Report on an outbreak of Typhus in Scholes and Ince in 1891

A report produced identifying the probable cause and the circumstances in which individuals were affected. None of the affected people were interviewed, and much of the surrounding information on the conditions is based on hearsay and doesn't address the responsibilities of landlords and the Council. It is probably worth noting that quite a lot of the people living in the streets affected would be parishioners and regular church goers at St. Patrick's Church.

The report itself is a very comprehensive, analytical and forensic report from Monckton Copeman, who would become world famous leading authority on diseases of this type.

Dr. S. Monckton Copeman’s Report to the Local Government Board on an Outbreak of Typhus Fever in the Wigan and Ince-in-Makerfield Urban Sanitary Districts.

It having come to the knowledge of the Board, through the Quarterly Return of the Registrar-General, that at Wigan an epidemic of typhus fever had broken out which had been the cause of several deaths during the last quarter of 1891, an inquiry was ordered into the circumstances of the outbreak, and I was directed to make it.

Wigan Urban Sanitary District is an iron, brass, and cotton manufacturing town in Lancashire of about 50,000 inhabitants, in an important coal district, several collieries being located actually in the town itself.

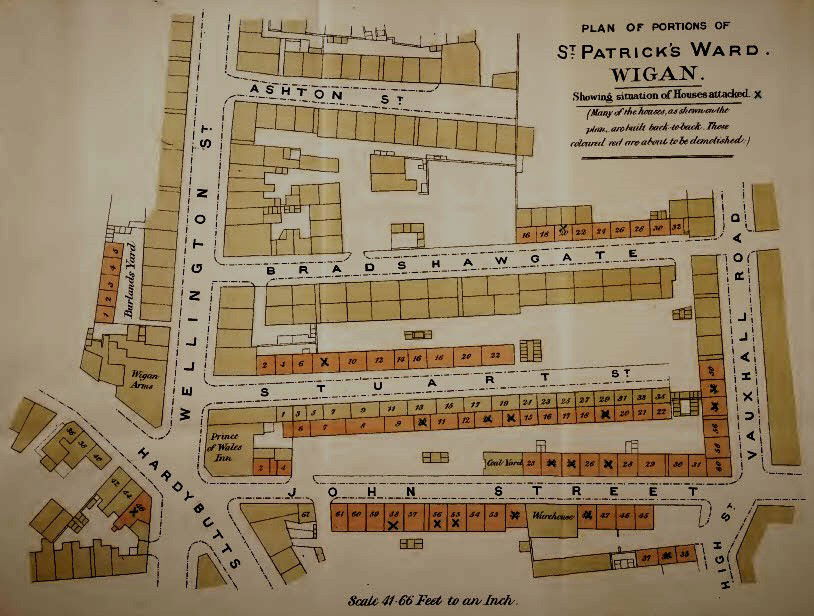

On arriving at Wigan, I at once put myself in communication with the officers of the Sanitary Authority, and soon learned that up to the date of my visit above 70 cases of typhus had occurred in the town and neighbourhood, and that 10 of them had proved fatal. Also, I learned that the outbreak of fever had been almost entirely confined to a portion of the town called Scholes, situated in the St. Patrick’s Ward. Accordingly, I visited this neighbourhood, with the object of making a thorough inquiry into the sanitary conditions of the affected area. And here I found that the knowledge of the Inspector of Nuisances (Mr. Sumner) was of great value to me, this officer being fully acquainted with the local circumstances of the various districts under his charge.

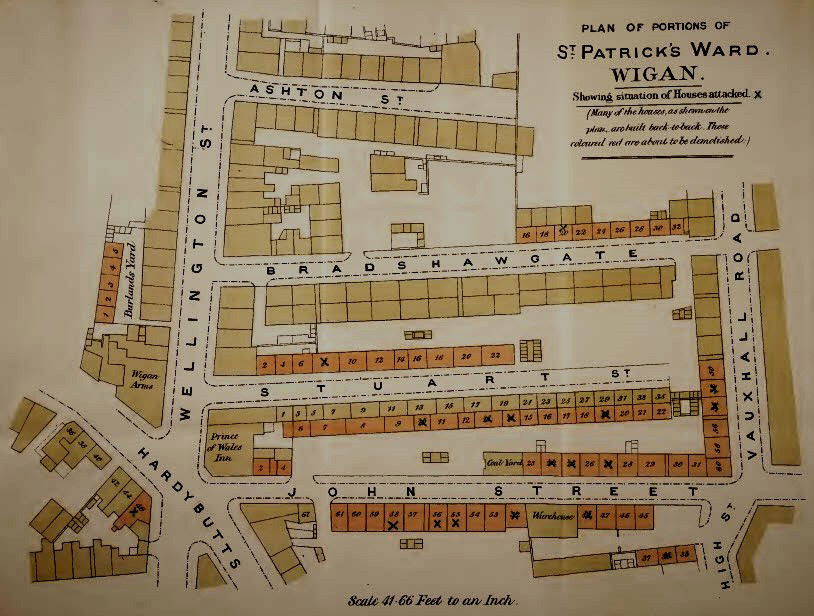

In St. Patrick’s Ward, which is not inaptly named seeing that the greater number of the inhabitants are of Irish extraction, are to be found the worst slums in Wigan ; this portion of the town containing a number of courts, the houses in which, as will be seen from the accompanying plan, are in many instances built “ back-to-back.” Houses of this class each contain for the most part three small rooms; a single room on the ground floor, opening directly to the court or street, used as kitchen, living, and sleeping room, and other two sleeping rooms, on the floor above, communicating with one another.

