Wigan: The Origins of Gerrard Winstanley's Radicalism

WIGAN: THE ORIGINS OF GERRARD WINSTANLEY’S RADICALISM

Prepared for the 3rd Wigan Diggers Festival, September 7, 2013

Gerrard Winstanley is recognized as the foremost radical of the English Revolution. His mid-17th century radical actions and writings have been interpreted as providing a basis for socialism and communism. However, academic researchers generally are at a loss to explain the origins of his radicalism. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that, “The central puzzle remains: how could someone who came from and returned to a conventional, or quiescent, background have articulated a thorough repudiation of the values and institutions of his society, based on a penetrating analysis of its underlying weaknesses?” One leading researcher states that Wiganers had many disputes with the Rector in Gerrard Winstanley’s home town of Wigan, but these “… did not radicalize the townsmen of the borough.” The implication is that Wigan could not be the source of Gerrard Winstanley’s radicalism.

I start by defining radicalism and identifying the views and actions of Gerrard Winstanley that are accepted as being radical. I then apply the same definition of radicalism to the views and actions of townsmen of Wigan and show that these provided a model for Gerrard Winstanley’s radical actions in other parts of the country.

I define radical action as taking measures in revolt against a system of generally accepted or traditional forms that inhibit people’s perceived rights and hamper their development.

Gerrard Winstanley emphasized the importance of learning from personal experience, rather than ingesting what you are told in church and school, or read in books. He was born in Wigan in 1609 and was admitted to the Merchant Taylors’ Company in London in 1630. Apparently, he sailed through a quite privileged life for twenty one years in Wigan and about thirteen years in London and probably had no need to question the spoon that fed him. It was only when he became bankrupt and hit rock bottom in 1647-8 that he took a deep look at himself and the system. My thesis is that it was during his mid-life crisis that he developed a retrospective understanding of his experiences in life. The application of “the inner power of right understanding” led him to him to a penetrating analysis of the socio-economic-political-religious system in England and identification of its underlying weaknesses. Based on his findings, he identified the need for radical change. At the time of his mid-life crisis, more than half of his experience had been in is his home town of Wigan. It is imperative, therefore, to document the experiences in his twenty one years of living in Wigan that could have led to his “enlightenment” and his radical desire to develop collective action to overthrow the lords of the manor and dig common land to demonstrate that the earth is a common treasury for all.

Gerrard Winstanley’s key findings about the state of affairs in England in the mid-1600s are as follows:

- The Creator is righteous and the natural laws of creation make the earth a common treasury and storehouse for all, and give liberty and freedom to all.

- The entire social, political and economic structure of England is unrighteous, immoral and unjust:

- Greed, lust, covetousness, pride, hypocrisy and the use of unjust power by monarchs and lords have taken land from common people by force and murder and they exert unjust power and authority; and

- Monarchs and lords use the church and church leaders to help enforce their illegitimate power and authority.

- The Powers of England have made many promises to make a free nation, but the oppressed poor ─ the majority of people ─ have lost their rights as human beings (dignity, liberty, independence, happiness, wellbeing and the right to vote and participate) and are imprisoned, impoverished, persecuted, oppressed, and enslaved to property owners.

- Organized religion has become a sterile, meaningless body of doctrine and clergy preserve their own riches and esteem.

Gerrard Winstanley sought to overcome grievances by reverting to the natural laws of creation. Key elements of his vision of a new society ─ a free commonwealth ─ are as follows:

- Knowledge of nature and its laws shall be knowledge of God, or Reason ─ a spirit that dwells in each person and whose recognition is born of an inner power of right understanding and personal experience.

- All shall be freemen of the earth and have the right to the free use and enjoyment of the earth and the fruits thereof to meet their needs, starting with the commons.

- There is to be equality of power, liberty, freedom, happiness, representation and opportunity for all men and women.

- Society is to be organized for collective action to secure the welfare and security of all.

In order to determine if there was anything in Gerrard Winstanley’s experience in Wigan that might have served as a model for his radical actions and writings in southern England, I look at what was going on in Wigan 400 years ago. This was long before the Industrial Revolution, when Wigan had a population of just a few thousand. And this is where I turn to the authoritative histories of Wigan and Wigan Parish Church written in the 1880s by Wigan librarian David Sinclair and Rector George Bridgeman. These historians document much that is relevant to understanding Gerrard Winstanley’s experience in Wigan, although neither mentions him.

