The Wigan Territorial Force in World War One

- 5th BATTALION MANCHESTER REGIMENT (TERRITORIAL FORCE) 1914-1919

Introduction

As well as relating the stories of family members and other soldiers who served in the regiment, this article focuses primarily on the movements, locations, war time conditions and battles that the first line territorial unit, 1/5th Battalion of the Manchester Regiment fought in during the Great War, from leaving Wigan in August 1914 to its return in March 1919. It also strives to give an insight to the bigger picture, militarily and politically.

In communicating with each other either officially or casually the armed forces use abbreviations, acronyms and nicknames. To anyone who has not served in the military or is not a military researcher this can be baffling and seem like a foreign language. Despite probably being frustrating for anyone who is accustomed to military terminology I have used full titles and terms whenever possible. This is in order for the general user, who for instance might be researching a relative who served in the regiment, to understand the sequence of events more fully without constantly referring to a list of abbreviations.

Much has been written about the exploits of the battalion in the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign of 1915. However, information about their time on the Western Front in France and Flanders from 1917 onward is sparse and has to be obtained from 42nd Infantry Division history records, copies of official orders from Headquarters 127th Infantry Brigade, and War Office trench maps produced by the Ordnance Survey.

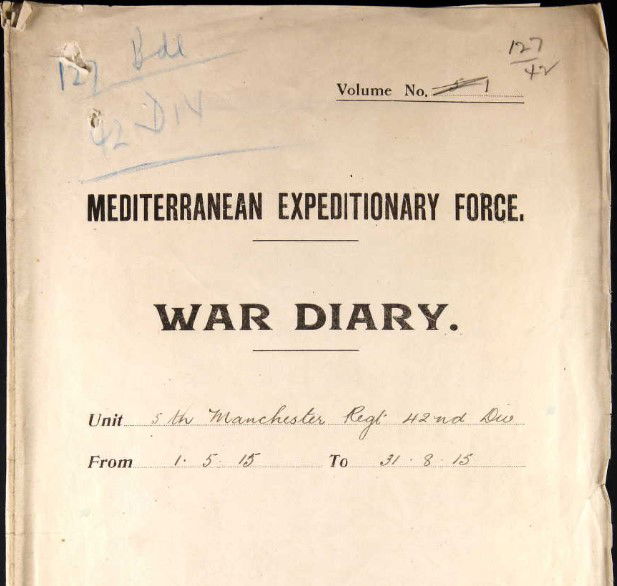

The war diaries were recorded daily, usually by the battalion Adjutant, but sometimes by the Intelligence Officer or Commanding Officer. In total there are 916 daily diary entries available online covering the Manchester’s time at Gallipoli between 1 May and 31 December 1915, and on the Western Front between April 1917 and March 1919, most are written in pencil and some are feint and hard to decipher. The National Archives at Kew hold copies of the diaries covering the battalions time in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine in 1916 and 1917. However these are not available online so details covering that period have been obtained from other written sources.

The very first war diary of the 5th Battalion Manchester Regiment, May 1915

The very first war diary of the 5th Battalion Manchester Regiment, May 1915

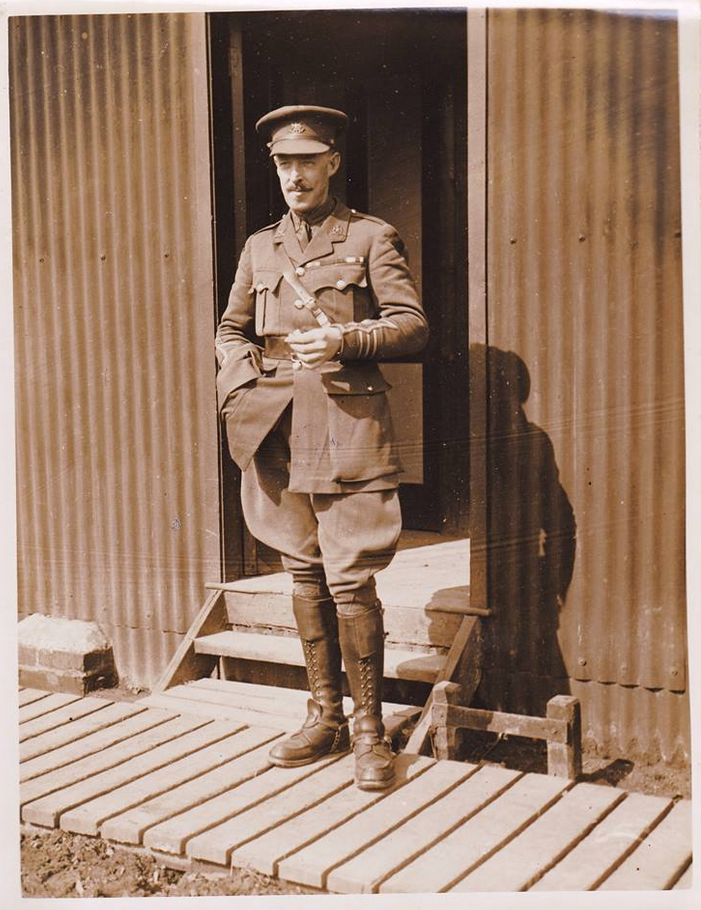

The last war diary entry was made on 28 March 1919 and signed by Lt. Colonel Henry Clayton Darlington, the Commanding Officer who had led the battalion throughout the Gallipoli campaign and onto the Western Front, finally bringing the Regimental Colours home to Wigan in 1919.

Cap badge and shoulder title of 5th Battalion, Manchester Regiment, Territorial Force.

Cap badge and shoulder title of 5th Battalion, Manchester Regiment, Territorial Force.

It is important to note that the 5th Battalion Manchester Regiment raised two more territorial battalions. With the first line troops off to war and the drill halls now empty, more volunteers were recruited in August 1914 to form the 2/5th Battalion, initially made up of territorials from the 5th Battalion who hadn’t signed for overseas service. The battalions’ original intention was to provide drafts of replacements for the first line units serving overseas, however these second line troops were destined to see active service in France and Flanders.

They were assigned to 199th (2/1st Manchester) Brigade), 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Infantry Division, and trained at Altcar Camp near Southport, followed by a move in May 1915 to Crowborough in Sussex. In March 1916 they moved to Colchester in Essex. A year later on 6 March 1917 they sailed from Folkestone to Boulogne on board SS Princess Henrietta to enter the war on the Western Front.

In the press and in local history accounts of the Manchester Regiment, the exploits of 1/5th Battalion in Gallipoli overshadow their second line unit. In fact in twelve months of active service between March 1917 and March 1918 the 2/5th saw plenty of action, taking part in the Battle of Poelcapelle during the Third Battle of Ypres in October 1917 (more commonly referred to as The Battle of Passchendaele). The battalion suffered 98 killed in action, 314 wounded and 23 missing in action between March 1917 and February 1918.

The battalion also suffered very heavy casualties in the German Spring Offensive which commenced in March 1918. At first a composite battalion was made up from remnants of the various companies but the battalion had suffered such heavy losses that the decision was made not to bring the battalion back up to full strength.

In April 1918 they were reduced to a training cadre, tasked with teaching newly arrived American troops the art of trench warfare. The strength of the battalion at the end of June 1918 was twelve officers and 62 other ranks. 2/5th Battalion was officially disbanded on 31 July 1918 at Haudricourt, between Amiens and Rouen in France. The remnants of the Cadre were then transferred to their first line battalion counterparts, the 1/5th Manchester's, who then officially became the 5th Manchester Battalion, although they continued to use the prefix 1/5th in their title.

A new third line battalion designated 3/5th Battalion Manchester Regiment was formed on 20 May 1915. Early in 1916 they moved to Witley Camp, near Godalming in Surrey for training. On 8 April 1916 they became the 5th (Reserve) Battalion, stationed at Codford Camp on Salisbury Plain, training replacements for the other two front line units serving abroad.

On 1 September 1916, the day that National Conscription started, the 5th (Reserve) Battalion Manchester Regiment absorbed the 6th and 7th (Reserve) Battalions and became part of the East Lancashire (Reserve) Brigade. It entailed a move back to Lancashire in October 1916, where they trained at Altcar for three months. The brigade subsequently moved to Ripon in North Yorkshire in January 1917, then three months later to Scarborough, in late 1918 they were at Hunmanby Camp near Filey until disbandment in 1919.

A FAMILY at WAR

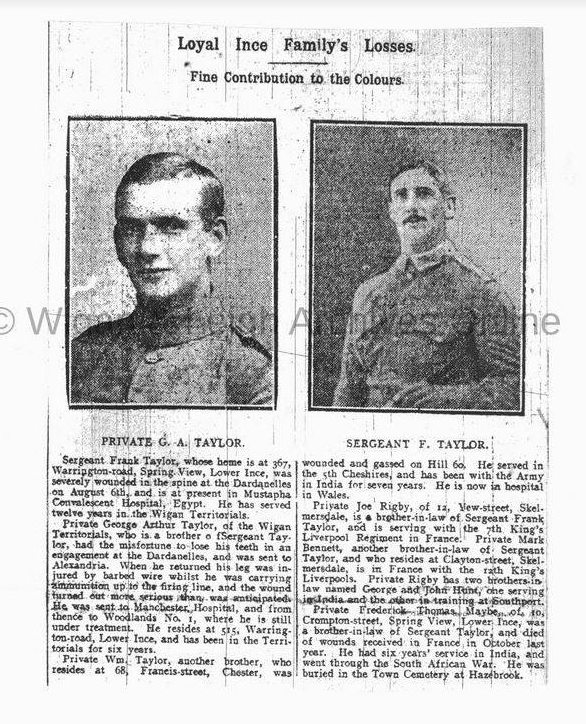

In 1915 the Wigan Observer & District Advertiser published an article about my family, entitled ‘Loyal Ince Families Losses - Fine Contribution to the Colours’ with the accompanying photos of my grandfather Sgt Francis Morgan Taylor and his younger brother, my great uncle, Pte George Arthur Taylor. (from here on referred to as Frank and George). They were both serving in 1/5th Battalion Manchester Regiment (Territorial Force) and had both been wounded in the Dardanelles Campaign.

Wigan Observer & District Advertiser 1915

Wigan Observer & District Advertiser 1915

The article was a regular feature used by all newspapers during World War One, as a way of reporting on local soldiers who had been killed in action, wounded or missing. Information and photos were obtained from families to add more detail to the brief casualty lists. As well as my grandfather and great uncle there were accounts in the article of four other family members who had either been killed in action or wounded and discharged from the army.

6376 Pte Frederick Thomas Maybe

With the Great War just nine weeks old, my great aunt Alice’s husband, Frederick Thomas Maybe had been killed in action in France in 1914, aged 32. A regular soldier, serving with 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, he had served in India for six years and throughout the Second Boer War in South Africa.

He was one of the original ‘Old Contemptibles’, a reference to a remark Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany made when he described the small but professional British Army as that ‘Contemptible little army’. The Germans and French, who had standing armies ten times larger, were more prepared for a European War than the British Army, whose priority was maintaining a world-wide Empire. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of 1914 used this criticism as a badge of honour and were proud to be called the ‘Old Contemptibles’.

1st Battalion North Staffs landed at St. Nazaire on 12 September 1914, then by a combination of train journeys and marching they made their way 440 miles across France to Courcelles near the Belgian border. Ten days later they went into the trenches for the first time, relieving the South Staffordshire Regiment.

Frederick died of wounds suffered in battle on 13 October 1914 and is believed to have first been buried in the French cemetery at Merris, near to the town of Hazebrouck. Like thousands of other soldiers who have no known grave, his final resting place was obliterated as the fighting raged back and forth and whole cemeteries were destroyed in artillery barrages.

There is a memorial cross to Frederick at Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery at Souchez, north of Arras and a mile to the west of Vimy Ridge. It is what is known as a Special Kipling Memorial, with Rudyard Kipling himself choosing the epitaph. On it is inscribed.

‘To the memory of this British Soldier Killed in Action 1914 and believed to be buried at the time in MERRIS Churchyard, whose grave is now lost. Their glory shall not be lost'.

Frederick's name is also inscribed on the war memorial in Ince Urban District Cemetery on Warrington Road, Lower Ince, Wigan.

In May 2000 the remains of an unknown Canadian soldier were taken from Cabaret Rouge Cemetery and buried in a special tomb at the foot of the National War Memorial in Ottawa, Canada. A focal point for remembrance, he represents more than 71,000 Canadians who lost their lives during the First World War. A headstone in Plot 8, Row E, Grave 7 marks the unknown soldier's original grave.

