Stephen Walsh MP for Ince 1906-1929

Stephen Walsh was born in Kirkdale on 26 August 1859. His parents were of Irish descent. His father, John Walsh, died before his son’s birth, and his mother passed away while he was still an infant. As a result, he was sent to Kirkdale Industrial School and Orphanage.

In 1872, he went to live with his brother and at the age of 13 became a working miner at Ashton-in-Makerfield. It was there that he met his future wife, Anne Adamson, daughter of John Adamson, an Ashton miner. At the time, Anne was working on a colliery pitbank. The couple married on 16 August 1885 and went on to have four sons and six daughters.

Rise in the Trade Union Movement

Walsh became an active trade unionist and, in 1890, was elected district officer and secretary of the local union organisation. His integrity and intelligence quickly earned him the confidence of his fellow miners.

Herbert Tracey later observed: “The conditions of employment at that time were not particularly attractive, and his commencing wage was only one of ten-pence for a ten-hour working day. It was a marked characteristic of that period that education was a blessing shared by few of the adult miners, and inasmuch as many of them were practically illiterate, they were not slow to appreciate the advantages which Stephen Walsh possessed. His sterling character and keen intelligence, too, commanded their respect and confidence, and he was invariably selected to uphold their interests whenever any differences arose.”

By 1901 Walsh was appointed agent of the Lancashire and Cheshire Miners’ Federation, a position which cemented his role as one of the most trusted voices of the mining communities.

Parliamentary Career

Walsh was also a committed member of the Labour Party, and in the 1906 General Election, sponsored by the Miners’ Federation, he was elected to the House of Commons to represent the Ince division.

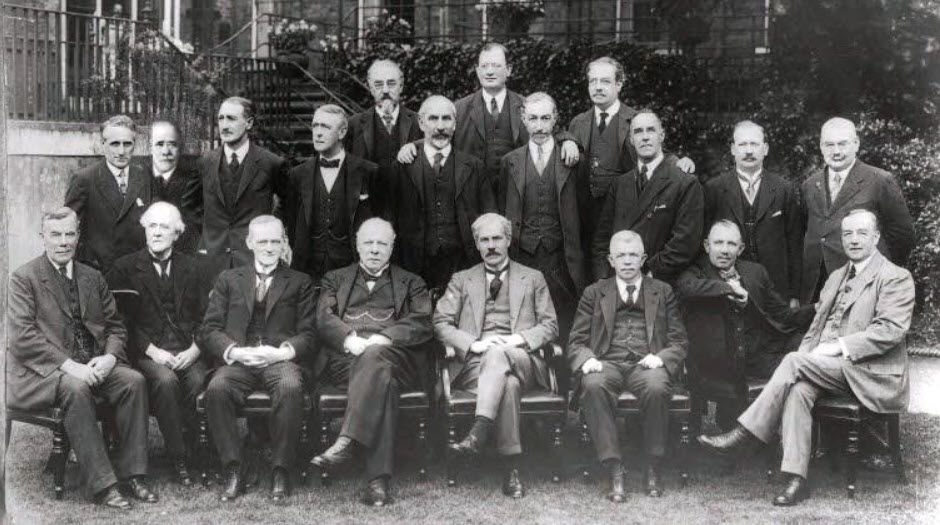

1906 Labour MP's group - Stephen stood behind Keir Hardy

Although a man of small stature and modest presence, Walsh made an impact in Parliament. He spoke with effect on industrial questions and contributed to major debates, including those that shaped the Mines Act of 1911 and the Minimum Wage Act of 1912.

During the First World War, Walsh strongly supported recruiting campaigns and was an advocate of conscription. In recognition of his service, David Lloyd George appointed him Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of National Service (March to July 1917) and later to the Local Government Board (July 1917 to January 1919).

His eldest son, Arthur, was killed in action in 1918, a loss from which Walsh never fully recovered.

Unveiling the Ince in Makerfield Cross "War Memorial" 30th August 1924

Walsh was re-elected for Ince in the 1918 General Election and, in 1922, was appointed Vice-President of the National Union of Mineworkers. He became recognised as an expert in wage negotiations and served as chairman of the miners’ section of the English conciliation board.

Minister of War

When the Labour Party formed its first Government in January 1924, Ramsay MacDonald appointed Walsh Secretary of State for War. Though initially greeted with scepticism due to his lack of military background, he quickly won respect in Whitehall for his energy, fairness, and determination.

Ramsay MacDonald's Cabinet - (Stephen - middle row, 2nd from left)

Walsh was also remembered for his humour and humanity. Unfamiliar with military rank, he solved the problem by addressing all officers alike as “captain.” He and his wife had been inseparable; on one occasion, when a general sought a private interview, Walsh gestured to his wife by the fire and said, “Out with it, lad — Mother and I have no secrets.”

Impact on Ince

For the people of Ince, Stephen Walsh was more than a national politician — he was their champion. Having risen from the pits himself, he understood the struggles of mining families and consistently carried their voices into Westminster. His advocacy for better pay, safer conditions, and recognition of the miners’ contribution gave the community a sense of pride and representation.

For twenty-three years, the people of Ince placed their trust in Walsh, returning him to Parliament election after election. They admired him not only for his loyalty to their cause, but also for his unshakable honesty and humour. To his constituents, he stood as proof that one of their own could rise from orphan and pit boy to Cabinet minister without ever losing touch with his community.

Death and Legacy

Stephen Walsh died at his home, 8 Swinley Road, Wigan, on 16 March 1929, aged 69.

He was buried at Holy Trinity Church in Ashton-in-Makerfield.

His life — from orphaned miner’s boy to War Minister — embodied the struggles and triumphs of the working-class movement in Britain and left a lasting mark on Ince and its people.

Michael Nelson 2025