Owing to the method of their construction (back-to-back), the only means of securing ventilation for many houses is by means of a window (generally securely fastened up) in each room, and by the street door of the lower room. At the same time the floor and cubic space of the living room are considerably encroached upon by a large bed, often of the four-poster type, which accommodates several members of the family at night. Furniture of other kinds, however, for the most part there is none, beyond, perhaps, a small table and a broken chair. Not infrequently there is an additional room below the level of the street, at one time used for a weaver’s loom, which being no longer put to this purpose, is time after time made a convenient receptacle for the disposal of cinders and other household refuse, such as potato peelings, cast into it through the aperture which was once a window.

The fact that many families in Wigan are living over heaps of decomposing material of this description, containing, as it does, a large percentage of organic matter, may be of importance as increasing their susceptibility to disease.

The number of persons inhabiting such a house as I have described not unfrequently amounted to eight, ten, or even more individuals of both sexes, often including one or more adult male lodgers, who, I was informed, not infrequently, though in receipt of good wages, live on for years with the same family. Owing to the number of persons living in each house, the sexes are mingled in the most promiscuous manner. The houses, both inside and out, are conspicuous for tilth and squalor, and it appears that some of these places are made use of as brothels by the very lowest class of persons, a state of things which is only partially prevented by frequent nocturnal visits by the police. The bedding, so called, often swarms with vermin, so that in several instances in which during the outbreak under investigation it has been removed for purposes of disinfection, it was found to be in so filthy and dilapidated a condition as to necessitate its immediate and entire destruction, A few houses in the neighbourhood to which I particularly refer, were, I found, uninhabited, probably owing to the fact that in several instances, the windows and floors had practically disappeared. In one or two instances I found the remains of the flooring strewn with human excrement.

The sanitary committee have made some attempts to improve the state of things prevailing in this part of the town, but their efforts have in great measure been rendered futile by the incorrigible habits of the people. Thus, owners have been required to supply doors fitted with locks to the privies, a block of which separated from the houses, as seen on the plan, are provided for the use of the inhabitants of each court or alley, the occupier of a house being supposed to be held responsible for the due cleanliness of the particular closet of which he has the key.

These closets are provided with metal pails beneath the seat, which are periodically emptied by the town scavengers. As a matter of fact, however, I found in certain instances that the door had been broken down and sometimes altogether removed, having probably, as I was informed, been chopped up for firewood. In other cases, the pails had disappeared, having been found useful as wash-tubs, while the condition of the actual closet was often foul in the extreme; the whole space, not only beneath, but also in front of, and above the seat, being fouled with a mass of excreta, the more fluid portion of which formed pools on the floor, or even in the yard outside. Usually speaking, provision for the disposal of ashes and other household refuse has been made by placing tubs in a covered space between the backs of two adjoining lines of privies, but the usual result as I found it, is that the one or two tubs nearest at hand having become filled to overflowing, refuse is afterwards simply shot into the entrance to the space containing the tubs or on the ground outside, the tubs at the further end of the space remaining empty.

Some of the yards are altogether unpaved, though in certain cases this defect has been partially amended quite recently in consequence of the action of the sanitary authority. Where this has not been done, the surface is often extremely uneven, the hollows becoming the site of stagnant pools of slop water. Such unevenness was, in, many instances at any rate, due, as I proved by the use of a spade, to the presence of masses of house refuse which extended in some cases to the depth of a foot or more from the surface.

Of late, a number of houses in these courts have been condemned as unfit for human habitation; but for the most part they have not been pulled down as yet, there appearing to be some difficulty in the provision of suitable accommodation for the inhabitants elsewhere.

It will, I think, be obvious from what has been said, that the particular portion of the town to which my visit of inspection was especially directed, provided every facility for the spread of infectious disease, when once it was introduced among the people living there; indeed, it is a matter rather of wonder that they should ever be long free from illness of the zymotic type.

I next directed my attention to the circumstances of the outbreak itself, and as a first step obtained from the Medical Officer of Health (Dr. Barnish) a list of all the typhus cases that had occurred up to the time of my arrival on the spot, together with particulars as to their sex, age, date of attack, and address. From this I found that so far there had been apparently 78 cases of the disease in 48 families,* with 10 deaths, and further, as I have already stated, that the majority of the cases occurred in a part of the town in St. Patrick’s Ward, known as Scholes.

