually more children’s houses were built along with a schoolhouse, cottage hospital, bakery, and laundry. A farm and dairy were developed and stone was extracted from a local quarry to provide material for the construction of a reservoir to supply water for the residents.

At the time of the 1881 census, when Sarah was an inmate of Wigan Workhouse, the records shows that the Edgworth estate now covered 100 acres. The Governor Alfred Mager was now accompanied by his wife Elizabeth, who held no official position, and niece Annie Madeline. Butt, a scholar at the school, all three being natives of Bath in Somerset.

Alfred & Elizabeth Mager

Alfred & Elizabeth Mager

Mager had a staff of nineteen under him to look after the 108 children, or inmates as the census classified them, and the dependent children of the staff. He had four matrons and two assistant matrons to look after the welfare of the children in the houses, with a school master and two teachers taking care of their education. Three labour masters supervised the older children who worked either on the farm or helped with jobs around the homes and gardens. Being a Wesleyan Methodist organisation, when the children reached a responsible age they were voluntarily asked to sign the temperance pledge.

Other essential staff employed for the smooth running of the home included a farm bailiff, an assistant clerk, seamstress, laundress, baker, cook, dairywoman, gardener, and carter. Including family of the permanent staff the census lists 135 residents in total at Edgworth. They came from far and wide, from Newcastle in the north to Kent in the south and from Wales, Ireland, and the Isle of Man. The average age of the children in the home was eleven and half .

Home Child and a New Life in Canada

A child migration scheme had been founded in 1869, under which more than over 100,000 children, many, ex-workhouse inmates, were sent from children's homes and orphanages in Britain to Canada. The pioneers of this scheme were Annie McPherson, Maria Rye, and Thomas Barnado who founded the well-known Dr. Barnado’s Homes.

Eventually over fifty organisations used this resettlement scheme which continued for seventy years up to the beginning of the Second World War. These migrants were called ‘Home Children’ because most went from an emigration agency's home for children in Britain to its Canadian receiving home. They were then either adopted or found positions on rural homesteads working as farm hands or domestic helps.

In 1872, Reverend Stephenson set up his own child migration scheme. He had family connections in Canada and through them contacted the Methodist Church and farming communities in Hamilton, Ontario. The towns authorities were sympathetic to Stephenson’s plans but were concerned that children from large English towns would be unsuitable and not have the necessary skills and experience to live and work on rural farms. To reassure them Rev. Stephenson promised that only children of working age would be sent and that the boys would be trained in farming techniques and the girls as domestic servants.

A local committee was then formed which raised $5,400 to buy and furnish a receiving home and distribution centre. A suitable property was found at 1078 Main St East in Barton Township. The large house, set in eight acres of land with orchards and fruit and vegetable gardens was considered by Stephenson to be an ideal location for the children.

Main Street East, Hamilton, Ontario

Main Street East, Hamilton, Ontario

Accordingly the first party of forty nine child emigrants travelled out to the new receiving home in Hamilton in 1873. They were under the supervision of Francis Horner, one of the co-founders of the Children’s home.

After being trained as a domestic housekeeper where she was taught skills such as cooking, kitchen work, laundry and needlework Sarah was registered as a British Home Child. On 6 June 1886, aged 16, she sailed from Liverpool onboard SS Sarnia bound for a new life in Canada. The party of thirty four girls and one boy was under the supervision of a guardian by the name of Miss Smith.

Upon their arrival at Port Levy, on the south banks of the St. Lawrence river across from Quebec City, the party travelled 541 miles by train over several days, via Montreal and Toronto to the receiving home in Hamilton.

After a settling in period Sarah was eventually assigned as an indentured servant on Colonel John Murray’s farm in Stewarttown, some 40 miles or so north of Hamilton, on the outskirts of Toronto. At the farm Sarah was to meet farmhand and future husband, John Henry Shepherd, the son of a Black slave.

John Henry Shepherd (1852-1948)

John Henry Shepherd (1852-1948)

John was just an infant in the mid 1850’s when his mother fled with him from enslavement in America to Canada via the ‘Underground Railroad’.