Cabaret Rouge British Military Cemetery

Cabaret Rouge British Military Cemetery

John William Taylor

My great Aunt Mary’s husband, John William Taylor, from Chester was serving in the 5th Battalion Cheshire Regiment. He had been gassed at the strategically important position of Hill 60 (named after the contour line it sat on) at Zillebeke, three miles south of Ypres in Flanders

Hill 60 wasn't a natural feature but man made, it was originally a spoil heap from a cutting following the construction of the railway between Ypres and Menen. The British had captured the hill which had commanding views of the surrounding countryside, by the use of underground mines. with very little losses on 17 April 1915. By 5 May however, after repeated bombardments with gas shells Hill 60 was back in German hands.

Of the 2,413 British casualties admitted to hospital, 227 died. At the time of the article in the newspaper John had been evacuated back to the UK and was currently recovering in hospital in Wales.

Bunker at Hill 60, Zillebeke, Flanders. Originally a German shelter it was expanded and fortified by the Australians in 1918, The bunker also saw heavy fighting on 27 May 1940 during the withdrawal by the British Expeditionary Force to Dunkirk.

Bunker at Hill 60, Zillebeke, Flanders. Originally a German shelter it was expanded and fortified by the Australians in 1918, The bunker also saw heavy fighting on 27 May 1940 during the withdrawal by the British Expeditionary Force to Dunkirk.

14740 Pte Mark Bennett

The husband of my maternal great-aunt Isabella who resided at 39 Clayton Street in Skelmersdale was Mark Bennett of the 12th (Service) Battalion, Kings (Liverpool) Regiment. Mark disembarked at Boulogne with his battalion on 24 July 1915. In 1916 the battalion fought in the Battle of the Somme which lasted from 1 July to 18 November. They were in action alongside the Canadians at Mount Sorrell in June, and Delville Wood in August, they fought at Guillemont, Flers Courcelette, and Morval in September and the Battle of Le Transloy in October 1916, the last big attack on the Somme. In 1917 they were in action during the German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line. That year Mark was wounded in action, suffering a gunshot wound to his right leg. He was discharged from the army on 8 October 1917 with a thirty percent disability assessment, receiving a weekly pension of 17 shillings for his wife and two children.

227598 Pte Joseph Rigby

Also mentioned in the newspaper article was my maternal great-uncle Joseph Rigby who lived at 12 New Street Skelmersdale. He served in the 1/7th Battalion, Kings (Liverpool) Regiment. He entered the theatre of war in France on 5 August 1915 and was wounded in battle on 31 March 1916. After recovery he was transferred to 2/1st Rifle Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment, a territorial unit who were based in Suffolk. He was discharged from the army as being unfit for further military service on 8 June 1917 at Shrewsbury. Before the war he worked as a miner at White Moss Coal Co. Ltd in Skelmersdale.

Part Time Soldiers

My grandfather Frank enlisted into the 1st Battalion Manchester Volunteers in 1903 aged 18. On 1 April 1908, following the reforms introduced by Richard Haldane, the Secretary of State for War, the Territorial Force (TF) was formed by combining the Volunteer Force with the mounted Yeomanry Forces while the Militia was renamed the 'Special Reserve'. Thus 1st Battalion Manchester Volunteers was re-designated as the 5th Battalion Manchester Regiment (Territorial Force).

Colour Sgt Francis Morgan Taylor MSM

Colour Sgt Francis Morgan Taylor MSM

The part time soldiers, nicknamed the 'Terriers', were the butt of jokes and were derided as ‘Saturday Night Soldiers, ‘Saturday and Sunday Only Soldiers’ or as ‘Weekend Warriors’. However when the time came to answer the call to arms they did so with distinction, as they had done so during the Boer War in South Africa fourteen years earlier.

The Territorial Force was originally envisaged as a home defence force for service during wartime; units were liable to serve anywhere within the United Kingdom when the force was embodied (i.e. called up for active service) but could not be compelled to serve outside the country.

However in 1910 the part time soldiers were invited to volunteer to be liable for overseas service by signing Army Form E624, which enforced the Imperial Service Obligation Act. To distinguish them from 'Home Defence Only' soldiers, the ones who signed were issued with a badge, worn on the right breast of their uniform, under the Kings Crown were the words ‘Imperial Service'.

Imperial Service badge

Imperial Service badge

In March 1913 Frank married my grandmother Alice Rigby, who hailed from Skelmersdale, at Wigan Register Office. Their first child Isaac was born later that year. In 1914 Frank worked for Ince Urban District Council as a carter, transporting goods by truck. He simultaneously held the rank of Corporal in the Territorial Force for which he was paid a daily rate of one shilling and eleven pence, which included proficiency pay of three pence.

His younger brother George became a territorial soldier on 13 June 1910 aged 18. At the time he was an apprentice carpenter at W.R. Davies & Co. Railway Wagon Works at Springs Branch in Lower Ince, Wigan. He married Elizabeth Hunt in 1914, just before the start of the First World War.

The Great War

In the summer of 1914 the territorial soldiers had just returned from their Annual Training Camp at Carnarvon in North Wales. They were blissfully unaware that soon they would be fighting for real in a deadly conflict that would claim millions of lives.

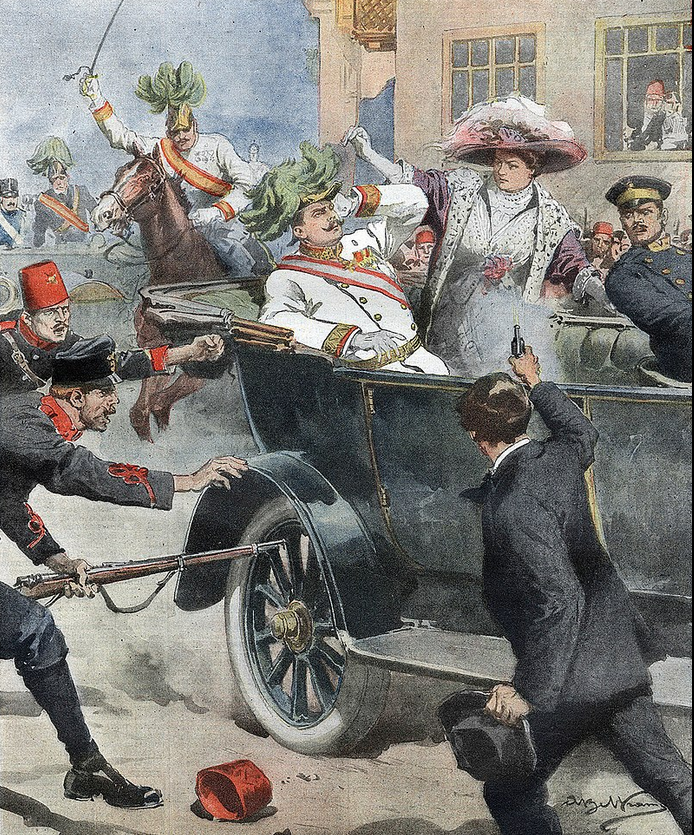

The assassination in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, on 28 June 1914, by Bosnian Serb Nationalist Gavrilo Princip set off a rapidly escalating chain of events that would soon engulf Europe. On 28 July, with the backing of Germany, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, who then appealed to Russia for assistance. Because of the political alliances in force at the time it meant that within a week, Russia, France, Great Britain and Serbia had lined up against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and World War One had commenced.

The assassination of Arch Duke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie

The assassination of Arch Duke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie

On 4 August 1914, Germany enacted the ‘Schlieffen Plan’, an aggressive military strategy that meant invading France through neutral Belgium. Kaiser Wilhelm II thought that Britain wouldn’t intervene as it’s small professional army was busy garrisoning the Empire and had no capacity to provide an expeditionary force in a major war He also reckoned on the German Army smashing through the Belgium defences and taking Paris before their Russian allies could respond.

That same day, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith told the nation that Great Britain was now at war with Germany and her ally Austria-Hungary, for failing to respect Belgium’s neutrality.

Call to Arms

The original 100,000 strong British Expeditionary Force consisted of one army of five regular army divisions in 1914. This would increase to two armies of sixteen divisions with the mobilization of the Territorial Forces.

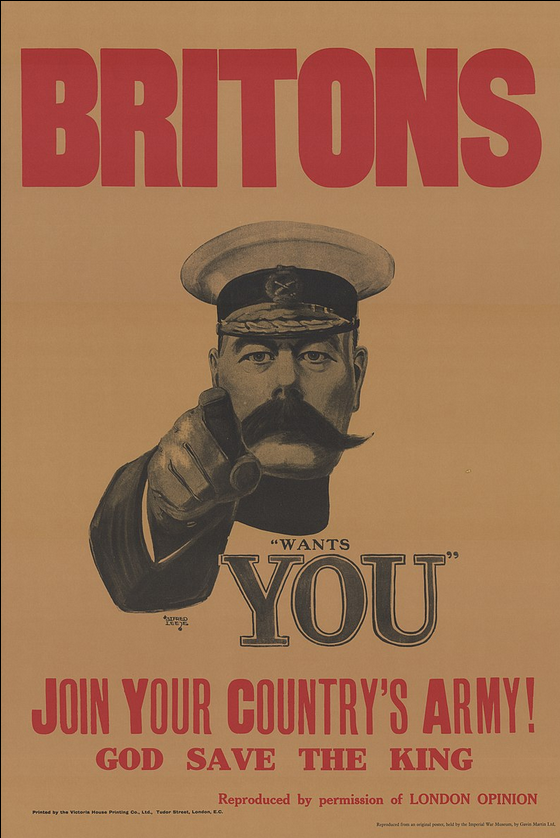

Field Marshall Lord Kitchener the Secretary of State for War immediately started recruiting volunteers for his new army. The concept of the million strong civilian army was born. He planned to have half a million men ready and trained by 1916 but circumstances dictated they be used earlier in 1915 at Gallipoli and the Battle of Loos in France. To distinguish them as New Army troops the newly formed battalions had the word 'Service' in brackets in their title before their Regimental name.

Eventually numbering over five million men, Britain's army in the First World War was the biggest in the country's history. Remarkably, nearly half those men who served in it were volunteers. Nearly two and a half million men enlisted between August 1914 and December 1915. In 1916 the volunteer system ended when national conscription was introduced.

The famous WW1 Lord Kitchener recruiting ad

The famous WW1 Lord Kitchener recruiting ad

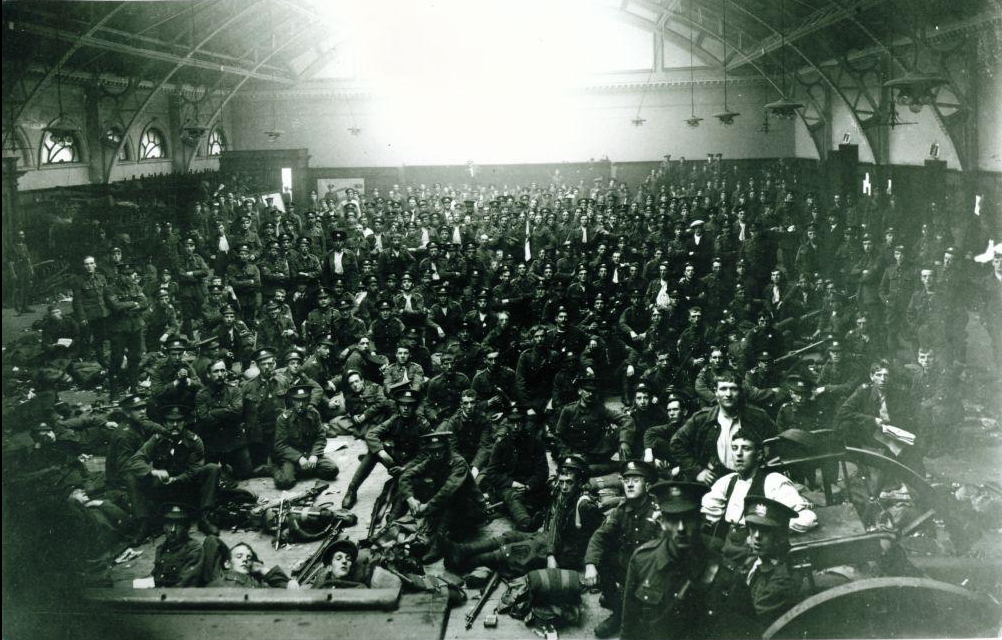

At 1730 hours on 4 August 1914 the Manchester Brigade of the East Lancashire Division, consisting of the Wigan based 5th Battalion and its sister battalions the 6th and 7th in Manchester, and the 8th in Ardwick were mobilised for war. The territorial soldiers were ordered to report with all their kit to their respective Drill Halls.

Volunteer Drill Hall, Powell St, Wigan

Volunteer Drill Hall, Powell St, Wigan

For the first couple of weeks after war being declared, the officers and other ranks remained within easy reach of their headquarters. Originally the Manchester Brigade’s War Station was to be in Ireland, but due to the political and military situation at the time the intended move did not materialise.