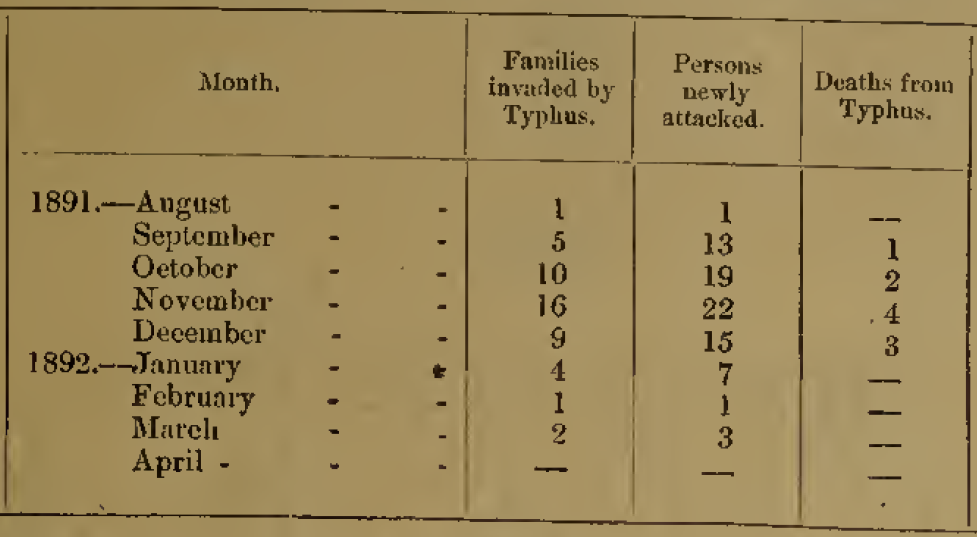

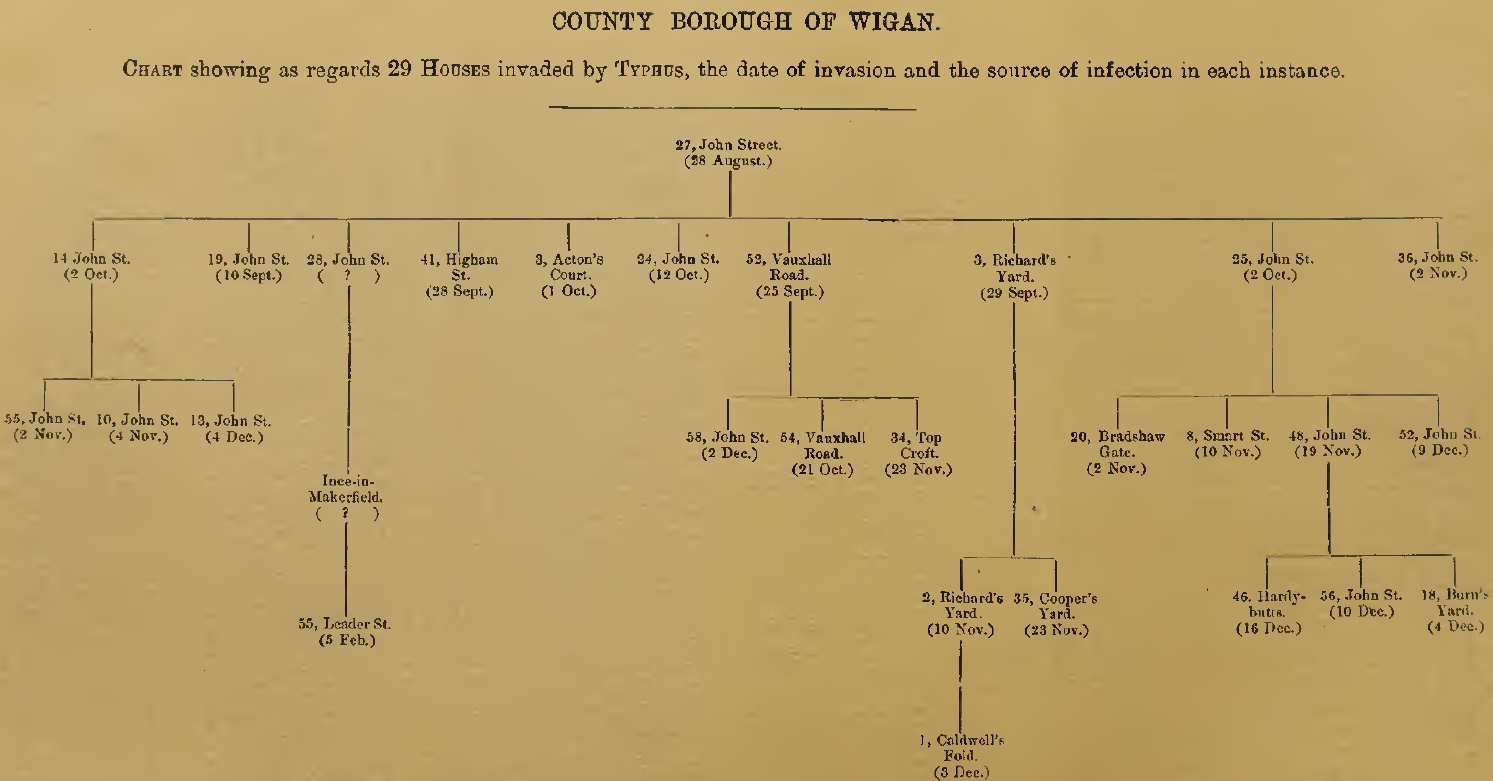

Month by month from the commencement of the typhus, the family invasions, the attacks, and the deaths in Wigan were as follows:—

and the ages at attack and at death were:-

The first official intimation of this outbreak of fever was received on September 24, 1891, while no less than nine cases found to be typhus were removed to the sanatorium during the next two days from a house in John Street, and from one in Vauxhall Road. As all these persons had, a short time previously been living together at 27, John Street, it was obvious that they must have become infected from a common source. On due inquiry being instituted by the Sanitary Authority’s officers it appeared that a boy aged 16 (Edward Woosey) had been seriously ill in a back-to-back house at 27, John Street, a week or two previously ; and on looking through the notification records it was found that this case had been certified as one of pneumonia on September 2nd, on which day he was received into the sanatorium. He had been first seen by a medical man on August 28th, at which time he was said to have been ill for rather more than a week; and from this date until 2nd September he was treated at home. Later on it became obvious that his primary disease had been in reality typhus.