I first address Gerrard Winstanley’s finding that organized religion had become sterile and meaningless and his rejection of organized religion.

In Wigan, Sundays were holidays, churches empty and “The Parish Church bells only rang to gather the people to their debased and debasing sports.” “As education spread, the human failings of bishops and priests became a part of the popular knowledge and, human like, they and their offices were equally condemned …” Lord Derby lamented “… the sad condition of local irreligion …” and the Rector and the spies of Lord Derby “… came to the conclusion that Wigan was going headlong to the Pope and to ruin, …”. It was widely recognized that “… the Church was the sure path to wealth”, but “Many put on the garb of conformity for the sake of peace and security. There were thousands of wolves in sheep’s clothing.”

The eagle eye of the law took “… cognizance of the attendants, and marked the regularity of the parishioners, judged whether they prayed devoutly and received the sacrament with becoming solemnity.” The Rector "could smell the brimstone about them as distinctly as the most ignorant in his parish. He tormented and persecuted them from no spirit of devilry, but from a candid and conscientious belief that they were the hirelings of sin, and that he himself was a servant of sanctity. Woe to wicked Wigan! Seemed to cry the persecuted zealot.” “As education spread, the human failings of bishops and priests became a part of the popular knowledge and, human like, they and their offices were equally condemned …”.

It was compulsory for Wigan Grammar School pupils to attend church on Sunday and most probably this included Gerrard Winstanley. Gerrard Winstanley stated that he worshipped God, “… but neither knew who he was nor where he was…”

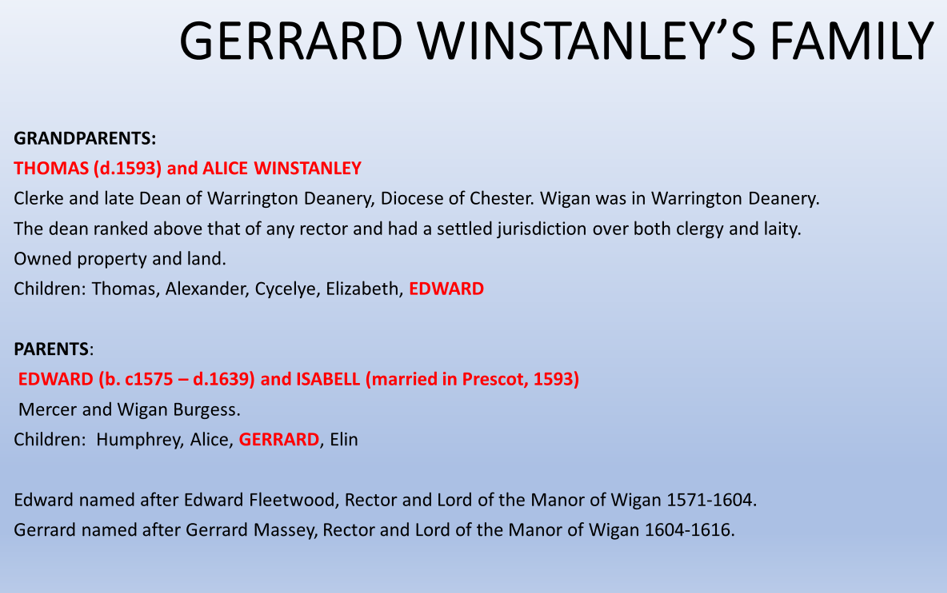

Gerrard Winstanley’s father was Church warden in Wigan Parish Church and gave his son the same name as the Rector, Dr. Gerrard Massie. Whether the Winstanleys were true believers in the Church or wolves in sheep’s clothing is not known. However, Gerrard undoubtedly benefited from his family’s relationships with church officials and benefactors, including most probably being a privileged scholar at Wigan Grammar School and taking advantage of connections to admit him to Merchant Taylors’ Company in London. The Winstanleys who built Winstanley Hall in mid-16th century made their money in the wool and cloth trade in Wales and were well connected to leading national merchants, politicians and aristocrats. Edmund Winstanley, brother of Thomas who built Winstanley Hall, was Steward of Wigan Parish Church at the time that Gerrard Winstanley’s father would have been born. Thus, I submit that Gerrard Winstanley’s finding that organized religion was sterile and meaningless was born of reasoning and appreciation of his personal experience in Wigan; this “right understanding” came later in life, when his world collapsed and he sought to comprehend himself and the world.