The Commanding Officer was Lieutenant Colonel W. S France whose headquarters was at Bank Chambers, located at the junction of Wallgate and Library Street in Wigan. The battalion had eight rifle companies in total. Five of the companies, ‘A’ to’ E’ were based at the Drill Hall in Powell Street in Wigan. ‘F’ Company was based in Eccles,’ G’ Company in Leigh and ‘H’ Company in Atherton.

On the morning of 7 August ‘G’ Company paraded in Leigh then marched to Wigan to muster with the rest of the battalion, ‘F’ and ‘H’ Company's arrived that evening. Apart from the Drill Hall, the troops were billeted in the Wesleyan, St. John’s & St. Mary’s and St. George’s schools.

Troops in Wigan Volunteer Drill Hall, August 1914

Troops in Wigan Volunteer Drill Hall, August 1914

Frank and George along with hundreds of other part time soldiers marched out of Wigan Drill Hall on 20 August 1914, sadly many of them were never to return. The battalion moved to their allotted war station, a tented camp at Hollingworth Lake near Littleborough, to the north east of Rochdale, to await further orders.

On 10 August Lord Kitchener the Secretary of State for War, invited the Territorial Force to volunteer for foreign service. Within a few days the vast majority of the Manchester Brigade had done so. The unit was designated with the number one before the battalion number to indicate that it was now a First Line or Foreign Service unit and thus the Wigan Territorials became 1/5th Battalion Manchester Regiment.

(From now on in the narrative, unless out of necessity, 1/5th Battalion will be referred to as the 5th Manchester's, 5th Battalion, or simply the battalion.

On 2 September, Colonel France was appointed by the War Office to be a General Staff Officer 1st Grade and posted as Assistant Adjutant and Quarter Master General to the East Lancashire Division. His replacement, Major Henry Clayton Darlington was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and took command of the battalion.

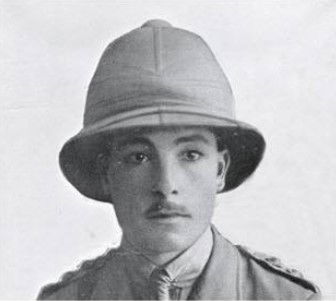

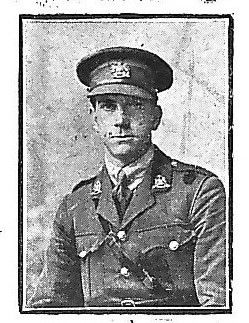

Lt. Col Henry Clayton Darlington C.O. 1/5th Manchester's

Lt. Col Henry Clayton Darlington C.O. 1/5th Manchester's

East Lancashire Infantry Division Order of Battle

The East Lancashire Division (later to become 42nd Division) was made up of three infantry brigades, the 125th (Lancashire Fusilier) Brigade, 126th (East Lancashire) Brigade, and the 127th (Manchester) Brigade.

Each brigade consisted of four infantry battalions. 125th Brigade consisted of 1/5th, 1/6th, 1/7th and 1/8th Battalions of the Lancashire Fusiliers. 126th Brigade consisted of 1/4th and 1/5th Battalions of the East Lancashire Regiments, and 1/9th and 1/10th Battalions of the Manchester Regiment. 127th Brigade had under its command, 1/5th, 1/6th, 1/7th, and 1/8th Battalions of the Manchester Regiment. Each brigade headquarters had under its command a machine gun company.

At the start of the war the British army didn't have any mortars but as these were developed a trench mortar battery was allocated to each brigade.

The East Lancashire Division Headquarters had under its command mounted troops in the form of 'A' Squadron, The Duke of Lancaster's Own Yeomanry, divisional artillery of two Royal Field Artillery batteries, and a battery from the Royal Garrison Artillery who had four 4.7 inch heavy guns. Also under its command was a machine gun company, eventually a heavy trench Mortar battery and three medium mortar batteries were allocated as divisional troops to be used at the discretion of the commander.

An Infantry Division just does not consist of infantry soldiers, but is supplemented by many hundreds of support troops, without whom the division would not function as a fighting force. Eventually the division had under its command three field companies of Royal Engineers, a divisional employment company from the Labour Corps, a Royal Engineers company of signallers, and a divisional train from the Army Service Corps who provided the transport and supply column.

Medical facilities were provided by three Field Ambulances, a mobile veterinary section and a sanitary section. Later in the war as tactics changed the number of battalions in each brigade was reduced from four to three. In February 1918, a pioneer battalion was attached, in the form of 1/7th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers.

Middle East Expeditionary Force

Lord Kitchener had a low opinion of the Territorials and was more concerned with raising a new army. He described the divisions and regiments of the Territorial Force as "a town clerk's army." and thought these amateur soldiers might not be able to hold their own against the German Army. So he decided to send these forces to the peripheral campaigns; to India, the Sudan, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Aden, Malta and Gibraltar therefore releasing regular British Army soldiers for duty on the Western Front. It is estimated that five regular army divisions were created from troops released by Territorial Force deployments.

The East Lancashire Division was warned for movement on 5 September 1914 and on the 9th entrained for Southampton. About forty trains were required to transport men, horses, guns and all the materiel of war. The next day 20,000 Lancastrians, the vast majority of whom had never before left the shores of Britain, embarked on the great adventure. As part of the Middle East Expeditionary Force (MEF) they were the first Territorial Division to volunteer for foreign service and the first ever to leave England’s shores.

The convoy, escorted by HMS Ocean and HMS Minerva consisted of fifteen troop vessels with the Manchester Brigade on board the troopship SS Caledonia. (The Caledonia was later sunk by a German submarine, U65, 125 miles off Malta in December 1916 on route from Salonika to Marseilles).

The division arrived at Alexandria in Egypt on 25 September 1914, before moving to the Cairo area for acclimatisation and training and act as a deterrent to Turkish aggression. One battalion from the division was sent to Khartoum in the Sudan and half a battalion to Cyprus to guard key military installations.

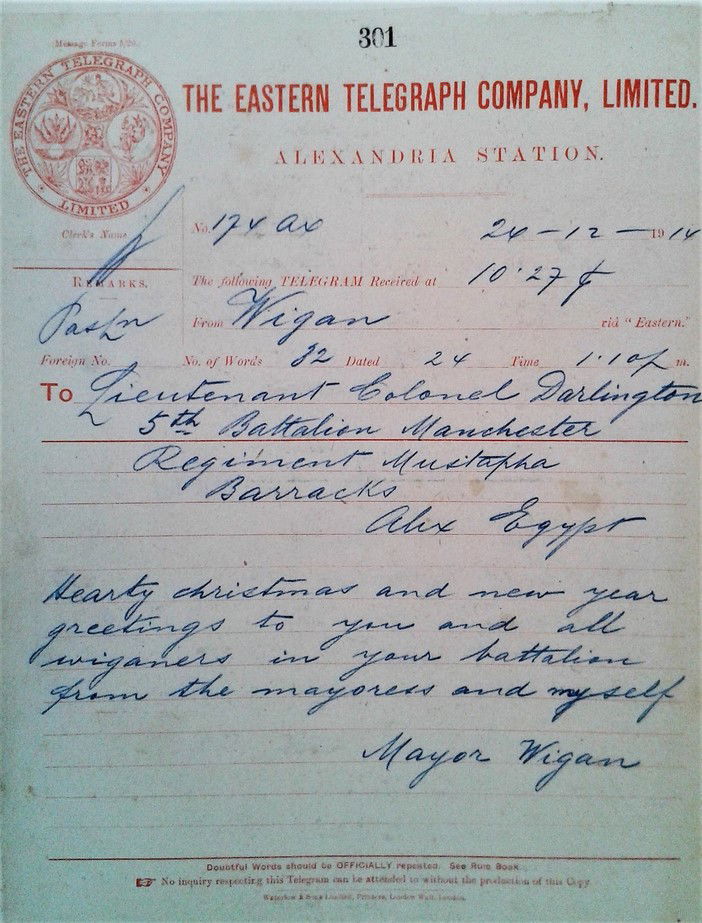

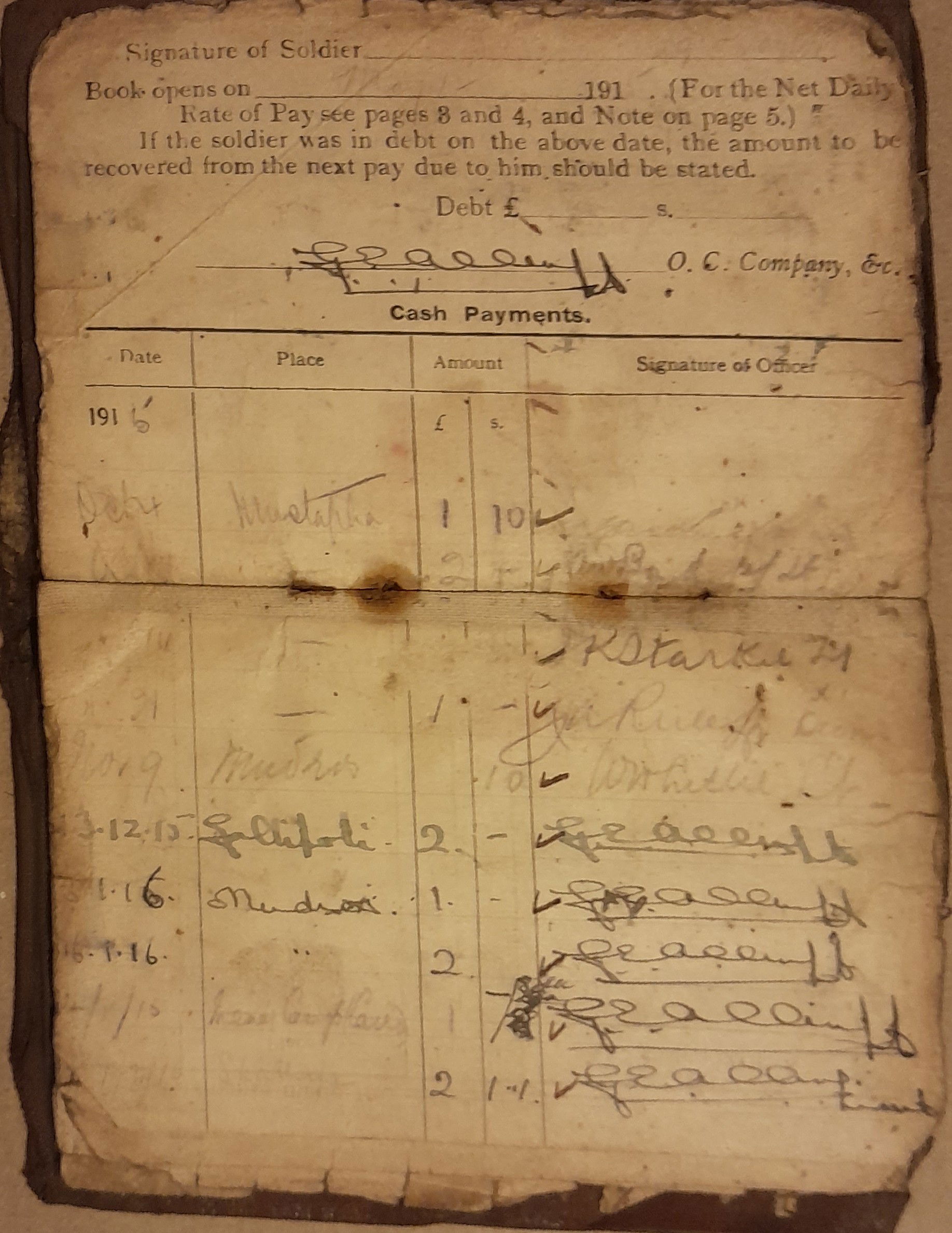

The Manchester Brigade remained in Alexandria as garrison troops and to guard civilians of enemy nationality before their internment in Malta, 5th Battalion was quartered in Mustapha Barracks in the city. On 24 December 1914 Lieutenant Colonel Darlington received a telegram from the Mayor of Wigan, Councillor John Thomas Grimshaw, sending the battalion Christmas greetings.

Telegram from the Mayor of Wigan received 24 December 1914

Telegram from the Mayor of Wigan received 24 December 1914

George didn’t travel to Egypt with Frank and the main body of men but arrived later on 5 November, the same day that Britain declared war on Turkey, turning Egypt into a war zone. On 19th January 1915 the Manchester Brigade moved from Alexandria to Cairo to take over garrison duties.