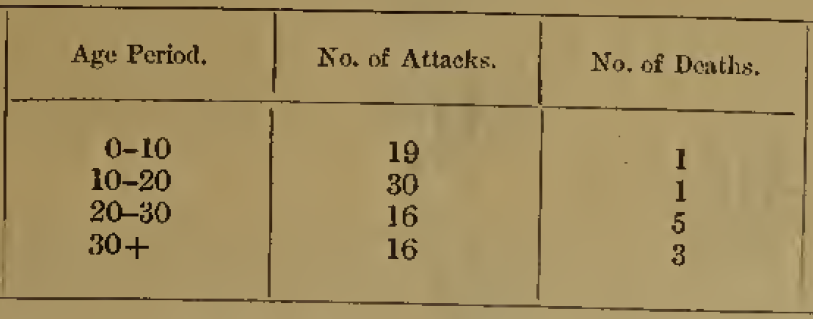

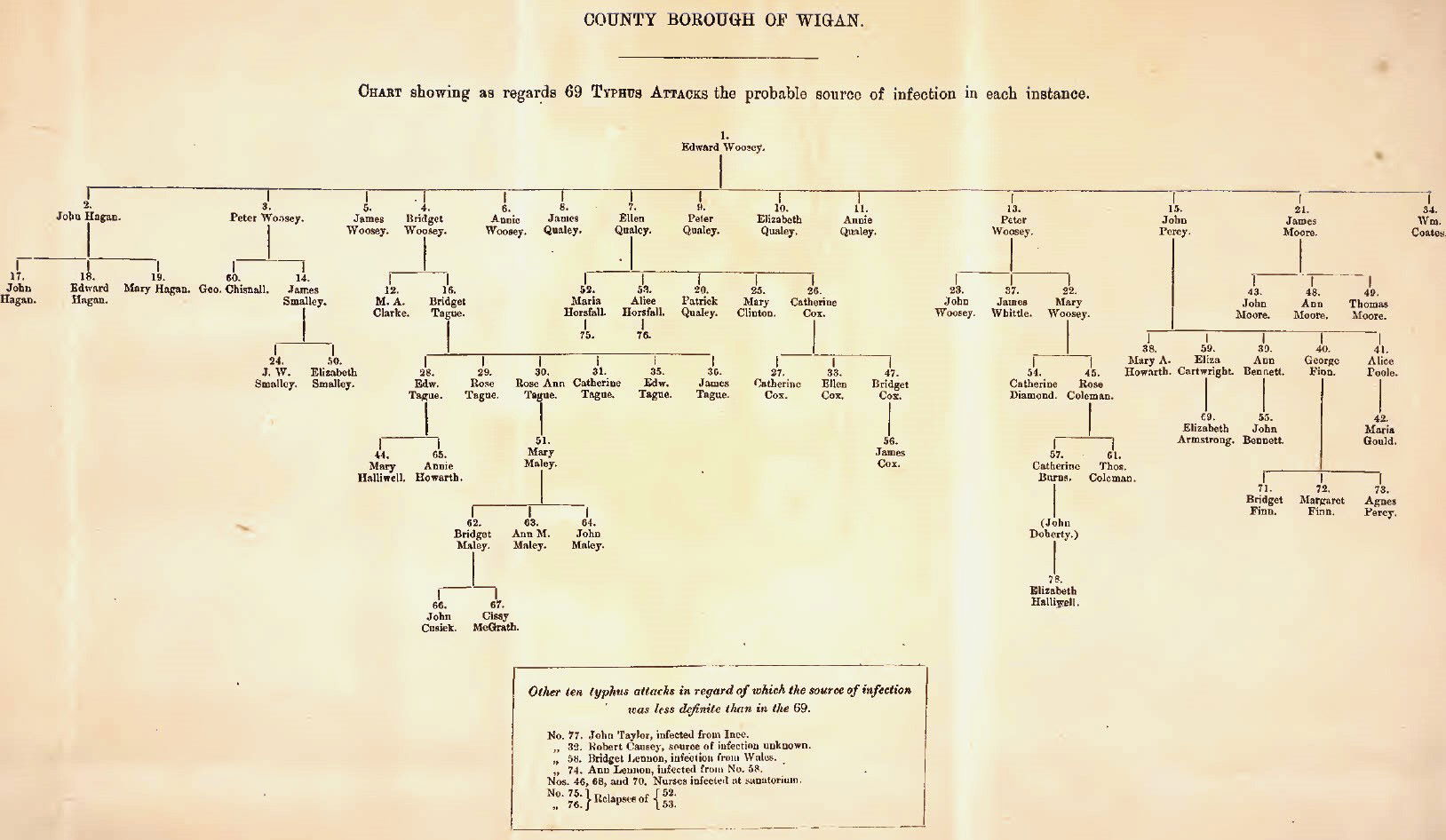

Thereafter every single household invasion, with one exception was traceable directly or indirectly to the Woosey family, as is illustrated chronologically in the following table of the descent of the infection, household by household; and as will be found set out in detail in the appendix where are given abstracts of the records of the health office and an additional chart showing the inter-relation of the several cases.

Fortunately, for the town compulsory notification of infectious disease had been in operation since 1888, and in consequence the officials of the sanitary authority received information of each case of the fever almost, as soon as it occurred. Affected houses were at once visited, and patients removed to the sanatorium, where they could be effectually isolated. This building, which has recently been erected and which is situate about one and a half miles outside the town, consists of an administrative block and two completely separate pavilions, each containing several separate wards. These three blocks stand in about three acres of ground, at one corner of which is a smaller block containing laundry, mortuary, and other outbuildings. During the recent epidemic, when it appeared that the accommodation was likely to be tested somewhat severely, an iron pavilion, containing two wards, with nurse’s room and kitchen, was also erected, so that it is now possible, if necessary, to deal with several different diseases, cases of each of which would be completely isolated from the others. It should here be mentioned that there had been a considerable amount of local opposition to the cost of erection and maintenance of this sanatorium, and party feeling ran so high just previous to my visit that the chairman of the sanitary committee (Mr. Phillips), a warm advocate for possession by the town of adequate accommodation for the isolation of infectious diseases, had been burnt in effigy in the market place. I learnt, moreover, that the building has been commonly known as “ Phillip’s Folly.” On paying a visit to the sanatorium, I found that it was in charge of a man and his wife, seemingly excellent nurses and kind and attentive to the patients under them; they have a staff of nurses varying in number. with the needs of the place. Both buildings and grounds appeared to be in good order, the wards are kept warm yet sufficiently ventilated. 1 may add that the plans for the hospital were submitted to the Board previous to its erection, and that the sanitary and other arrangements appeared to me to leave little to be desired.

