History & Renovation of Haigh Windmill

History

In 1838, John Sumner, the proprietor of Haigh Brewery, demonstrated his forward-thinking by requesting William Peace, the Chief Mining agent to the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres, to install a pumping plant. This innovative solution would deliver water from two ponds in a nearby field to the brewery reservoir, which held 56,000 gallons, a month's consumption. Peace's calculations led to the selection of a pump with a four-inch diameter ram and stroke of two feet, a testament to the ingenuity of the technical solution.

Further calculations by Peace showed that a pump of this size working at ten strokes a minute for four days would fill the reservoir. In fact, if a windmill were built to work the pump as he recommended, four windy days a month would suffice. Only a small windmill would be required to lift the water the 36 foot difference in height between the ponds and the brewery tank and there was a model of such a windmill at Haigh Hall. Some time previously, the water in the ponds had been analysed and found suitable for brewing.

The choice of a windmill over a steam engine was not only practical but also a testament to the careful consideration of the project. The proximity of Haigh Hall to the brewery made a smokey chimney from a steam engine undesirable, a concern that was well-addressed. Lord Crawford had already expressed his displeasure about the 'vast column of black smoke' emitted from the brewery chimney. In contrast, a windmill would not produce such smoke, making it a more favourable and practical option.

While a windmill was a practical choice, there were still cost considerations. The 2 inch diameter pipes required between the windmill and the brewery would cost five shillings a yard. In his wisdom, Peace suggested that the pump be installed below ground level to protect it from frost and 'mischievous boys'. This practical approach to the installation further highlights the careful planning and consideration that went into the project.

Nothing came of this scheme, however until June 1845, when Glover, the land agent and clerk of the works in charge of the rebuilding of Haigh Hall and the erection of the many other new buildings on the estate wrote to Lord Crawford as follows:

.....Sumner is about to commence his windmill. It will be 27 feet to the top in height, 13 feet in diameter at the bottom, and 9 feet at the top. I am not aware that Varty mentioned this to your Lordship, but I do not see any objection to the structure for he intends to make it neat.

Since there was a considerable surplus of water it was decided to supply Haigh Hall and some of the houses and cottages on the estate from the brewery reservoir and a 3" diameter lead main, with branches, was laid for this purpose. After 1865, there was also an agreement with the Wigan Coal and Iron Company for a supply of water from the meadow Pit at the North end of Riley Lane whenever the windmill broke down.

In 1872, the Wigan Rural Sanitary Authority was set up under the Public Health Act of 1872. This Authority was charged with providing a public water supply to the householders and industries of Haigh and the other constituent districts.

When this came into being, the brewery took the water it required from the Authority and, after 1895, from the Wigan Rural District Council, so the windmill was no longer required. In any case, the brewery closed before the Second World War, and since then, the windmill has been redundant.

2011 - Renovation of the Mill

For many reasons, windmills have an important place in our lives. Inventions emanating from the industrial revolution brought the mills to great efficiency and semi- automation, the further development of which affects everyone today. As well as their place in social and economic history, mills are a vital part of the history of mechanical engineering and the development of motive power for the processing of raw materials.

Constructed in 1840, the Haigh Windmill (Grade 2 listed) is an unmistakeable landmark in the agricultural fields of the Haigh Hall estate.

The Haigh Windmill has had a chequered history. It was originally designed and constructed to pump and draw water from adjacent ponds and rivers to Haigh Brewery (now demolished), some 500m uphill from the site of the windmill. However, it has now been unused for many years.

Due to its exposed location, the mill suffers from neglect, poor maintenance, and frequent storm damage. It is currently in poor condition and serves only as a significant landmark. The existing sails have many lost or broken timbers, and the brickwork shows extensive areas of failed pointing and spalling. Left unarrested, this decay poses a risk of serious structural failure.

Originally constructed in brick, with a timber roof, the mill underwent a programme of restoration in the late 1970s, and as a result, a new roof was constructed of glass fibre. However, this refurbishment was only ever viewed as a temporary measure and left the mill devoid of its original fantail and of the decking which surrounded the tower.

The Windmill was originally owned by Lord Crawford, who, at the time of refurbishment, transferred ownership to the Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council for preservation for the public good.

Following an application to the Heritage Lottery Fund, a small grant of £50,000 has been made available to fund a modest refurbishment, raise community awareness, and provide better interpretation.

Work began on site in January 2011 and has now been completed.

Historic significance:

Wigan’s’ surprising role in the development of Windmill technology.

Wigan, and indeed the Haigh Estate, has an important but little known place in the development of windmill technology, going back 100 years before the Haigh Windmill was built, with an invention that continues in use today on some modern wind turbines.

Edmund Lee, a blacksmith working at Brock Mill forge on the Haigh estate, was granted a patent in 1745 for a “self-regulating windmill”, and unusually for an English inventor, also secured a Dutch patent for the same invention.

This was one of the first attempts to automate the two most arduous tasks a wind miller had to face – setting cloth on the sails and turning either the whole mill, or its cap, to face the wind. This attempt at automation meant that windmills, in an age before reliable steam engines, could be used for tasks such as draining mine workings without the expense of employing someone to be in constant attendance.

In practice, Lee’s design for the sails would have been unworkable, but his fantail, which turned the cap and sails into the wind, was later tweaked by the great Leeds engineer John Smeaton and others and became widespread throughout England and was used across the world. (Stephen Buckland, “Lee’s Patent Windmill”, SPAB 1988)

From the journal of the Swedish traveller and industrialist Reinhold Angerstein, who visited the area in 1754, it is now known that Richard Melling (who had also been employed at Brock Mill and later went on to survey part of the route of the Leeds-Liverpool canal as well as building cottages and almshouses on the Haigh estate) had built a flour windmill at Upholland (probably the tower which still ex- ists) which used the features of Edmund Lee’s patent, namely the fantail to turn the cap and sails which could be set and furled automatically.

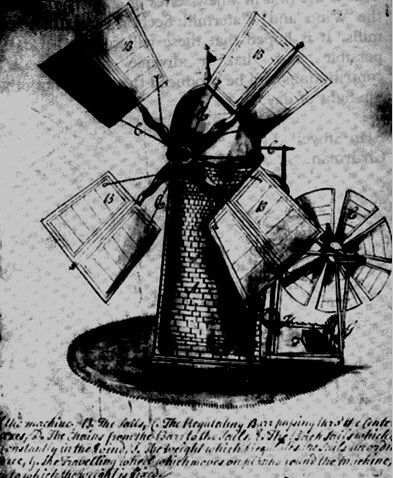

Lee and Melling must have made models of their designs for experimental purposes, and so the reference in Lord Crawford’s mining agent William Peace’s letter of 1838, nearly a hundred years after the patent, to the present Haigh windmill being inspired in part by “a model at Haigh Hall” is tantalising, especially as Lee’s patent drawing shows an unusual, tall, domed cap very like the one on Haigh windmill (see below).

Haigh Windmill is therefore linked to two inventions: to automated windmill sails, and thus to early ideas of automation in general; and to the fantail, the ingenious invention of two Wigan men in the early days of the industrial revolution, which invention had a huge impact on the technology of wind power (and perhaps also did a little to lower the price of coal) but whose local origins have been almost completely forgotten.

Source; Jason Kennedy, ex Wigan Council conservation officer .