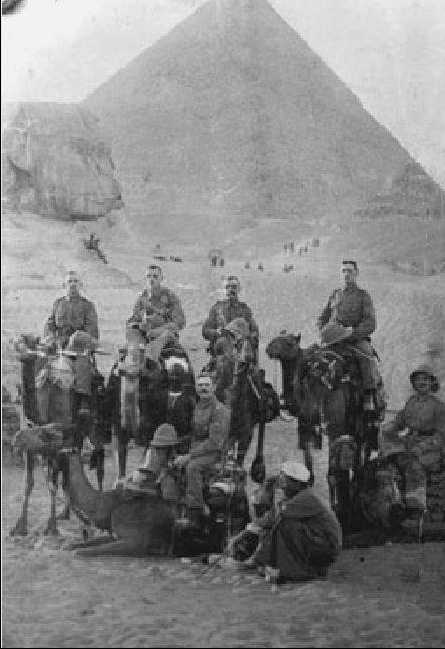

The Manchester's in Cairo

The Manchester's in Cairo

Dardanelles Campaign

The Dardanelles Campaign was an attempt by the Allies to force Turkey out of the war and relieve the deadlock on the Western Front in France and Belgium by opening a supply route to Russia through the 38 miles long Dardanelles Straits at Gallipoli, which divides Europe and Asia. Then on through the Sea of Marmara and into the Black Sea via the 18 miles long Bosporus Strait which divided the city of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul).

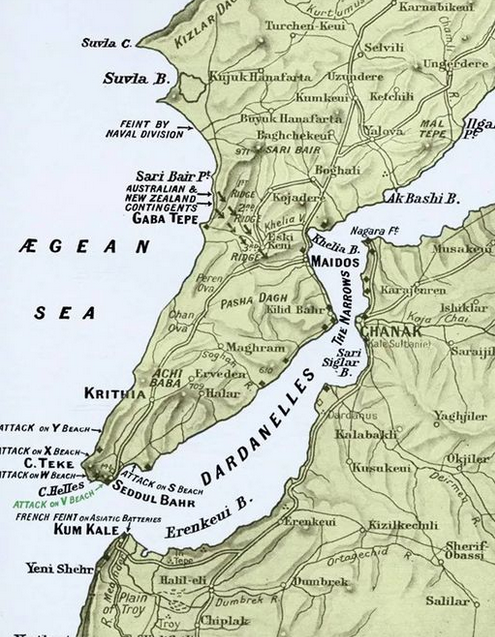

The Dardanelles, Turkey

The Dardanelles, Turkey

With the bulk of the British Army fighting on the Western Front it was originally meant as a naval only operation. On 17 February 1915 a British seaplane from HMS Ark Royal flew a sortie over the Straits. The next day the first attack on the Dardanelles began when a strong Anglo-French task force, began a long-range bombardment of the numerous Ottoman artillery forts along the coast.

However the Allies suffered badly, losing many ships to sea mines and artillery fire, so a decision was made for the army to invade the Gallipoli Peninsula. The invasion force was a hotchpotch of units, British regiments were brought back from India along with Indian troops and Gurkhas. The Anzacs from Australia and New Zealand sailed to the Middle East to join the campaign, also a French contingent joined the Force.

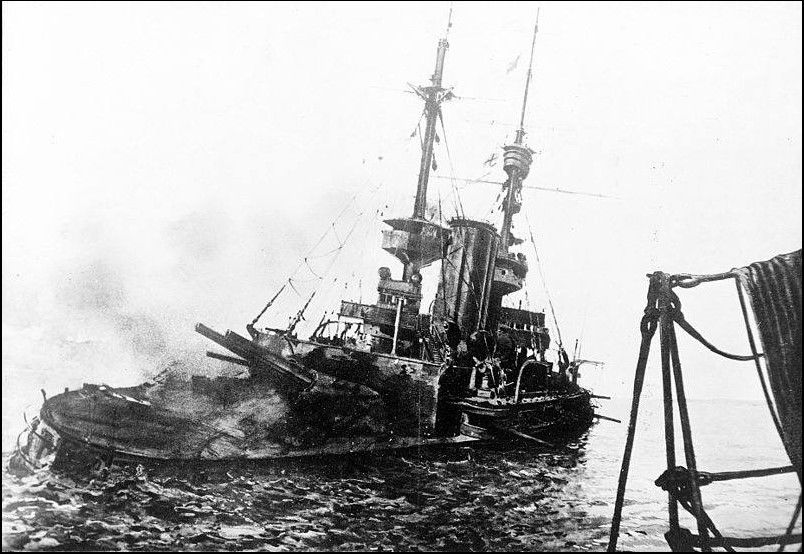

The last moments of HMS Irresistible, sunk in the Dardanelles Straits 18 March 1915

The last moments of HMS Irresistible, sunk in the Dardanelles Straits 18 March 1915

At the beginning of May 1915, the 5th Manchester's were at Abbassia Barracks in Cairo where they received orders for their move to Gallipoli. Frank and George were among thirty two officers and 816 other ranks who embarked aboard the Derfflinger (a German passenger ship belonging to the Norddeutscher shipping line that was captured at Port Said in August 1914). It had just arrived with casualties from the initial landings on Gallipoli.

They departed Alexandria at 1700 hours on 3 May. Whilst en route to Gallipoli Frank made out his will which was on the back page of his pay book. Completed in the standard format recommended, and written in pencil, it simply said:

‘In the event of my death I give all of my property and estate to Mrs Alice Taylor, 367 Warrington Rd, Wigan. Signed Cpl F. Taylor 5th Manch Reg. Dated 4/5/15’.

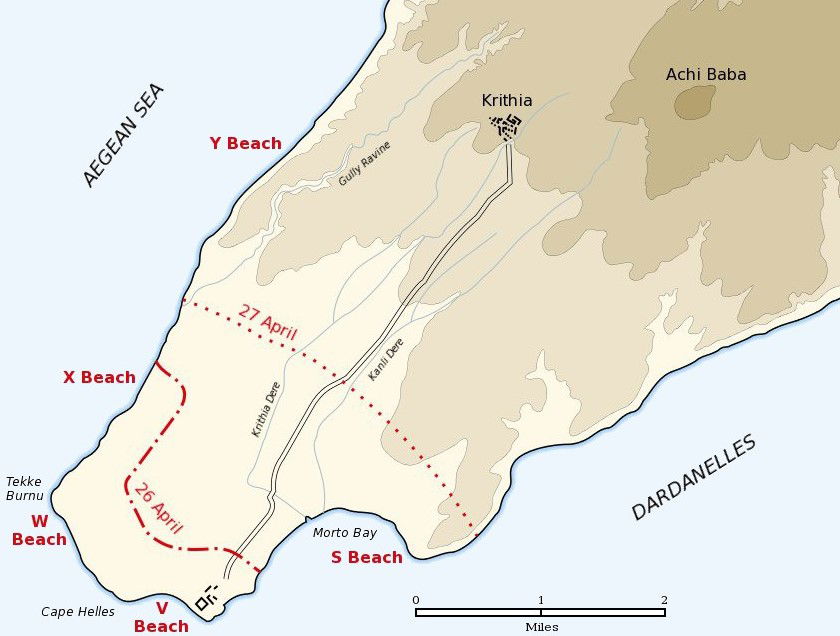

The locations of the five landing beaches at Cape Helles, Gallipoli

The locations of the five landing beaches at Cape Helles, Gallipoli

The Derfflinger arrived off the Dardanelles at 0530 hours on 6 May, disembarkation commenced on 'V' and 'W' Beaches at 1645 hrs and was completed at 2315 hrs. The General Officer Commanding, Sir Ian Hamilton had the beaches renamed 'Lancashire Landing' after the heroic efforts of the Lancashire Fusiliers who won six Victoria Crosses in the initial landings.

The Manchester’s spent the first night bivouacking on the bitterly cold beach. The blankets, stores and equipment had been left on board until the following day.

Lancashire Landing, Cape Helles, Gallipoli

Lancashire Landing, Cape Helles, Gallipoli

At 1900 hours on 7 May the Manchester's moved to the west of Krithia Bridge into reserve dug outs, before occupying reserve trenches the following day. On the 11th they moved up in to the support trenches, the next day the brigade made a feint attack to distract attention from movement elsewhere. On 16 May they occupied the front line trenches for the very first time.

The division was involved in three notable attempts to break out of the Helles bridgehead to capture the dominating heights around the village of Krithia. For the first attack, which took place between 6th and 8th May, only the Lancashire Fusiliers Brigade from the Division took part.

The troops soon learnt to take the threat from Turkish snipers seriously. They shot many men, officers and leaders being the prize target. Lieutenant Colonel Darlington wore webbing equipment, removed his badges of rank, and Sam Browne belt and pistol holster, replacing the latter with a rifle in an attempt to make himself a less conspicuous target for snipers. He wrote in his diary on 14th May 1915.

'The weather is perfect again. We had one day's rain and our trenches were a quagmire. We are still in the firing line reserve trenches and have to be careful showing up. Their snipers are very good and they now shell the trenches. They hit my dugout three times with shrapnel the night before last and my last dugout twice'.

'Young Walker was hit slightly in the head. Cyril Ainscough got a spent bullet in his foot and Cunningham was hit slightly in the face. They are all nothing and only Cunningham went to hospital. He was up here to see us to-day'.

'We have still no kits and I want a bath badly. I have a ground sheet and one blanket and no change, but it is much nicer having no luggage to bother about. The men take it very well, but of course have not faced much yet'.

'We had rather a bad time coming up, but it was more frightening than dangerous'.

'We have had one man killed and 20 wounded. The Turk aeroplane guns are beastly. The pieces fall and you can hear them coming for age, also sometimes you can see them falling in the sunlight, very slowly like a penny through water'.

'The Turks have a big gun up. They killed Frank James' horse with it yesterday. I am perfectly filthy with mud and want of a bath and change, but I am shaving. Archie Brook looks like a Turk himself with his beard'.

'I have stripped my badges, wear putties and a web kit and carry a short rifle'.

Here comes Archie. He wants leave to go out and bury 20 dead Turks just in front of his Trench. He is now with the Machine Guns. The aero is right over me now, I hope they won't shell it. It is a very good life this and makes you feel so fit.

5.15 p.m. I have been up and down the trenches all day driving people to deepen and improve. One gets sniped all the way. The country is a mass of furze and the snipers lie out in it for weeks with tinned food and snipe all day.

“They are apparently behind the lines and in between and are almost impossible to spot, the scrub is so thick.”

Third Battle of Krithia

On 25 May, the same day that the formation was re-designated as 127th Brigade, 42nd Division, the brigade moved up from the reserve trenches into the firing line. On 4 June the Manchester's finally received their baptism of fire when they took part in the Third Battle of Krithia.

The day started with a preliminary bombardment at 0800 hours, followed by a heavy bombardment three hours later. At 1120 hours there was a feint attack in an effort to divert the attention of the Turks away from the Manchester's. For the main attack 5th Battalion were in the centre with 8th Battalion to their left, 7th Battalion on the right and 6th Battalion in reserve.

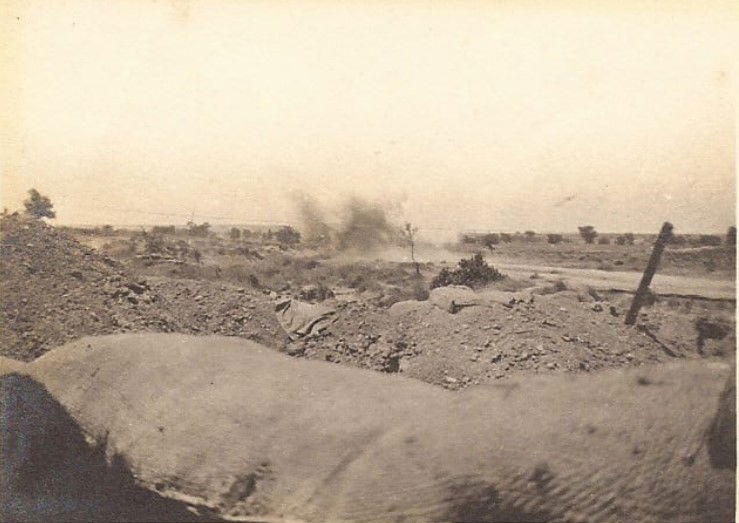

Shell landing on the Krithia Road

Shell landing on the Krithia Road

‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies from the 5th were the advance companies and captured the first line of trenches, where fierce hand to hand fighting took place. ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies then leapfrogged them and by 1215 hours had secured the second line of enemy trenches 500 yards further on, and only 500 yards from the village of Krithia.

The Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Ian Hamilton, observing the attack on HMS Wolverine wrote in his diary:

' ..... the boldest and most brilliant exploit of the lot was the charge by the Manchester Brigade in the centre, who wrestled two lines of trenches from the Turks; and then carrying right on; on to the lower slopes of Achi Baba, having nothing between them and it's summit but the clear untrenched hillside. Then lay there - the line of our brave lads, plainly visible on a pair of good glasses - there they actually lay.'