Before leaving Wigan, I was requested to meet the sanitary committee of the Town Council, in order to lay before them the results of my investigation into the circumstances of the epidemic, and to make any suggestions as to the precautions necessary to be observed in the future. To this request I acceded; and the more readily on account of my desire to bear testimony to the value of the sanatorium, but for the possession of which I felt very strongly that the town would have suffered from the effects of the epidemic much more severely than under existing circumstances had been the case.

I accordingly met the committee at a late stage of my inquiry, on March 17th, and after congratulating them on the manner in which the outbreak had been restrained within comparatively narrow limits, I called their attention to the existence in the town, in a very marked degree, of certain factors which tend to predispose to the invasion by disease like typhus. I referred particularly to the great amount of overcrowding which prevailed in that part of the town called Scholes, and also to the fact that since a large number of houses in this area are built back-to-back, it has been impossible to secure anything like efficient ventilation of them. In addition, I pointed out that dirt and destitution appeared in this district to be all but universal. Referring also to the fact that in the first house attacked, no less than 11 cases had occurred, I stated that in my opinion, the reason that the outbreak did not afterwards spread in anything like a similar rate was twofold. Firstly, that efficient provision had been made beforehand for isolation of cases of infectious disease, and secondly, that such provision was promptly made use of, by the removal to the sanatorium of every case as soon as it was notified. I further called attention to the fact, that although the disease had, at that time, apparently been stamped out, vigilance was not to be relaxed, as it was possible that the disease might yet break out afresh, particularly in the autumn, at which time it is especially liable to occur.

There remains to be noticed the question of the source of infection of the first case in the Wigan Urban Sanitary District, the nature and source other continued fever occurring about the same time in other parts of the Registration District, and certain clinical considerations arising in connection with the typhus prevalence witnessed.

Source of the Wigan Typhus. '

Inquiry as to the movements of the boy Edward Woosey prior to the date of his attack, elicited the information that he had never done any work since leaving school. I learnt also that he was in the habit of spending a good deal of his time at the canal wharf at Ince, which is a short distance only from the part of Wigan in which John Street is situated. The possibility, therefore, arose of his having come in contact with a previous case of typhus on one of the canal boats, or even of his having taken a trip on one of them to Liverpool, where this disease is known to be more or less endemic. As it appeared at this time quite unlikely that he could have contracted the disease in Wigan itself, where no previous case had been known to have occurred for more than 20 years, I thought it advisable to follow up the suggestion thus afforded, and with this object in view I paid a visit to Liverpool.

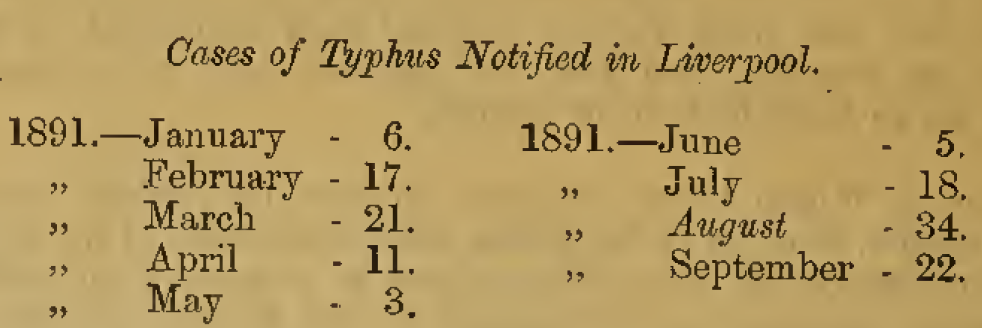

Arrived there, I met, by appointment, the Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Stopford Taylor, who afforded me all the information in his power. On referring to the monthly records of zymotic disease in Liverpool, we found that the number of cases of typhus notified during the year 1891, up to the time of its first appearance at Wigan, was as follows :—

The largest number in any one month had, as is thus seen, appeared in August, particularly in the first fortnight of that mouth, just prior to the occurrence of the first case of the series in Wigan.

Dr, Taylor also supplied me with a map of the city, on which was shown the locality where each case of typhus had occurred during the period of June 1st, August 31st, 1891. Of the whole number notified during that time no less than 18 had broken out in a court off Warwick Street, in Toxteth Park, Liverpool. On making inquiry as to whether this disease had appeared on any of the canal boats, I learnt that such had not been the case. Typhus had, however, we found from the records, appeared in a house close to the canal terminus, the patient in this instance being the daughter of one of the sanitary inspectors, whose duty was to remove cases of disease from infected houses. Notification of this girl’s attack was received on July 28th 1891, when she was immediately removed to the isolation hospital. Further, Dr. Taylor advised me to make inquiries at Bootle and Ormskirk as to whether there had been any recent cases of typhus at either of these places, through both of which the canal runs between Liverpool and Wigan. He also informed me that there had been a death from this disease at Bootle during the third quarter of 1891, and that therefore there might possibly have been several non-fatal cases also.

I paid a visit, therefore, to Bootle, where I called on the Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Sprakeling, but, unfortunately, failed to see him. He, however, was good enough to write to me later on, when he stated that Dr. Taylor had been mistaken to a death having occurred there from typhus as there had been no case of the disease in his district for some considerable time past.