The Underground Railroad

During the era of slavery, the Underground Railroad was a metaphor for the network of routes, places, and people that helped enslaved people in the American south escape to the northern free states. It comprised of Methodists, Quakers and free slaves who returned to help others escape. The organisation transported people long distances via a network of safe houses, barns, churches, and businesses.

The 1793 Fugitive Slave Act decreed that the owners of enslaved people and their ‘agents’ had the right to search for escapees within the borders of free states and if caught they were to be returned to their owners. Following the Second Act of 1850 which increased the penalty for assisting runaway slaves to a $1000 fine and six months imprisonment, many fugitives crossed the border into Canada where slavery had been officially banned in 1834.

According to some estimates, between 1810 and 1850, the Underground Railroad helped to guide one hundred thousand enslaved people to freedom. As the network grew, the railroad metaphor stuck. The fugitives travelling along the routes were called ‘passengers’. They were often helped to escape from plantations, usually at night, by ‘conductors’, who guided them from safe-house to safe-house, often with ten to twenty miles between each stop. Lanterns in the windows welcomed them and promised safety. Bounty hunters who could be paid up to $1,200 for apprehending fugitives were frequently hot on their heels.

The places that sheltered the escapees were referred to as ‘stations’,” and the people who sheltered them were known as ‘station masters’. One such ‘station master’ was American Quaker and abolitionist Thomas Garrett whose home in Delaware County, Pennsylvania was a stop along the Underground Railroad. Those who had arrived at the safe houses were known as ‘cargo’. The Underground Railroad was at the heart of the abolitionist movement, heightening divisions between the North and South, and as such was a direct contributing cause of the American Civil War of 1861-1865.

Mrs Shepherd and her son John Henry, who it is believed were the first Black settlers in the area, were welcomed onto Colonel Murray’s farm in Esquesing Township. Living in a small cabin in Georgetown Park, they walked daily along the railway tracks to the Murray farm where Mrs. Shepherd worked as a housekeeper. Following the death of his mother sometime before the 1871 census young John went to live on the Murray farm with the Colonel and his family.

In December 1887, eighteen months after arriving in Canada seventeen year old Sarah married John Henry Shepherd at St. George’s Anglican church in Georgetown. John’s exact age is not known but is thought to have been at least fifteen years her senior. The couple settled in the township of Esquesing, near to Colonel Murray’s farm in Stewarttown and between 1888 and 1897 raised a family of four girls and two boys. Violet Harriet, Jessie Hartley, Flora Mabel, Johnetta Elizabeth, Henry Thomas, and John Alfred.

In 1906, Richard Hartley Jnr, the son of Sarah’s uncle and guardian Richard Snr, emigrated from Wigan with his wife Alice and son Lawrence to Ontario, settling in Collingwood, sixty three miles north of Sarah’s home in Georgetown. It is not known if Sarah was aware of the fact that her cousin was living so close, and that if any correspondence took place between them.

In 1914 the First World War in Europe intervened in the lives of Canadian citizens. Canada's legal status as a British Dominion left foreign policy decisions in the hands of the British Parliament, therefore the British declaration of War on 4 August 1914 automatically brought Canada into the conflict. However the Canadian government had the freedom to determine the countries level of involvement.

At the time Canada’s army consisted of just 3,100 regular soldiers under arms, miniscule compared to the British and German armies. They had to play catch up fast and decided that the 59,000 strong part time Militia Force would not be mobilised. Instead a new independent Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) would be raised, with Militia members at its core.

Like countless other mothers Sarah had to suffer the pain and anguish of seeing her two sons, Henry, and John, go off to fight the war in Europe. Racial discrimination was still prevalent in the early 20th century and most Black soldiers who served in the CEF remained segregated in labour units. Few were allowed to serve in combatant roles, Henry and John Shepherd were exceptions.

Henry enlisted in June 1915 and was away from home for four years, seeing active service in France and Flanders with 2nd Battalion CEF. In June 1916 he was wounded in action in the Ypres Salient in Belgium and again in September during the Battle of the Somme in France, suffering gunshot wounds to his head, neck, and shoulder.

On 3 October 1916, after receiving treatment in Manchester, Henry was deemed fit enough to go on a week’s furlough, he took the opportunity of visiting Wigan. Here he met his mother’s sister and her family. His aunt Elizabeth had married John Marsh in 1890, they had nine children but the eldest three had all died in childhood. John was a miner by trade, but also a licensed victualler, at the time of Henry’s visit his aunt and uncle were running the Woodhouses Inn in Woodhouse Lane.