In seeking to identify the sources of his radical views about the unrighteous, immoral and unjust structure of England, we can learn much from the history of Wigan.

There was a church in Wigan in Saxon times and people were tied in networks of natural kinship and loyalties and legal obligations of neighbourhood. This changed dramatically with the Norman Conquest in 1066, when all individuals became subservient to the King and Church. The Rector in Wigan then also served as Lord of the Manor and represented the power of the King and Church in Wigan and twelve surrounding townships in the parish. Lords of the manor exerted feudal rights of land ownership and created a community of tenants and serfs – far from the liberty, freedom and equality bestowed on all people by the Creator.

In 1246, King Henry III issued a Royal Charter to Wigan Rector and Lord of the Manor John Maunsell. Maunsell was a member of the King's Council, the first English Chancellor of the Exchequer, Keeper of the Great Seal and Chancellor of St. Paul’s Cathedral. As this Royal Charter is at the heart of contests between Wiganers and Rectors prior to and during Winstanley's upbringing in Wigan, it is important to understand it.

The charter granted borough status to Wigan. Burgesses ─ artisans, merchants and minor gentry ─ were granted authority to establish a merchant guild, which was a group of self-employed, skilled craftsmen, regarded as equals, with ownership and control over the materials and tools they needed to produce their goods. Merchant guilds controlled the way in which trade was conducted in the town.

The charter of freedom to the Wigan burgesses states that the burgesses should have “… their free town, and all rights, customs, and liberties, as is contained in the charter of liberty and acquittance of the Lord King; and that each of them should have to their burgage five roods of land to themselves and their heirs and assigns…” and “… with common of pasture and with all other easements belonging to the said town of Wegan, within and without the town; …” Bridgeman defines easements as “… pasturage in, or firewood to be taken from, the lord’s woods, or other accommodation allowed to tenants, chiefly in respect of roads, water-courses, timber, fuel, stone quarries, or marl-pits …” Burgesses became the free tenants of the Rector and in return for their "freedom" the Rector levied a tithe of twelve pence per year on their 1¼ acre burgages. The Rector's income was dependent on the rents, tithes and produce of tenants and revenue from fairs, markets, fines and mills. Burgesses also had the right to use the resources of the commons, a right not granted to most Wiganers.

The burgesses of Wigan elected two members of Parliament, but the majority of Wiganers – commoners, peasants and labourers – had neither the right to vote nor to serve as representatives. Wigan had a class society with landless laborers and tenants at the bottom, burgesses, a mayor and corporation in the middle, the Rector (and Lord of the Manor) and barons above, and the King at the top. George Bridgeman, himself Rector of Wigan, wrote in 1888 that, as far as he knew, Wigan was the only instance in which secular priests held, in right of his church, such complete powers.

Over the centuries, there were many contests between the Rectors and burgesses relating to claims of ownership of and access to resources (land, pasture, woods etc.), streets and lanes, mills, courts and fairs in Wigan. The burgesses were “… wise enough to see that each one, as an individual had no power against the lords of the land, but they knew that union was strength, …” They “… formed really a well disposed body of unionists determined to stand, or fall, together in defense of right against might.”

By 1618, when Gerrard Winstanley was nine years old, compromise was no longer an acceptable strategy for Wiganers: “… it was now considered a fitting time and proper duty of the Corporation to throw off all allegiances to him [the Rector]”. The Rector at this time was Dr. John Bridgeman, Canon of Lichfield. Wiganers claimed that Wigan did not belong to the Rector and the Rector claimed that the manor of Wigan was his. They elevated their dispute to the King, who appointed four arbiters ─ the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of Ely and two Chief Justices. The four Lords found that Wigan is a manor and ordered that the Rector and his successors should continue to own the manor, including all the wasts (unfarmed common land) and the soil thereof. The four Lords also determined that the freeholders and “all the inhabitants” should have access to and use of the wasts. And “… because the Burgesses are many of them potters, and cannot follow their trade if they should not have liberty to dig clay on the Wasts of the said Mannor, we doe order that it shall be lawfull as well for the said potters as for the parson to dig clay upon the said Wasts: provided that the places so digged be forthwith after the digging sufficiently amended ”. Wiganers did not achieve all their goals, but through collective action, they transformed their disdain for unjust power, authority and organized religion into rights and a degree of freedom. As far as I can ascertain, this was the first time that all Wigan inhabitants – not just the Rector, mayor and burgesses – were explicitly given rights to free use of common land and the fruits thereof.