Having to return at once to Wigan, I did not visit Ormskirk on this occasion; nor, indeed, did I do so at all, such a course subsequently appearing to be unnecessary. ’

For on reaching Wigan once more, I learnt from the Inspector of Nuisances that the police had afforded some information which threw valuable light on the manner in which young Woosey had probably contracted infection. ‘It appeared from their evidence, that about the middle of August a navvy, whose name was unknown, had come from Liverpool to work on the railway at Wigan, and that he had lodged at 27, John Street, with the Woosey’s. It was stated also that he was not well when he arrived, and that he became progressively worse during the next week, when, although very ill, he left with the intention of returning to Liverpool if possible. During his stay in John Street, he slept with young Woosey, who was also in his company to a greater extent than other members of the family. Up to the time of writing, I have unfortunately failed in the attempt to trace the further movements or learn more as to the history of this man who was in all probability the primary cause of the outbreak of typhus in Wigan.

Other Fever in the Registration District of Wigan.

At an early period of my inquiry, I heard that there had been one or more cases of typhus at Ince-in-Makerfield, an adjoining township and practically a suburb of Wigan. By certain persons it was thought possible that typhus infection might have been introduced to Wigan from this quarter, but further inquiry sufficed to show that although in one sense this was true, yet in the first instance infection had apparently spread from Wigan to Ince and not vice versa. The facts, as I obtained them with the help of Mr. Hall, the Medical Officer of Health for the Ince Urban Sanitary District, and other persons, were as follows:—A woman named Bridget Taylor, aged 51, had been living with her two daughters. Kate aged 20, and Alice aged 18, at 9, Victoria Street, Ince. Somewhere about the 20th January 1892, the mother was taken ill of what was called “ fever” and afterwards died on 1st February, but it was not possible to find out the nature of the disease which had brought about the fatal termination. On January 27th or 28th, the two daughters were also found to be ill and removed to the local isolation hospital, where typhoid fever was diagnosed ; but apparently their temperatures were not taken regularly, and I was therefore unable to gain confirmation of such diagnosis from temperature charts. Very, shortly after these two girls were taken ill, John Taylor, aged 21, a cousin of theirs who had been lodging with them, went away to Wigan and took up his abode at 55, Leader Street. On February 5th he was found to be suffering from typhus, of which there had been no previous cases in Leader Street, and was removed to the sanatorium. It is, therefore, perhaps a fair inference, that the disease, which had previously attacked his cousins and aunt was also in reality typhus. Later on, it transpired that there had been another woman in the house occupied by these people at Ince for a week or so prior to the date of their attack. This woman, by name Marcella Lawless, had been lodging previously at 28, John Street, Wigan, but about Christmas she went over to Ince with the intention of living for a time with a son of hers, but he, for some reason or other, refused to take her in. She therefore took up her abode with the Taylors, and five days after doing so was taken very ill, when she was attended by a Dr. Parker for ‘‘bronchitis.” Although there had not apparently been a case of typhus at 28, John Street, the disease had existed in many other houses in that street for some time before she left, and consequently it is by no means improbable that she, too, suffered from an attack of what was in reality that disease, as it is very difficult on any other hypothesis than by infection through this woman to explain the subsequent illness of the Taylors, more especially the undoubted attack of typhus in their cousin.

Another reputed Ince case occurred in the person of Elizabeth Halliwell, who was removed from the Wigan Union Workhouse to the sanatorium in consequence of an attack of typhus on March 4th, 1892. She had, at date of attack, been for several months an inmate of the workhouse. At Christmas last, she had indeed discharged herself for a couple of days, and had visited Ince in the interval, but having regard to the customary incubation period of the’ disease, the possibility of her having contracted infection during the brief period for which she left the house may certainly be dismissed. I therefore carefully searched the visitors’ book, and also the admission book, to see whether she could have come in contact at the Workhousc with some person from any of the affected neighbourhoods between the date at which she last entered the house and that at which she was found to be suffering’ from typhus. I also questioned the officials as to what work she had been doing; in reply to which I was informed that she washed the clothes and sheets of patients in the workhouse infirmary. After much futile inquiry I found that among other patients for whom she had washed, was a man named John Doherty, who was admitted to the infirmary on January 30th,1892, said to be suffering from pneumonia, and had died on the following day. It appeared that he had been ailing for four days, and further, that he had come from a house in Caldwell’s Fold (No. 1), in which he had been lodging for some time. Cases of typhus had been removed from this house on December 3rd, and December 6th previously, while from the same house, also, two children aged ten years and seven years respectively had been taken to the sanatorium, the disease notified in these cases being “ continued fever.” Dr. Barnish, however, informed me that there could be little doubt that these were really cases of typhus also. It may here be stated that subsequent to Halliwell’s removal to the sanatorium, no further case of the disease has broken out in the workhouse.

"While at Ince for the purpose of investigating the nature of the “ fever ” from which the two girls named Taylor had suffered, as already described, I thought it desirable to pay a visit of inspection to the local isolation hospital in which, as I was informed, they had been treated.

The hospital is situated in the midst of a large space of waste land known as Amberswood Common, about a mile from Ince. Isolation is thus effectually obtained, but the situation has its disadvantages, since in bad weather the place is exceedingly difficult of approach owing to the practical absence of roads to it. At the time of my visit snow was on the ground, and as a start was made from Ince, I heard strict instructions given to the driver to keep in the direction of the track, lest our vehicle should be overturned. Arrived at the hospital, I found it in charge of an elderly woman and her daughter. The former was apparently deaf and also confined to her chair with rheumatism, while the latter attended to the household duties. Neither of them, as far as I could learn, had had any experience of nursing previous to their appointment. There were no patients under treatment at the time of my visit.