The withdrawal of French troops and the Royal Naval Division forced the 7th Manchester’s on their right flank to pull back leaving ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies of the 5th Battalion isolated and in a dangerous position in a salient ahead of all other allied troops. The Turks started to work round their right flank in an effort to cut the Manchester's off.

The two companies held on for six hours but with no reinforcements or support and in danger of being cut off they were ordered to withdraw back to the first objective, held by 'C' and 'D' Companies. On the first day of the battle Frank was given a battlefield promotion from Corporal to Sergeant after the battalion had suffered thirty eight killed in action and 137 wounded. The trenches were held during the first night despite two Turkish counter attacks.

The Manchester's still continued to hold the first objective during the next day despite receiving heavy enfilade fire and suffering casualties from the Turks who had entered their trenches on both flanks. They were unable to clear the enemy out due to a lack of bombs (Mills grenades), giving the four companies no choice but to withdraw back to their own front line trenches.

Despite artillery support which fired 1,700 rounds, shell fire from battleships and close support from four Rolls Royce armoured cars belonging to the Royal Naval Air Service the attack had been a failure.

A Turkish counter attack in the early hours of 6 June was repulsed, and for the next two days they remained in the front line trenches. The war diary entry for 7 June reported that the men were frightfully tired and suffering from want of sleep, but that morale was excellent. That day an attack by the 9th Manchester's on the left flank was successful, but owing to an unsuccessful assault by the Royal Marine Light Infantry they had to retire suffering heavy casualties in the process.

Finally at 1630 hours on 8 June they were relieved by the 9th Manchester's, the survivors of the battle moved back into Corps Reserve trenches. However no area of the Peninsula was safe from Turkish fire so troops who had just come out of the line were sent to the Greek islands for rest and reorganisation .

On 10 June the battalion received orders to stand by for embarkation to Imbros for reorganisation, but poor weather delayed their departure. Finally at 2000 hrs on 13 June the battalion left the reserve trenches. At 0300 hours the next morning they embarked aboard trawlers which transferred them to HMS Carron for the ninety minute journey to the island of Imbros.

Because of high winds and rough seas the disembarkation was delayed by six hours. The exhausted men finally pitched camp at 1530 hours. They spent a week on Imbros resting before returning to the peninsula.

The casualties over the four day battle were 56 killed in action and 178 wounded. These included the 127th Brigade Commander, Brigadier Noel Lee who was killed, and his replacement Lieutenant Colonel Heys who died shortly after.

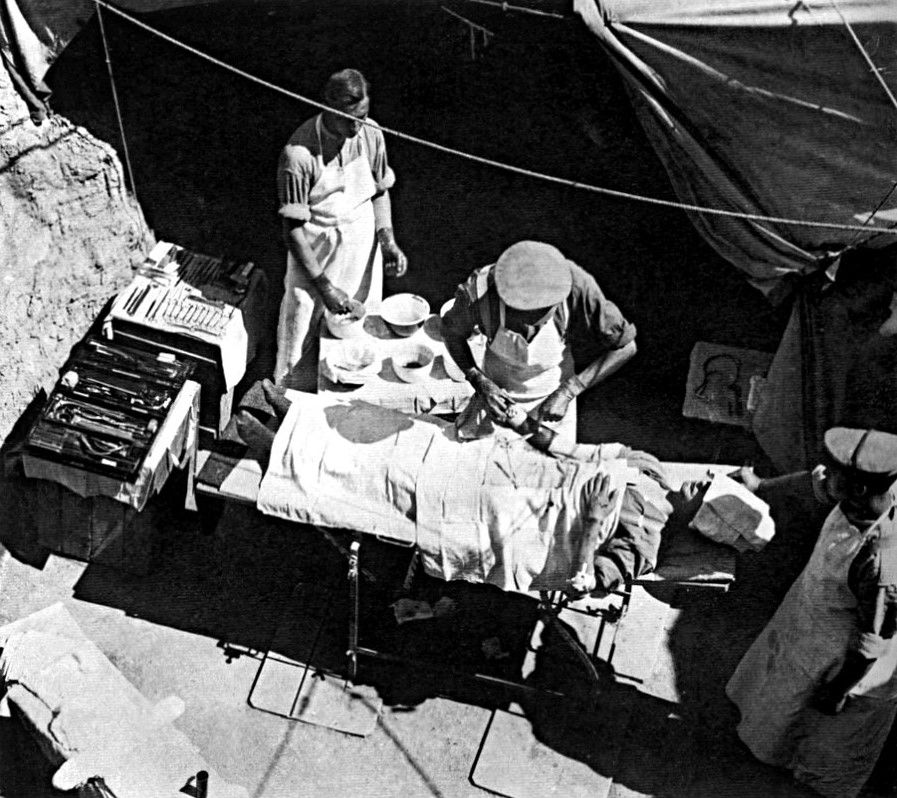

A surgeon from 2/2nd East Lancashire Field Ambulance of the 42nd Division removes a bullet from a wounded soldier in a makeshift Field Hospital at Cape Helles, Gallipoli.

A surgeon from 2/2nd East Lancashire Field Ambulance of the 42nd Division removes a bullet from a wounded soldier in a makeshift Field Hospital at Cape Helles, Gallipoli.

After the battle Lieutenant Colonel Darlington recommended four officers and two other ranks for awards for gallantry. These were Captain Woods and Lieutenant G. S James from 'D' Company, Second Lieutenant M. K Burrows, Captain Reddick of the Royal Engineers, Sergeant Whittle of 'D' Company and Lance Corporal Catterall.

Lieutenant George Sydney James who had been killed in action on the first day of the battle did not receive an award. He was buried in Redoubt Cemetery at Helles, Plot XE, Grave 20. He was 22 years of age. His older brother Captain Francis Arthur James was also serving with the 5th Manchester's. He was seriously wounded by a Turkish grenade on 16 September and died of his wounds two days later, aged 29.

The pair had two other brothers serving with 13th Battalion Middlesex Regiment in France. Charles who was killed in action ten days after Francis on 28 September, and Henry who died the following year on 18 August 1916.

Their father Charles was Vicar of St. David CE church in Haigh near Wigan, tragically he and his wife Emily had to suffer the loss of all their four sons within fourteen months.

Home to England

Great Uncle George was wounded on two separate occasions at Gallipoli. He first suffered a facial wound from shrapnel, losing all his teeth and was evacuated to Alexandria. On his return from Egypt he injured his leg on barbed wire carrying ammo up to the firing line. The wound became seriously infected and he was eventually evacuated back to the England on a hospital ship.

On his return George was admitted to a hospital in Manchester, then transferred to Wigan to recuperate at Woodlands No 1 Auxiliary Hospital in Wigan Lane run by the British Red Cross. The building was loaned by Lord and Lady Crawford of Haigh Hall in October 1914 and was the first Red Cross Hospital in the region to receive wounded soldiers. Lord Crawford himself served in the Royal Army Medical Corps on the Western Front as a medical orderly. Whilst home in Wigan George got to meet his son Frederick for the first time, who had been born in February 1915 while he was in Egypt.

On 9 August 1916, following his recovery, he transferred from the Manchester Regiment to the Royal Flying Corps, putting his carpentry skills to good use as an aircraft rigger. (The Royal Flying Corps was eventually merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to create the Royal Air Force).

Airman George Taylor Royal Flying Corps

Airman George Taylor Royal Flying Corps

Battle of Krithia Vineyard

The Battle of Krithia Vineyard was planned to divert attention away from the landing at Suvla Bay and the break out from Anzac Cove, and would consist of two separate attacks over two days, the 6th and 7th of August, with a follow up action dependent on the success of these initial assaults.

The width of no-man's-land was shortened by a series of night digs that sapped the line forward. This brought the jumping off point for the attack to within 250 yards of the Turks. Two brigades from 42nd Division and a brigade from 29th Division took part in the operation but faced overwhelming Ottoman Forces consisting of four divisions with two more in reserve.

The 5th Manchester's took part in the first day's action and were attached to 88th Brigade from the 29th Division. The three battalions from 88th Brigade were 1st Battalion Essex Regiment, 2nd Battalion Hampshire Regiment and 4th Battalion Worcester Regiment. Their mission was the capture of 'H' Trench.

The 5th Manchester's were on the Worcester's right, their task was to attack two Turkish trenches, which were being used as bomb stations, 'A' and 'D' Companies were to attack trench H 11a with 'B' and 'C' Companies to assault trench H 11b, both of which overlooked the deep ravine of Krithia Nullah. Neutralising these bomb stations was important as they would pose a threat to 42nd Division's attack the following day. The preliminary bombardment to the attack started at 1400 hours but failed entirely to neutralise the enemy trench line.

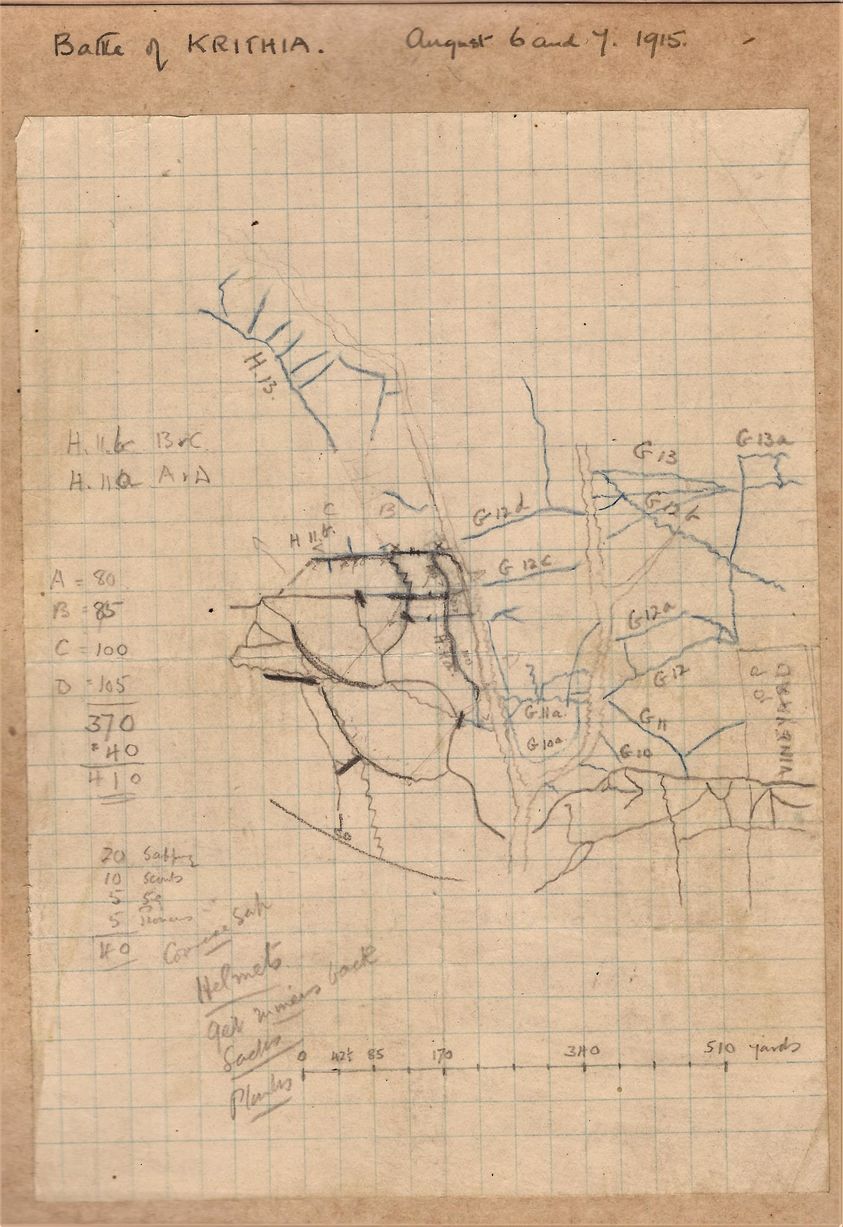

A sketch by Lieutenant Colonel Darlington showing the battalion's objectives at Krithia Vineyard on 6 June 1915.

A sketch by Lieutenant Colonel Darlington showing the battalion's objectives at Krithia Vineyard on 6 June 1915.

On leaving their trenches at 1540 hours all the battalions came under murderous rifle and machine gun fire and shrapnel from artillery shells. The Essex captured their part of 'H' Trench but were later pushed out by counter attack. The Hampshire's were cut down by machine guns before they even reached their objective.

The Worcester's managed to reach the enemy trenches, a group of thirty men led by a Sergeant managed to occupy a section of 'H 13' trench thirty or forty yards in length. They remained there all day against overwhelming odds; just twelve survivors returned to their original line after midnight.