Gerrard Winstanley identified his own plight with the plight of Wiganers who had lost their rights as human beings and were imprisoned, impoverished, persecuted, oppressed, bereft of meaningful religion and enslaved to property owners. His formative experience in Wigan no doubt revealed to him, in retrospect, the questionable motives and practices of organized religion and public disdain for and contempt of the Church and the almost vice-regal power and abuse of power by the Rector and Lord of the Manor. His “enlightenment” included an understanding of what his experience and upbringing in Wigan really meant to him, what Wiganers struggled for, and how they achieved success.

Probably one of the most memorable events for Winstanley in Wigan was the right that Wiganers earned through radical collective action to dig clay on common land. If Wiganers, through concerted union action, could earn the right to use common land, surely everybody would benefit from the free use of land and the fruits thereof. A much larger digging expedition came to mind and Gerrard Winstanley formed his band of Diggers in southern England.

In 1649 Gerrard Winstanley appealed to Lord Fairfax “… to set us free from the kingly power of Lords of the Manors …” This action is universally recognized by researchers as an expression of radicalism. Surely, then, the same appeal by Wiganers to the King in 1618 must also be regarded as radical. The 1649 Digger pamphlet, “A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England”, was directed “… to all that call themselves, or are called Lords of Manors throughout this nation …” Like Wiganers, The Diggers declared “… That the earth was not made purposefully for you, to be Lords of it, and we to be your Slaves, Servants, and Beggars; but it was made to be a common Livelihood for all, without respect of persons: ...”; “… we have a free right to the Land of England, being born therein…”; and we seek “… a Reformation to preserve the peoples liberties …”. The scope of Gerrard Winstanley’s declaration to Lord Fairfax was national, but I submit that its focus and rationale are indistinguishable from Wiganers’ declaration to the King thirty one years earlier. Winstanley, in brilliant and evocative language, elevated to the national level the demands of oppressed Wiganers for freedom, equality and representation. The actions of Wiganers and Gerrard Winstanley represented revolt against a system of generally accepted or traditional forms that limited people’s activities and hampered their development and their actions were radical.

I agree with researchers that it seems very likely that one spur to radicalism was Winstanley's direct experience of poverty. His intense period of reasoning and search for true knowledge most likely would not have occurred had he continued to be a cloth merchant. However, I go much further and conclude that he probably would not have had the basis for recognizing the ills of England and formulating a vision for a new society had he not received a good education, not experienced for twenty one years the plight of Wiganers, and not understood the strategies that Wiganers applied in struggling for their rights. At the time of his mid-life crisis, he identified his own plight with the plight of Wiganers, who had lost their rights as human beings and were imprisoned, impoverished, persecuted, oppressed, bereft of meaningful religion and enslaved to property owners. In drawing on his experience and the inner power of right understanding Gerrard Winstanley came to realize that Wiganers provided a model for The Diggers

I submit the main reason that Winstanley did not write directly about his family or Wigan was because he did not want to expose his father, probably a burgess and churchwarden, and family to the dangers and possible retribution of associating them with his radical views. The fact that, “… his first written work is dedicated to his ‘beloved country-men of the Countie of Lancaster’, asking them not to despise him for having the temerity to venture into print …” supports this assertion and the importance of Wiganers in his enlightenment.

I conclude that Gerrard Winstanley’s enlightenment occurred in a period of self-discovery, whereby reasoning of the totality of conscious events in his life ─ experience ─ resulted in him understanding reality. To the extent that Gerrard Winstanley is regarded as a founder of socialism, Wigan can be identified as a major source, perhaps THE major source, of his findings, his inspiration for radical reform and socialism.

Derek Winstanley