The hospital was built, as I was informed by the clerk to the local board, about 10 years ago. About three years previously, Dr. Parsons, in a report on the general sanitary condition of Ince-in-Makerfield (1879), had made, among others, the following recommendation;—Some provision should be made for the isolation of infectious disease. This should not be delayed until another epidemic has actually broken out, as the chief use of such accommodation is to isolate the first cases of disease, and thus prevent it from gaining a footing in the-district. In consequence of this recommendation it was, after some time, determined to build an isolation hospital on the site I have described, so as nominally to provide for the needs of the district in this respect; but since it was also decided, as the clerk informed me, to cut down the cost to the lowest possible limit, the result can hardly be described as satisfactory.

The greater part of the hospital building consists of two wards, built “ back-to-back,” which communicate at one end with what may be called the administrative portion of the block. Built on to the opposite extremities of the wards are two closets with pent-house roofs. To each of these light is admitted by a small aperture about 5 inches square in the roof. Cross ventilation of the closets is said to be provided for by the insertion of perforatcd bricks on opposite sides near the roof. The wards are whitewashed internally ; the windows and fireplaces are small and ventilation is imperfect. There was also at the time of my visit a considerable accumulation of dust and filth on the top of a wooden lobby by which the ward is entered from the other rooms. The kitchen is used as a living room by the caretaker and her daughter, while what is called the “ waiting-room” is utilised as an extra bedroom.

A few yards from the hospital is a small brick building, half of which is used as a wash-house, while the other half is termed the mortuary. This latter I was unable to inspect as the key had apparently been lost.

It remains to be noted that while at Wigan I made inquiries, in accordance with instructions, as to the occurrence of “fever” in other sub-divisions of the Wigan Registration District, visiting some of them in person. Although in one or two sanitary districts cases of so-called “ continued fever ” had been notified, in no instance, other than those to which I have already drawn attention, could I obtain evidence that any of the patients in question had suffered from unsuspected typhus fever.

Appendix

The following brief history of the progress of the epidemic is mainly based on information supplied to me by Mr. John Sumner, Chief Inspector of nuisances for the borough of Wigan. He stated that the first intimation of the epidemic received, was a personal notice to himself on September 24th last, that “ fever ” existed at No. 27, John Street. He at once proceeded there and found that the tenant, Woosey, his wife, and two children were ill, and were being attended by the Union Medical Officer, who notified the cases next morning as typhoid fever. Mr. Sumner discovered that another boy of Woosey’s (Edward) had been ill for two or three weeks, but appeared at that date all right again. It was afterwards found that this case had been notified on the 2nd September as pneumonia.

On September 10th, John Hagan, of 19, John Street, a playmate of Edward Woosey’s, had been notified as suffering from typhoid, and had been sent into the sanatorium the following day. Woosey’s family, with the exception of Edward, had been taken ill nearly at one and the same time, and they had been ill about three or four days when the inspector first visited them.

In addition to Woosey’s family, Mrs. Qualey and four or five of her children lived also at No. 27, John Street. They were lodgers there, and when they found fever in the house, removed to 52, Vauxhall Road. The inspector immediately informed the Medical Officer of Health of the cases at 27, John Street. He accordingly visited the houses the next day (September 25th), and directed that Woosey, his wife, and their two children should be removed to the sanatorium at once.

The boy, Edward Woosey, who had been ill and recovered, went to stay with his aunt at 3, Richard’s Yard, together with another brother (Peter) who had not yet been ill. The latter was afterwards attacked, and was taken to the sanatorium. When all the tenants had left Woosey’s house, all the bedding and the whole of the furniture, such as it was, was destroyed, and the house was thoroughly disinfected. Whilst the Wooseys were being removed to the sanatorium, the inspector received information that the Qualey’s had been taken ill. He went to their new lodgings at 52, Vauxhall Road, occupied by Mrs. Cox, and found that Mrs. Qualey and her children, with the exception of one boy. were ill.

He notified the fact to the Medical Officer, and on the following day, September 26th, Mrs. Qualey and the four children were taken to the sanatorium. The other boy remained with Mrs. Cox, at 52 Vauxhall Road. After the Qualey’s had been transferred to the sanatorium, Mrs. Cox was induced to remove to another house for a day. Whilst she was away, No. 52 was thoroughly disinfected, and the bed which had been used by Mrs. Qualey, was destroyed. After the house had been fumigated, Mrs. Cox, her family and the boy Qualey returned,

On September 28th, the Medical Officer of Health received a notification that Mary Ann Clark of 41, Higham Street, a friend of Mrs. Woosey’s, was suffering from typhoid. She was removed to the sanatorium the same day, when the case was found to be one of typhus. She was a married woman, living with her husband and child, neither of whom were affected. The house was disinfected the same day. •

On September 29th, Peter Woosey, who had removed from 27, John Street to 3, Richard’s Yard, was notified as suffering from typhus, and was removed the same day to the sanatorium.

October 1st, James Smalley, of 3, Acton’s Court, was certified to be ill with typhus, and was removed to the sanatorium the same day. He was an acquaintance of the Woosey’s.

On October 2nd, John Percy, of 14, John Street, and Bridget Tague, of 25, John Street, playmates of the young Woosey’s, were removed to the sanatorium, suffering from typhus, and on October 5th, John Hagan, of 19, John Street, father of the boy removed on September 11th, with his son and daughter (playmates of Woosey’s), were also removed. ' On On October 12th, James Moore, another playmate of the Woosey’s, was removed to the sanatorium. On the same day Patrick Qualey, who, since the attack of the other members of his family had been living with Mrs. Cox at Vauxhall Road, was taken ill and also removed to hospital.

On October 16th, Mary Woosey (aunt of Peter Woosey, junior), and her son, living in Richard’s Yard, were taken ill and were removed to the sanatorium.