The 5th Manchester's on the right flank also took heavy casualties during the assault. They got in amongst trenches H11a and H11b but failed to hold them. The battalion war diary notes that 'our own artillery dropped some shells in our own trench. No counter attack'.

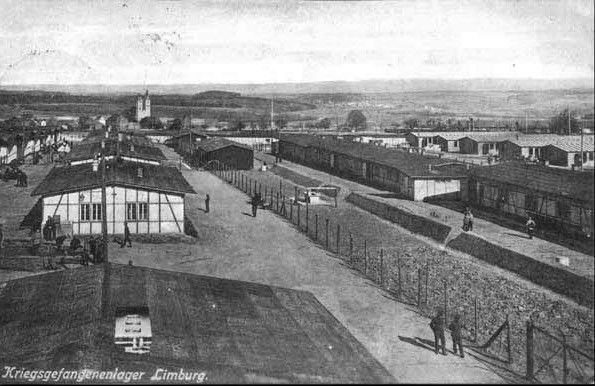

The attack had been a complete failure, largely in part to the failure of artillery support. The Worcester's came off worse, losing sixteen officers and 752 other ranks in the attack, at least three officers and sixty-eight other ranks, mostly from 'X' Company were captured and spent the remainder of the war in a Turkish Prisoner of War Camp. This was the worst single day's casualties of any battalion at Gallipoli.

It's 768 casualties in one day amounted to 93 percent casualties, killed, wounded or missing. These were shocking statistics in the context that it was supposed to be merely a diversionary attack in support of the Anzac and Suvla operations.

At 0900 hours the next morning the preparatory artillery bombardment for the second phase of the operation started, with the attack going in at 0940 hours. 42nd Division less 5th battalion were ordered to attack H 11a and H 11b trenches again. The infantry attack failed and the battalion war diary was once again critical of the artillery. Noting that the preliminary bombardment was ineffective and they had been badly shelled by their own artillery causing at least thirty casualties. That night they received 100 reinforcements from the 9th Manchester's.

Over the two day period of the battle, 5th Battalion suffered twenty killed in action, 158 wounded and 51 missing, a total of 229 casualties.

Frank was wounded on 6 August, receiving a bullet wound to his back. He was evacuated to 19th General Hospital in Alexandria for treatment, followed by a spell in the nearby Mustapha Convalescent Camp which had been set up by Lady Haig, the wife of Field Marshall Haig.

No. 19 General Hospital, Alexandria, Egypt

No. 19 General Hospital, Alexandria, Egypt

Sergeant Thomas McCarty won the Distinguished Medal for bravery that day for rescuing some of his men trapped in a trench. An account from the Wigan Military Chronicle held at the Imperial War Museum tells the story.

'Sgt. T. McCarty twice rushed the enemy bomb pit under heavy rifle fire and although men from neighbouring platoons found their way into the position, they were all casualties. After about an hour, as there were not enough men to offer an effective resistance, Sgt. McCarty, again working under a hot and accurate rifle fire, tore away a sandbagged barricade and extracted the whole of the party including all of the wounded. A survivor wrote shortly afterwards, "All the time he was working they were shooting at us down the trenches, every shot hit, and if he had not made the road none of us would have got out'.

Sgt. Major Thomas McCarty DCM

Sgt. Major Thomas McCarty DCM

(Thomas who later became a Sergeant Major was a well-known Wigan wrestler. In 1919 he was appointed trainer for Wigan Rugby League Club, a position he held for twenty years. He was trainer when Wigan won the Challenge Cup for the first time in the 1923-24 season beating Oldham 21-4. Also when the final was played at the Empire Stadium, Wembley for the first time in the 1928-29 season when Wigan beat Dewsbury 13-2. Thomas died in 1954 aged 71, at the time he was living in Orchard Street, Scholes. He is buried in Gidlow Cemetery, plot 19, grave 469 RC.)

Killed in action on 6 August was Captain Cyril Ainscough, the Officer Commanding 'A' Company. Despite being ordered by Lieutenant Colonel Darlington not to go in the first wave, he never the less led his men in charging the enemy positions. He had already been wounded three times at Gallipoli and had recently returned from hospital in Alexandria. Twenty two years old Cyril was from a prominent local family and lived at Fairhurst Hall in Parbold. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Cape Helles Memorial, stone number 158A. There is also a stone tablet to his memory in Our Lady & All Saints RC church in Lancaster Lane, Parbold.

Captain Cyril Ainscough, killed in action 6 August 1915 at the Battle of Krithia Vineyard, Gallipoli.

Captain Cyril Ainscough, killed in action 6 August 1915 at the Battle of Krithia Vineyard, Gallipoli.

Trench Warfare

From September onward there were few offensive operations and Helles settled down to trench warfare. The troops were employed sniping, bombing, carrying parties up to the front line, trench improvements, and salvage duties day and night.

5th Manchester's in reserve trenches

5th Manchester's in reserve trenches

After three months recuperating in Egypt Frank had recovered enough to re-join his battalion in the Dardanelles, his pay book shows that he was paid in Mudros, Greece in November and that he received £2 pay at Gallipoli on 13 December. Four days later he was promoted to Acting Company Quartermaster Sergeant (CQMS).

His role as CQMS of ‘B’ Company made him the second most senior Non Commissioned Officer in the company and deputy to the Company Sergeant Major. His day to day job entailed being in charge of the company’s general stores, including the horses and wagons, and for the issue of weapons, ammunition, equipment, clothing, rations and provisions.

Inhospitable Conditions

Gallipoli had been an inhospitable place to fight a war, characterised by rocky ground with little vegetation and hilly land with steep ravines. During the summer months, it was blisteringly hot and 100 degrees in the shade was registered.

The heat, putrefying bodies left in no-man's-land and unsanitary conditions led to huge swarms of flies and mosquitos which made life almost unbearable for the men there. The flies plagued them all the time, covering any food they opened, which helped the spread of disease such as jaundice and dysentery.

Bivouac in Gully Ravine

Bivouac in Gully Ravine

By the end of July all members of the battalion had been given the Cholera inoculation but the war diary entry for 18 August states that Veldt Sores (the symptoms of infectious cutaneous Diphtheria) was now prevalent.

Despite several truces arranged to recover and bury the dead there was a constant smell of a mix of human excrement (diarrhoea was a major problem and troops could not leave their trenches for proper field latrines) and that from bodies decomposing in the heat.

The extreme weather conditions on the peninsula meant that the temperatures could also plummet, and in the autumn and winter of 1915, large numbers of troops suffered from trench foot and frostbite. In November the weather deteriorated rapidly with heavy rain and snow flooding trenches and dugouts, the former becoming canals forcing men to stand precariously on the narrow fire-steps and risking becoming targets for snipers.

There were reports of British soldiers dying of exposure or drowning in the torrential downpours and flooded areas. Over 5,000 more had to be evacuated, suffering from frostbite and hypothermia. One particularly violent storm, with hurricane force winds, rain, sleet and snow, swept the Peninsula from the 26th to 28th November, destroying the piers and lighters on the beaches upon which the Force was entirely dependent for its supplies.

Every drop of water on the Allied side had to be brought to the peninsula by sea. Consequently it was mostly used for cooking. There was never enough for drinking especially in the heat of the summer. Even less was available for personal hygiene which made the troops more susceptible to sickness, disease and the ever present lice.

The rations supplied to the troops consisted mainly of tinned salted bully beef, Maconochies stew, bacon, cheese, hard tack biscuits, and apricot jam, the sparse amounts available was a source of much complaint. Many men became malnourished and suffered from ulcers.

The Evacuation

In October 1915 the overall commander at Gallipoli General Sir Ian Hamilton was recalled to London, effectively ending his military career. His replacement, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Munro arrived on 28 October to take charge. Two days later he had visited all three sectors of the front line and quickly concluded that the campaign had been a failure and that there was no realistic chance of capturing the peninsula. He recommended that a phased withdrawal from Gallipoli be undertaken.

Winston Churchill on learning of the suggestion criticised Munro saying: He came, he saw, he capitulated'.

Lord Kitchener decided to see Gallipoli for himself and sailed for Gallipoli in early November. He was shocked by what he saw. On 15 November he cabled the Dardanelles Committee that he had reached the same decision as Munro.

Churchill, the architect of the ill-fated campaign was on the receiving end of much criticism, forced out of office and demoted. He resigned from the government and elected to become an infantry officer on the Western Front. He became Commanding Officer of the 6th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers in France until April 1916, after which he returned to government.

On 7 December the Committee finally decided to evacuate the peninsula. Because of the obvious dangers of a fighting withdrawal it was decided to devise a deception plan. The Allies needed to evacuate around a quarter of a million men. Firstly the French troops were taken off to simplify the command structure.

Because of a lack of available shipping a two stage evacuation plan was devised, Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay would be first, followed by the Helles bridgehead. The main architect of the Anzac and Suvla evacuation plan was Lieutenant Colonel Cyril Brudenell White, the ANZAC Chief of Staff.

The Anzac evacuation was to be in three stages, the first two were kept on a 'need to know basis'. Troops were told they were going to Lemnos for a rest.

Firstly all non-essential troops were evacuated along with the horses and mules, artillery pieces, vehicles and equipment. Anything that was to be left behind was either dumped in the sea, destroyed or buried.

To lull the Turks into a false sense of security rifle and artillery fire was reduced to minimum to get them used to quiet spells. In an appearance of normality cricket and football matches were played in the rear areas that were overlooked by the Turks.

At night, from the positions north of Walker's Ridge stretching through the ranges to Hill 60, mule columns looked after by men of the Indian Mule Corps took supplies up to the front line troops as normal. Unbeknown to the Turks they returned to William's Pier on North Beach heavily laden with material for evacuation.

To maintain the appearance of normal operations though, some material was still brought ashore at the Anzac Cove and North Beach piers during the day. On the beaches the illusion of stacks of wooden ration crates was created by means of constructing an outer framework only, making it appear the massive piles were solid.

During the next phase the number of fighting units were gradually thinned out leaving enough on the front line to withstand a Turkish attack. So as not to be picked up by aerial observation their presence in the trenches was supplemented by uniformed, scarecrow like dummies made out of straw filled old jackets and hats.

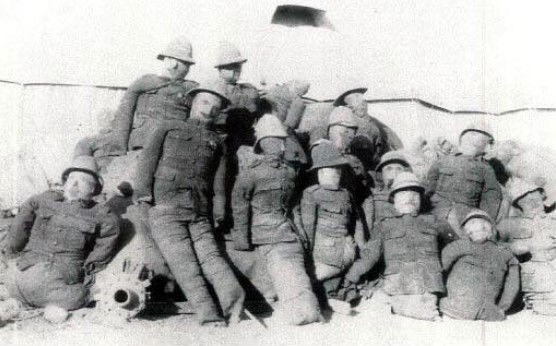

Straw dummies used as part of the deception plan in the evacuation of Gallipoli

Straw dummies used as part of the deception plan in the evacuation of Gallipoli

When the troops realised that they were being evacuated many paid visits to the little graveyards scattered all around to tidy them up and pay their last respects to fallen comrades.

An ingenious invention by Lance Corporal William Scurry of 7th Battalion, Australian Infantry Force was the 'drip' rifle, a self-firing rifle. This was to play an important part in the success of the operation.

Firstly a rifle was wedged into position on the parapets of the front line trenches. An empty ration can or kerosene tin was hung from the trigger by a string, another tin higher up with a hole in the bottom was filled with water. The water in the top tin dripped into the bottom one, eventually the weight pulled the trigger firing a round off. The holes in the top tins were of different sizes, ensuring that rifles would fire at intermittent intervals, from twenty minutes to an hour.

The drip rifle invented by Australian William Scurry

The drip rifle invented by Australian William Scurry

By 19 December only 10,000 soldiers were left to be evacuated, and on that day the British at Helles launched feint attacks in an effort to divert attention away from Anzac.

On the last night little presents were left in the trenches for the Turks to find in the form of booby trapped watches, hats, boots and personal equipment. At 0230 hours on the morning of the 20th the last remaining 300 troops of the rear parties set their drip rifles which would keep firing long after they had departed.

With hessian sacks wrapped round their boots they crept away for the 35 minute walk to the beach and on to HMS Cornwallis, the last ship to leave Anzac North Beach. The plan worked perfectly with no incidents or casualties.

The same plan and tactics that had been employed at Anzac and Suvla so successfully were used at Helles. At 2130 hours on 29 December 1915 it was the turn of the 5th Manchester's, the remnants of the battalion embarked at ‘V’ Beach onto SS Hibernia and then transported to Mudros on the Greek Island of Lemnos.

By 9 January 1916 the last of the Allied troops had been taken off the peninsula with hardly any casualties. Although the campaign on the peninsula had been a disastrous failure, the overall evacuation was a brilliant success.