Henry visits his Wigan relatives at the Woodhouses Inn in 1916Henry spent the last two years of the war in rehabilitation, then as an instructor with the 6th Battalion CEF, on the south coast of England at Seaford in Sussex. On his return home he resumed employment at Georgetown paper mill and re-joined the Halton Rifles Militia.

Henry visits his Wigan relatives at the Woodhouses Inn in 1916Henry spent the last two years of the war in rehabilitation, then as an instructor with the 6th Battalion CEF, on the south coast of England at Seaford in Sussex. On his return home he resumed employment at Georgetown paper mill and re-joined the Halton Rifles Militia.

John enlisted in December 1915 in Toronto and entered the theatre of war in France in March 1917. Six months later he was seriously wounded in action whilst serving with 123rd Pioneer Battalion near Lens in France, suffering shrapnel wounds to his left thigh. After his evacuation and medical treatment in England he was briefly re-united with his older brother when he was posted to the same camp as Henry at Seaford in Sussex. John returned home to Canada in January 1919 but was medically discharged from the army on medical grounds when it was found he was suffering from diabetes.

John Alfred Shepherd (1897-1970)

John Alfred Shepherd (1897-1970)

Lawrence Richard Hartley, the grandson of her guardian enlisted into the CEF in December 1915. He died, aged 20 in August 1917 during the Battle of Hill 70 in France, whilst serving with the 75th Infantry Battalion. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Vimy Memorial in France. He is also commemorated on the Cenotaph in his Home town of Wigan.

Post War

In 1926 Sarah suffered the heartache of losing her youngest daughter Johnetta who died aged just thirty three. The following year Sarah’s father died in New Zealand. it is not thought that he married again and it is not known if she ever had contact with him again. Her sister Elizabeth Ellen died in Wigan in 1951 aged 85. Her brother John Thomas settled in New Zealand, he married Grace Middlemiss in 1901 and had seven children. He and Sarah corresponded by letter over the years. He died in Auckland in 1957, aged 88.

Sarah, the matriarch of the Shepherd family died on Thursday 31 July 1941, aged 71, at her home in Victoria Street, Georgetown. She was buried two days later in the town’s Greenwood Cemetery alongside her daughter Johnetta. Two years later her daughter Jessie also died, aged 53.

Her grandson Reginald Roy Blair, the son of Sarah’s third born daughter Flora, enlisted in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry on 18 September 1939 in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Whilst in England in 1943 he married Nancy Frederica White in Lancing, near Brighton in Sussex. They had a baby son, named James before he went off to war. Reginald was killed in action in Italy on 20 December 1944 and was initially buried by his comrades in a battlefield grave. On 29 March 1946 he was re-buried in Ravenna War Cemetery, a Commonwealth concentration cemetery near Bologna on the Adriatic coast.

Ravenna War Cemetery

Ravenna War Cemetery

Sarah's sons Henry and John were both volunteer fireman and Henry became the first Black Chief of the Georgetown Fire Department.

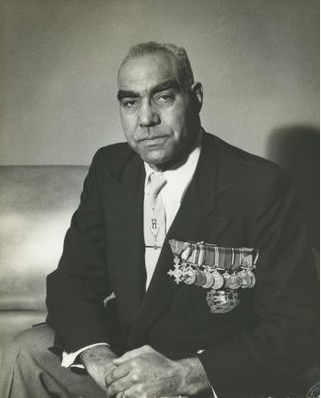

Henry had a long and distinguished military career and in June 1944 was named in King George VI‘s Birthday Honours List, being appointed to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE). Sarah was not alive to see him receive his honour from the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, Albert Matthews at a ceremony in Toronto.

Henry Thomas Shepherd M.B.E (1895-1960)

Henry Thomas Shepherd M.B.E (1895-1960)

The 1945 Alphabetical Voters List compiled at the end of WW2 shows Henry and his wife Susanna Maud living in Chapel Street. His sister Flora Blair and her husband James were living in nearby Morris Street. His father John Henry was living with widowed daughter Violet Cook in Victoria Street, fittingly John Henry, the son of an American slave is described as a gentleman. He died in 1948 and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery alongside his wife Sarah and two daughters.