On October 21st, Mary Clinton, of 54, Vauxhall Road, to whose house the Cox’s removed whilst 52, Vauxhall Road was being disinfected, was taken to the sanatorium suffering from typhus. She had been in the habit of visiting Mrs. Cox, who, on October 22nd, was certified as suffering from pneumonia. Mrs. Cox died shortly afterwards, and when the house, 52, Vauxhall Road, was visited it was found that preparations were being made for holding a wake on her body, but with the assistance of the police the friends of the deceased were induced to dispense with the function.

On October 26th, Mrs. Cox’s daughter was removed to sanatorium suffering from typhus.

On October 31st, Mr. and Mrs. Tague and two children were removed from 25, John Street, all affected with typhus; and on the same day Robert Causey, of 215, Scholes, who had previously, from the 8th September to October 25th, been in the sanatorium with scarlet fever, was taken there again suffering from typhus. No. 215, Scholes was disinfected and no further case occurred there.

On November 2nd, William Coates, of 20, Bradshawgate, the only one of a family of eight, who caught the disease, was removed to the sanatorium. He was a friend of the Tague’s, of which family on the same day two more were admitted to the hospital.

Mary A. Howarth, who had been lodging at 55, John Street, with a daughter of John Percy ; A boy (Whittle), of 36, John Street; and another daughter of Catherine Cox, were also all admitted on November 2nd. No other member of Whittle’s family caught the disease.

On the 3rd November, Ann Bennett, of 55, John Street, a married sister of John Percy, was removed to the sanatorium; and the same day George Finn, who had been lodging with her. John Percy at 14, John Street, was also moved to the sanatorium, where he died.

On November 4th, Alice Poole, of 10, John Street (a friend of the Percy’s) was removed to hospital; and on the following day her mother, Maria Gould, was also admitted to the sanatorium.

On November 5th, John Moore, of 24, John Street, father of the James Moore previously mentioned, was removed to the sanatorium.

On November 10th, Mary Halliwell, of Stuart Street, a daughter of Mrs. Tague, was taken to the sanatorium; and on the same day Rose Coleman, of 2, Richard’s Yard, who had been attending the patients next door (at No. 3), was attacked with typhus and sent to the sanatorium. Her son and sister were also attacked at a later period.

On November 10th, Eliza Kelly, nurse at the sanatorium, was taken ill with typhus. Between November 14th and November 19th, Bridget Cox, daughter of Mrs. Cox deceased, was removed to hospital from 52, Vauxhall Road; Ann and Thomas Moore were removed there from 24, John Street; Elizabeth Smalley, daughter of James Smalley, was removed from Acton’s Court; and Mary Maley from 43, John Street (directly opposite Woosey’s house).

On November 23rd, Maria and Alice Horsfall, daughters of Mrs. Horsfall, of 34, Top Croft, a fish hawker, were removed to the sanatorium. Mrs. Horsfall had been very intimate with the Qualeys, but she herself was not attacked.

On the same day Catherine Diamond, of 36, Cooper’s Yard, Scholes, a relative of the Woosey’s, was also removed to the sanatorium.

On December 2nd, John Bennett, of 55, John Street, whose wife had previously been affected, and James Cox, who had removed from Vauxhall Road to 5S, John Street, were taken to the sanatorium, where the latter died.

On December 3rd, Agnes Percy, a sister of Mrs. Finn, was removed to hospital, as was also Catherine Burns, of 1, Caldwell’s Fold, a sister of Rose Coleman, of 2, Richard’s Yard.

On December 4th, Bridget Lennon, whose mother was lodging at 49, Clayton Street, was admitted to the sanatorium, suffering from typhus. This family was stated to have come from Cardiff or some other place in South Wales, only a week before, 'the house was disinfected, but on the 8th December, another sister (Ann) aged four years, was taken ill and also removed.

On December 4th, Elizabeth Cartwright, of 13, John Street, a playmate of the Woosey’s and George Chisnall, of Burn’s Yard, Vauxhall Road, who had been working with Finn and Maley, were isolated at the hospital.

On December 6th, Thomas Coleman, son of Rose Coleman, who had been living with his aunt (Catherine Burns) at Caldwell’s Fold, and on December 7th and 8th, Bridget Maley, together with her daughter and husband, were all removed to hospital from 48, John Street.

On December 9th, Annie Howarth, of 52, John Street, was admitted to hospital. She appears to be no relation to the Howarth’s of 55, John Street, but had been on intimate terms with several of the previous sufferers from the epidemic.

On December 10th, John Cusick, who had formerly lodged with the Maley’s at 48, John Street, was removed to hospital from 56, John Street, to which house he had gone subsequent to a notice having been served for overcrowding at No. 48.

A week later Cissy McGrath, of 46, Hardybutts, who had had occasion to call at 48, John Street, was admitted to sanatorium.

On December 28th, Catharine Nyhan, a nurse at the sanatorium, was laid up with typhus, and on the same day Elizabeth, a sister of Eliza Cartwright, was removed there.

On January 2nd, 1892, Bridget and Margaret Finn, wife and child of George Finn, were removed from 14, John Street, and on January 12th, Maria and Alice Horsfall, of 34, Top Croft, were again admitted to the sanatorium for a relapse of the disease.

On February 5th, John Taylor was removed to hospital from 55, Leader Street. He had been visiting his aunt and cousins at Ince, at a time when the former, who has since died, was suffering from “fever.”

On March 4th, Elizabeth Halliwell, who belongs to Ince, was taken to the sanatorium from the union workhouse, suffering from typhus.

In addition to those specially mentioned, every house in which typhus had existed was disinfected immediately on the removal of the patients, in some instances the process having had to be repeated three or four times over.

The chronological order of the cases mentioned in the preceding paragraphs, and more particularly their relationship to one another as regards infection from case to case, will perhaps be more clearly understood by reference to the table in the form of a genealogical tree, which is appended.

S. M. C,

Footnote: to read the full report:- Link