The Cost

It is no understatement to say that Gallipoli was one of the worst fronts to serve on in World War One. During the eight month campaign 559,000 allied troops took part, 420,000 from Britain and the Empire, 80,000 French, 50,000 Australian, 9,000 from New Zealand and 1,000 Newfoundlander's. (Newfoundland was a British Dominion and wasn't to unite with Canada until 1949).

In 1913 the Germans established a military mission in Constantinople led by General Otto Liman von Sanders and by the outbreak of World War One all land, sea and air forces, were commanded by German officers, as was weapons and ammunition production.

It is estimated that between 1,600 to 1,700 German military personnel were directly involved in the fighting at Gallipoli. These included 400 navy gunners manning the coastal artillery, 150 field artillery gunners, 300 marines made up machine gun teams using the infamous Maxim machine gun, 250 pilots and technicians from the navy and air force, 400 pioneers, and a field hospital containing 50 doctors and nurses. Also there was 100 command, communications, and logistics personnel.

The allies suffered over a quarter of a million casualties, 58,000 killed in action and 196,000 wounded or sick. Disease and sickness produced considerably more casualties than the fighting itself. The Ottomans, including some Germans suffered a third of a million casualties, including 87,000 dead.

The 5th Manchester's had suffered a total of 686 casualties, comprising of 151 dead, 478 wounded and 57 missing. Men also died of sickness and disease. Six separate drafts had arrived, bringing in 361 replacement troops for the battle casualties.

On withdrawal the effective strength of the battalion was 239 all ranks from a total of 1,179 who had fought in the campaign. From the original 818 members of the battalion that started the campaign only 152 remained and from the 361 replacements, only 87. A costly attrition rate of eighty per cent casualties. 42nd Division's casualties at Gallipoli were 395 officers and 8152 other ranks killed, wounded or missing.

Helles Memorial, Gallipoli

Helles Memorial, Gallipoli

The Helles Memorial to the Missing stands at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula and contains 20,960 names. It takes the form of an obelisk 30 metres high and can be seen by ships passing through the Dardanelles Straits. There are four more memorials to the missing on the peninsula and thirty one Commonwealth War Graves cemeteries,

The Sinai Campaign

On 18 January 1916, after sitting out a violent storm for five days, 5th Battalion left their tented Camp at Sarpi and returned to Egypt. After disembarking in Alexandria they travelled by train to Cairo and then by road to another tented camp at Mena adjacent to the Great Pyramids of Giza. On 10 March 1916 42nd Division became part of the newly formed Egyptian Defence Force for the upcoming Sinai and Palestine Campaigns.

Although the Turkish Army had suffered heavy losses in the Gallipoli campaign the threat to the security of the Suez Canal from the Ottoman Empire still remained. The importance of the canal to the British Empire cannot be underestimated and it was vital that it was kept open as a gateway through the Red Sea to India and the Far East.

The Canal Zone stretched 120 miles from Port Said on the Mediterranean coast to the Gulf of Suez. There are three routes by which a hostile force might approach the canal. The northern Caravan route along the coast through El Arish to Kantara, the route by which Joseph’s brethren, and later the Holy Family, and in more recent times Napoleon and his army in 1798 had travelled from Palestine to Egypt. The central Hassana to Ismalia route and the southern Akaba to Suez route. It was Akaba that Lawrence of Arabia was to attack and capture the following year with a force of Arab tribesmen.

Up to present the Canal defences had been on the West Bank, close to the canal. It was now recognised that it had to be defended from the eastern side, so it was decided that a line of outposts was to be constructed in the desert, far enough out to prevent the enemy from bringing guns into action within seven miles of the waterway. These posts were to be garrisoned by a battalion of Infantry, a battery of Royal Artillery, a troop of Yeomanry Cavalry and a section of Royal Engineers.

After a couple of weeks in Cairo resting, refitting and absorbing much needed reinforcements into the various battalions, 42nd Division was assigned to cover the southern Akaba to Suez route. They moved to Jabal ash Shallufa, at the southern end of the Great Bitter Lake and twelve miles or so north of Suez, concentrating in a camp in the desert east of the Suez Canal.

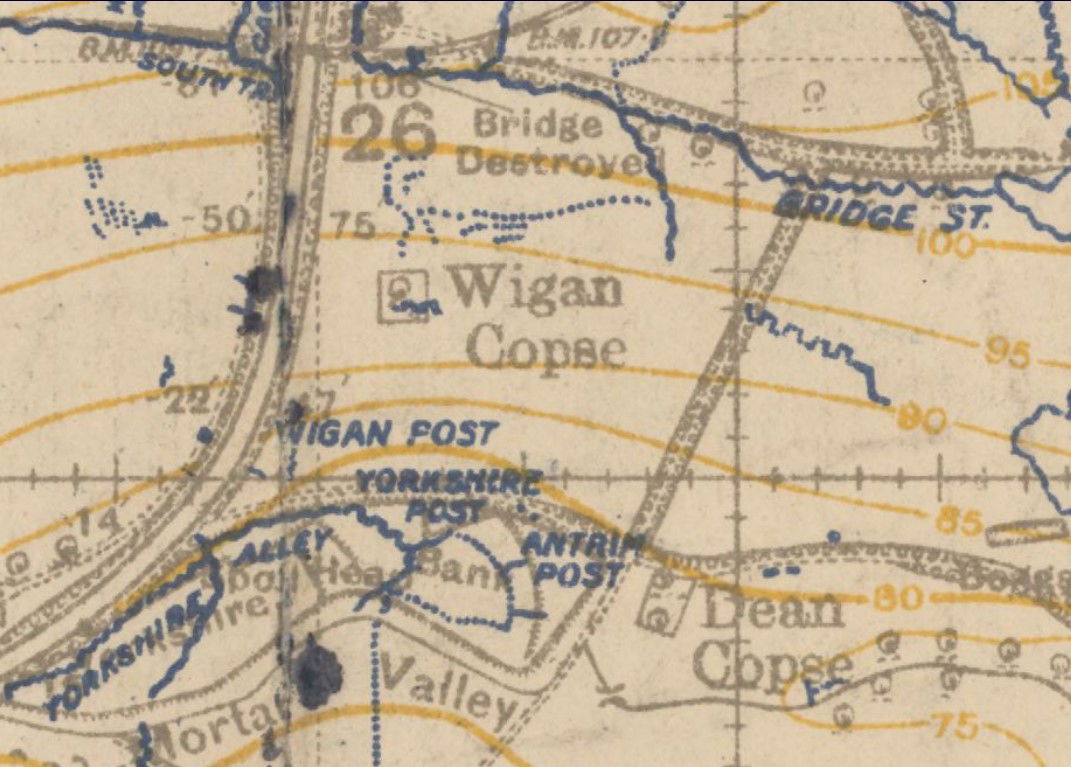

Miles of barbed wire entanglements were put up and trenches were dug and revetted with wooden frames and hurdles backed with canvas in an effort to stop the sand from refilling the trenches. In due course roads and light railways were run out to the posts, and three inch water pipes were laid. Each post was named after the depot towns of the battalions, Manchester, Salford, Ashton, Wigan etc.

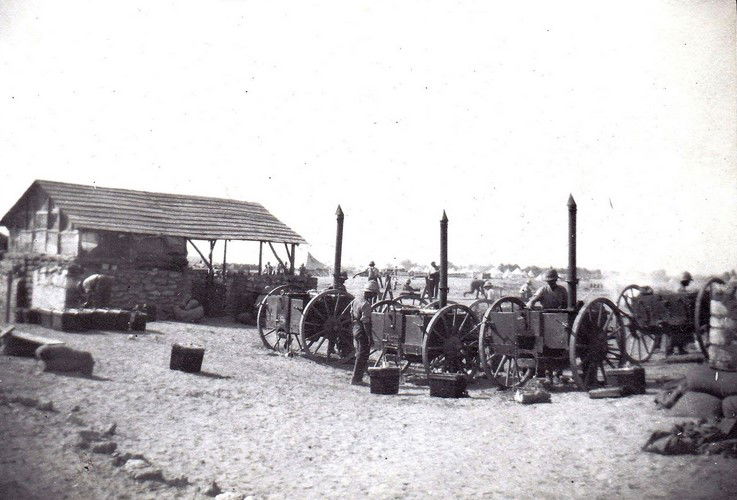

Field kitchens at Suez 1916

Field kitchens at Suez 1916

At the beginning of April, after a two month stint manning the outposts, the division left Shallufa to camp in the desert about two miles north west of Suez. Engineers erected a large number of huts and a macadam road was made through the camp. In this more permanent camp conventional military and physical training was undertaken in earnest, relieved by games and sports such as rugby, football, wrestling and hockey. Donkey polo and camel racing brought a welcome distraction and entertainment for the troops.

As was to be expected the rugby team from the 5th Manchester’s based around the Wigan area won great acclaim and beat all comers. As did the famous wrestlers from the battalion such as Thomas McCarty. Canteens were set up to provide the troops with cigarettes, biscuits, chocolate and other sundries. A Dramatic Society was formed and plays put on at the ‘Theatre Royal’.

The Battle of Romani

On 19 June, 42nd Division was ordered to relieve 11th Division in the El Ferdan sector in the central section of the Canal Zone, midway between Ismalia and Kantara, the 5th and 7th Manchester’s were attached to the 52nd Lowland Division further to the north. The heat was unbearable with temperatures of 120 degrees in the shade normal, and temperatures of 105 degrees at midnight registered on two occasions.

Troops falling in and collecting weapons

Troops falling in and collecting weapons

Towards the end of July information was received that the 18,000 strong Ottoman 4th Army led by German General Frederich Kress Von Kressenstein, was moving swiftly westwards along the Mediterranean coastal route towards El Arish. 42nd Division was hurriedly ordered north to Kantara, the 6th Manchester’s based at Pelusium heard artillery fire from the direction of Romani announcing that the Turkish attack had begun. The remainder of 127th Brigade was ordered to Pelusium and just as the last battalion was detraining Brigadier General Ormsby received the order to march at once in support of the Anzacs who were heavily engaged in the area of Mount Royston, to the south of Romani.

Within three minutes of receiving the order the 5th, 7th and 8th Manchester’s moved off into the desert leaving 6th Battalion to await the arrival of the supplies and transport. As the Brigade neared the Anzac positions with the 5th and 7th battalions leading they could see the Turkish shrapnel bursting overhead. At about 2,000 yards from the enemy positions the two leading battalions extended into lines, the 7th on the left, the 5th on the right and attacked the ridge of Mount Royston.

With the arrival of 127th Brigade the enemy fell back, some surrendering. The Anzacs then went on the attack from defence, their cavalry sweeping behind the hill to cut off the fleeing Turks. Seven officers and 335 enemy soldiers were captured.

127th Brigade had marched across three miles of deep loose sand, suffering under a blazing sun, in the hottest season of the year and came into action less than 1 hour 33 minutes after receiving orders to move.

The action prompted a congratulatory telegram from King George V himself which read: ‘Please convey to all ranks engaged in the Battle of Romani my appreciation of the efforts which have been brought about the brilliant success they have won at the height of the hot season and in desert country’.

The Battle of Romani was the first large-scale mounted and infantry victory by the British Empire in the First World War. It occurred at a time when the Allied nations had experienced nothing but defeat, in France, at Salonika and in Mesopotamia. British casualties in the battle were 70 killed in action, 27 later dying of their wounds and 259 wounded, a total of 365.

Following the victory at Romani, which had effectively ended the immediate threat to the Suez Canal, Commonwealth Forces pursued the Turks through the desert, defeating them two days later at Katia. This series of successful British infantry and mounted operations resulted in the complete defeat of the Ottoman force, which suffered an estimated 9,000 casualties and nearly 4,000 taken prisoner.

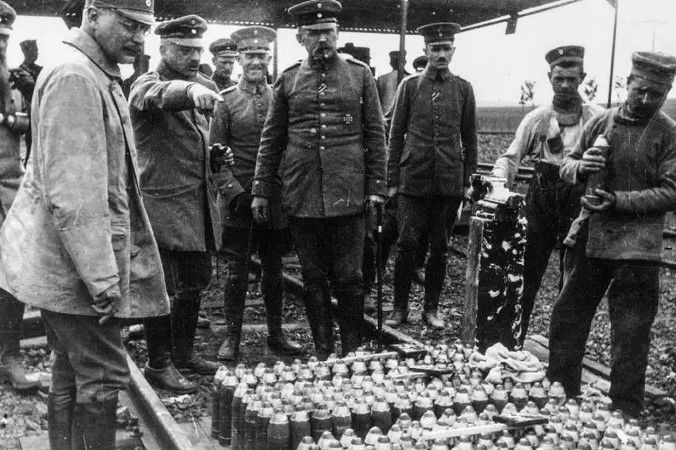

Also captured were a mountain gun battery of four heavy guns, nine machine guns, a complete camel-pack machine gun Company, 2,300 rifles, a million rounds of ammunition, and two fully equipped field hospitals. While a large quantity of stores in the supply depot at Bir el Abd was destroyed. All the captured arms and equipment were made in Germany, and the camel-pack machine gun company's equipment had been especially designed for desert warfare.