Shepherd Family Grave

Shepherd Family Grave

Due to his achievements during his military career and in later civilian life Henry Shepherd became a much respected member of the community in Georgetown and further afield. Over the years following his death, he has continued to receive recognition and has been acknowledged in several history books, publications, and newspaper articles.

In 2016 his life story was featured on a CBC Television special and in that same year, he featured in an exhibition of Black soldiers at the National War Museum in Ottawa, organised by historian Kathy Grant. Two years later the Shepherd family was also featured at the Newmarket Old Town Hall for their first Black History Month exhibition.

On 2 October 2021, in a tribute by the local community, officials from Halton Hills council gathered with friends and family for the official naming ceremony of the ‘Henry Thomas Shepherd MBE Park’, close to his former home on Chapel Street. A ‘Story Board’ honours the historical contribution of the Shepherd/Hartley family to the local community, as well as Canada.

Postscript

Edgworth benefactor Alderman James Barlow died in 1887. His son Sir Thomas Barlow became Royal physician to three monarchs, Queen Victoria, King Edward VII, and King George V. His daughter was a renowned Egyptologist and donated many items to Bolton Museum. His grandson Sir James Barlow married the granddaughter of Charles Darwin. In later years the Barlow family home on the Greenthorne Estate in Crowthorn found fame when it became a conference venue during Mahatma Gandhi’s visit to Lancashire in 1931.

Revd. Thomas Bowman Stephenson, the founder of the Children’s Home retired in 1907, his successor being Revd. W. Hodson Smith. The following year his organisation was renamed the National Children’s Home (NCH). He died four years later in 1912. Approximately 3,400 children were sent from the NCH, (many hundreds of them trained at Edgworth), to the receiving home in Hamilton between 1873 and 1931, when the Canadian home finally closed.

The original Wheatsheaf Inn that had been built in 1797 and became the first children’s home was rebuilt in 1926. Edgworth, the ‘The Home on the Moors’ ceased to be a children’s home in 1953. Changing its name to Crowthorn School, it became a residential school for children with special needs. It finally closed in 2002 and the site then sold off.

Alfred Mager, the first Governor of Edgworth retained his position for thirty five years up to his retirement in 1907. He died in Surrey in 1915, aged 79.

Wigan Union Workhouse closed its doors for the final time on 1 April 1930 and became the Public Assistance Institution (PAI) caring for the elderly, chronically sick, unmarried mothers, and vagrants. On the creation of the National Health Service Act in 1948 the site became the Frog Lane Welfare Home, caring for geriatric residents. By 1972 the home and hospital were closed and the residents re-housed at the Billinge and Whelley sites in the town. For a period homeless families were temporarily housed on the site, but the remaining buildings were finally demolished in the 1990’s to make way for a new housing development.

Legacy

Sarah Hartley, the young English girl who had spent her adolescent years at Wigan Union Workhouse and Edgworth Children’s Home has left an enduring legacy in Canada that is celebrated to this day.

Sarah Shepherd with grandchildren

Sarah Shepherd with grandchildren

With six children, twenty one grandchildren and fifty one great grandchildren it is unsurprising that over 10 per cent of the modern population of Canada is estimated to be a descendant of a British Home Child.

Sarah Hartley Shepherd (1870-1941)

Sarah Hartley Shepherd (1870-1941)

Graham Taylor 2022

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Kathy Brooks and her husband Craig for supplying personal family information and photos, courtesy of the Shepherd Family Collection.

Sources

American Battlefield Trust

Ancestry BMD & census records

British Home Child International

British Home Children in Canada

Canadian Voters List 1935-1980

Canadian Military Honours & Awards Citation Cards 1900-1961

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

"From Edgeworth to Crowthorne" - The Story of a Lancashire Children's Home, Anita Forth

Government of Canada Library & Archives

Halton Hills Images

History - Child Migration

National Children's Home

The National Archives

Wikipedia

Wigan World

WW1 CEF Attestation Papers & Personal Files 1914-1918

WW1 CEF Battalion War Diaries