On 9 January 1917 a desert column of the Mounted Anzac Division, attacked and defeated an entrenched 2,000 strong Ottoman Army at El Magruntein to the south of Rafah, close to the frontier between Egypt and the Ottoman Empire to the north and east of Sheikh Zowaid. The Battle of Sinai was over.

In early February 1917 the soldiers of 42nd Division discovered they would not be remaining in Egypt to take part in the Palestinian campaign, which would culminate in the capture of the Holy City of Jerusalem. Instead they were scheduled to depart Egypt for France and join the war on the Western Front. Now their experience and reputation gained as a fighting force would be put to a greater test.

The 42nd Division had proved the doubters, including Lord Kitchener, wrong. The part time soldiers from Lancashire had built up an enviable reputation in Gallipoli and Egypt which won praise from all quarters. On 20 February 1917, before their departure the Commander in Chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, General A. J Murray wrote to Major General Sir William Douglas KCMG, CB, DSC, the Commander of 42nd Division.

'Dear Sir William Douglas

It is always a grief to a Commander to lose any of his troops and I am very grieved at having to part with the magnificent Division under your Command.

The 42nd Division is going where the greatest call is being made on the Empire and I have not the least doubt that it will add in France further credit to that it has already gained on the Canal and in Gallipoli in 1915, and in the Sinai Desert in 1916. It is a record to be proud of. The appearance of the Division on parade today, it’s steady marching, smartness and fit of equipment reflects the greatest credit on you, your Brigade Commanders and all ranks.

I wish you and the whole 42nd Division God speed in your new adventure and feel sure that one and all will do their duty to the utmost of their power and that after the arduous training of desert campaigning, hardships will have no terrors for the Division.

Goodbye and good luck to you all.'

The rising casualty rates of front line units meant an increasing number of soldiers transferring between regiments. The Territorial Force four digit regimental numbering system tended to cause confusion, so on 1 March 1917 a new system was introduced where each battalion was allocated a block of 6 digit numbers. The 5th Battalion was allocated numbers 200001 to 250000. Frank’s new number was to be 200036. From now on casualty replacements would come from various regiments and depots and from all parts of the country. The headquarters was still Wigan and at its core were local soldiers but it would cease to be an all Lancashire battalion.

The Western Front

At 0900 hours on 2 March 1917, Frank was among thirty one Officers and 919 other ranks of the 5th Manchester’s who left Egypt after two and half years active service in the Middle East. They departed Alexandria onboard the Troop Transport ship ‘Corsican’ and sailing via Malta they arrived at Marseilles on the 8th. The sea was too rough to enter harbour so disembarkation only commenced at 1400 hours the next day.

After their trials and tribulations on the Gallipoli Peninsula and the deserts of Egypt and Sinai the Territorials from Lancashire were about to experience trench warfare in France and Flanders for the first time. The Western Front stretched 440 miles from the Swiss Frontier to the North Sea in Belgium. For the next two years they were to lead a nomadic life, marching hundreds of miles up and down the front line, from Peronne in the Somme Valley to Nieuwpoort Bains on the Belgian coast.

From the docks at Marseilles they were transported 590 miles by train to Pont Remy, near Abbeville in Northern France, followed by an eleven miles march to billets in Cerisy-Buleux. 42nd Division were now part of 3rd Corps of the 4th Army under the command of General Henry Rawlinson.

The next two weeks were spent training and refitting, they handed in their obsolescent Long Magazine Lee Enfield rifles and were equipped with the modern Short Magazine versions. On 28 March the battalion left Cerisy-Buluex and started the slow inexorable journey east to the front line and whatever fate awaited them.

They travelled via Hallencourt, Pont Remy and Chuignolles to Villers Carbonnel, where from 31 March to 21 April the battalion was in Corps Reserve employed on road-making, with the exception of ‘B’ Company which was employed in the erection of the new Fourth Army Headquarters. From Villers Carbonnel the battalion moved via Peronne to Flaucourt where they underwent four more days training prior to going in the line.

The weather during this period was very poor with rain and even snow falling. After being in the Middle East for the last couple of years the battalion suffered badly from the weather conditions and during the month of April a total of 53 men were admitted to hospital. However the Commanding Officer reported that the battalion was still in good shape.

Whenever possible new divisions to the Western front were assigned to a quiet sector of the line in order to gain experience of life in the trenches. They would be used as defensive troops holding the line, until they were deemed capable enough to be used as offensive attacking troops.

On 30 April the battalion relieved their sister unit the 7th Manchester’s for their first spell in the trenches at Epehy, halfway between Cambrai and Saint-Quentin. ‘B’ Company occupied the left sub-sector, ‘D’ Company on the right, ‘C’ Company were in support, with ‘A’ Company in reserve. Epehy proved to be a quiet sector apart from the daily shelling.

That day the war diary noted that the strength of the battalion was 1008 all ranks, broken down as follows:

There were twenty seven officers & 787 other ranks with the battalion. Five officers and 55 other ranks were on courses of instruction. Eight officers and 106 other ranks were on leave. Two officers and 20 other ranks were sick and three officers and 40 other ranks were detached on other duties.

On 1 May 1917 the battalion suffered their first casualty in France, who was wounded from shellfire. The next day the Commander of 127th Brigade, Brigadier Ormsby was killed by artillery fire whilst touring the front line. Lt. Colonel Darlington took over temporary command of the brigade, the command of the 5th Manchester's being entrusted to Major E. Fletcher.

The next day the battalion handed the trenches over to the 7th Manchester’s and came out of the front line into reserve positions. Whilst in reserve two companies had to be ready to move up to the front line at 30 minutes notice.

The Brigade now fell into a routine, consisting of tours of duty in the front line trenches, a move back to the reserve trenches, followed by a short periods as Brigade Reserve, then rotating back into the front line.

Intermittently, when the tactical situation allowed it, the battalion would go into Divisional Reserve, or even Corps Reserve, moving to a safe rear area for rest and refitting. There would be a visit to the divisional showers, reissue of kit and equipment and integration of draft replacements from depots in France and England. There would be regular church parades and visits by senior officers awarding gallantry medals, training programmes would then start.

These included route marches, weapon training, musketry on the ranges and instruction in gas warfare, not forgetting the more mundane tasks of guard duties or fire piquet. As well there would be recreational activities and sports which relieved the stress of war and the monotony of soldiering. The army saw sports as good for morale, fitness, and keeping soldiers out of trouble.

In their spare time, soldiers gathered in the YMCA hut, the centre of their social life, and wrote letters and diaries, read books and magazines, pursued hobbies, played cards or gambled. The cycle would then continue with a move back into Brigade Reserve. This system of rotation, along with occasional leave to England, prevented many soldiers from breaking down.

Brigade Reserve invariably involved work details, such as moving ammo and stores up to the firing line or helping the Royal Engineers digging and repairing trenches, wiring and road making. Sometimes they acted as labourers for the tunnelling Companies.

The Trench System

It was widely acknowledged that German trenches and defensive positions with deep reinforced dugouts were far superior to that of the British. When hostilities stalled after the Battle of Marne in September 1914, the Germans withdrew to a fortified trench line. By the end of 1914, both sides had dug in for a long war of attrition.

In contrast to the British trenches, the German trenches were defensive structures, sophisticated and elaborate, with some of the living quarters almost 50 ft. below the surface. Some German trenches had electricity, beds, toilets, and other necessities that differed from the open-air trenches of the Allies.

However the British Army discouraged making trenches too fortress like as they were considered only temporary structures from which to dominate ‘No Man’s Land’, conduct offensive operations and gain ground.

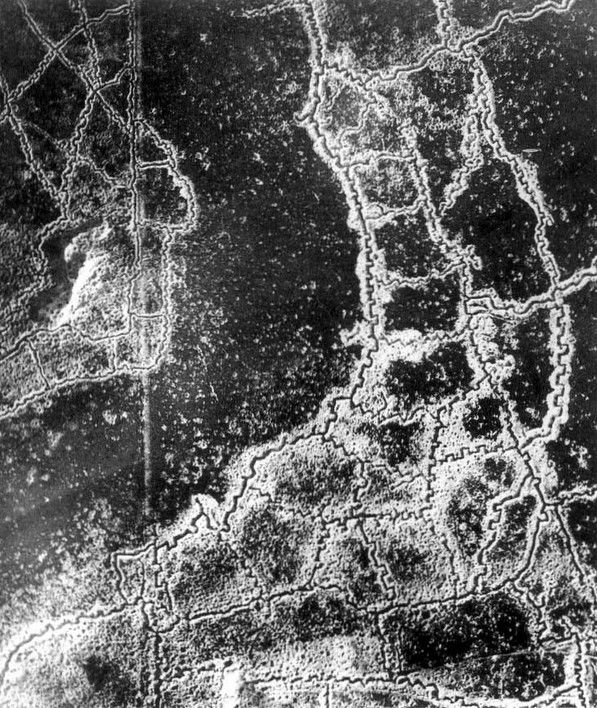

Aerial view of the trench network on the Western Front showing the area of No-Man's-Land in between the opposing trenches

Aerial view of the trench network on the Western Front showing the area of No-Man's-Land in between the opposing trenches

Trenches weren't dug in straight lines but in a zig zag or castellated pattern to prevent the enemy firing along the trenches and to limit the blast effect from artillery and mortar shells. Sometimes the trenches were just dug straight into the ground. This method was called entrenching. It was fast, but left the soldiers open to enemy fire while they were digging. Sometimes they would build the trenches by extending a trench on one end. This method was called sapping. It was safer, but took longer. The safest way to make trenches without enemy interference was tunnelling but it was the most difficult method. When the tunnel was complete the roof was removed.

The Allies used four types of trenches. The first was the front-line trench (firing trench) which would be at varying distances from the enemy front line depending on the terrain or tactical situation.

Behind the front line was the support trench which, as its name implies, supported the front line trenches with reinforcements and supplies.

After the support trench lay the reserve trench which was an emergency for the soldiers if they were ever overrun. Connecting these trenches were the communication trenches which allowed the soldiers to send messages, men and supplies between the trenches without going overground.

Life in the trenches

Life in the trenches

A typical trench was about six feet wide and eight or nine feet in depth with a rampart of soil on the lip. Along the lip was a line of wire connected to pickets called an apron. Further out were lines of thick barbed wire entanglements or concertina wire. A tactic used was to set up barbed-wire entanglements in a way that channelled attacking infantry into the killing zones of machine gun fire.

Being a member of a wiring party was a very common task for every infantryman. This work, carried out at night, involved carrying out steel pickets six feet in length and rolls of wire. The pickets were knocked into place by mallets muffled with sandbags. Later a spiral shaped picket was used that could be screwed into the ground without making a noise.

Because flooding was a problem, especially in the Flanders area with its high water table, sandbags covered with soil had to be built up at the side of the trenches to give height to the trench and protect the occupants from incoming fire. Also wooden duckboards were laid across the floor of the trench to aid movement and in an effort to keep feet dry. However in bad weather trenches still flooded and soldiers found themselves wading through knee deep water. Prolonged immersion in water led to the dangerous condition of trench foot which incapacitated many soldiers.

Time Expired

On 5 May 1917 my grandfather, now with the rank of Colour Sergeant and holding the appointment of Company Quarter Master Sergeant proceeded on a month’s leave to the UK, his first home leave for two and half years.

On enlistment Territorial Force recruits were engaged for up to four years. After this period the soldier would ‘Time Expire’ and could leave the service or extend it in further blocks of four years. On 1 January 1916 this was to change; the Military Service Act (MSA) came into force imposing conscription for the first time. It also meant that any ‘Time Served’ Territorial soldiers could be compulsory re-enlisted if they filled the criteria of the MSA Act. They would then be required to serve for the duration of the war.

This is exactly what happened to Frank, whilst in the UK he was re-engaged into the colours at Preston and was paid a bounty of £5 before returning to his unit in France.

On 16 May whilst Frank was on home leave in England 127th Brigade Headquarters issued Order No. 15 advising all units that the brigade and attached troops consisting of 1/2nd (East Lancashire) Field Ambulance, 427th Field Company Royal Engineers and 431st Company Divisional Train, would move to the Ytres, Neuville-Bourjonval, Ruyaulcourt and Bertincourt areas preparatory to taking over a brigade front east of that area on the 19th.