Flt. Lt Ronald Walker... The Wigan Pilot Murdered by the Gestapo.

Introduction

In June 1944, at the height of the Second World War, Flight Lieutenant Ronald Walker failed to return from a bombing mission over Germany. It wasn’t until March 1945 that his parents received official notification of his death, and another two years before the full story of his fate finally emerged.

Beech Hill Born

Ronald Arthur Walker was born 9 October 1922 at 170 Thicknesse Avenue, Beech Hill, Wigan, the eldest child of Horace Thomas Walker and Ethel (nee Woodhall). He was baptised at St. Andrew’s church in Springfield seven weeks later on 26 November.

His father Horace was a veteran of the Great War, having served three years on active service in the Royal Artillery. He worked as a rent collector for Wigan Council and during the Second World War was a volunteer air raid warden.

Beech Hill was part of St. Andrew’s Ecclesiastical Parish and in 1940 a wooden mission hut was built on the corner of Beech Hill Avenue and Netherby Road. It was the daughter church of St. Andrew’s for religion purposes.

St. Anne’s Parish was formed in 1947, and a new church was built in Beech Hill Avenue, opening in 1953. Revd. John Lawton, the curate of St. Andrew’s was appointed Priest in charge, and Ronnie’s father become church warden and treasurer.

Horace Walker (right) during a post war St. Annes walking day procession

Ronald’s mother Ethel was a local girl, living at 6 Buckley Street before her marriage to Horace. Her family had moved from nearby 300 Gidlow Lane a few years previously. She was a trained tailoress.

Ronnie, as he was known by friends and family attended Beech Hill Council School from 1927 to 1934. He then moved up to Gidlow Senior School, there he won a scholarship to Wigan and District Mining & Technical College where he studied engineering.

On leaving the college he became an apprentice at Leyland Motors. Ronnie was a keen swimmer and as a first aider was attached to Beech Hill First Aid Post. He was to have two younger siblings, Dorothy born in 1922, who trained to be a nurse at Walton Hospital in Liverpool, and Alan born in 1931.

Enlisting

On his 18th birthday, 9 October 1940, Ronnie stopped off at a recruiting office on his way home from work at Leyland Motors and enlisted into the Royal Air Force, volunteering for aircrew. Ever impatient to serve his country, he wrote to the Air Ministry a few months later and asked them to hurry with his application.

He finally received his call up papers in May 1941, accepting him into the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve as NCO aircrew. After his initial military recruit training he travelled to the USA for pilot training, gaining his wings in 1942 at Craig Field Air Base in Selma, Dallas County, Alabama. During the war 1,393 RAF cadets passed through the facility to earn their wings.

Flt. Lt. Ronald Walker, with his parents and siblings whilst on leave at 170 Thicknesse Ave, Beech Hill

170 Thicknesse Avenue today

83 Sqn RAF crest

Whilst at RAF Wyton Ronnie gained a commission and was promoted from Sergeant to Pilot Officer on probation. On 1 June 1943 he was promoted again to Flying Officer. On 18 April 1944 the squadron relocated to RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire.

The Fateful Mission

On 6 June 1944 Ron, now with the rank of Acting Flight Lieutenant, was flying his crew over Cherbourg in Normandy supporting the D-Day landings. Two weeks later on Wednesday 21 June 1944, they were briefed on a mission to bomb the synthetic oil refineries at Wesseling, an industrial city that lies on the River Rhine in Germany, between Cologne and Bonn.

Lancaster bomber photographed on the Wesseling raid

Ron’s aircraft, numbered ND551 and with the code letter ‘V’ for Victor, was one of ten that took off at 23:18 hours from RAF Coningsby, it was their 45th operational sortie. Over the Dutch coast, en route to the target, the bomber stream was intercepted by German night fighters. Ronnie’s crew managed to fight off one attack but the evasive action took them off course.

At 01:25 hrs on the 22nd of June, whilst they were trying to rejoin the bomber stream at 16,000 feet they were attacked and shot down by a German night fighter patrolling five miles south of the Dutch city of Eindhoven.

The aircraft exploded in mid-air, the wreckage falling in open countryside a couple of miles south of the small town of Valkenswaard. Ron was thrown clear by the explosion but the six other crew members all perished.

V for Victor had been unlucky enough to encounter Luftwaffe ace, Hauptmann Heinz Wolfgang Schnafer flying a Messerschmitt 110. It was his 80th kill to that date, and his first of four that night. Schnafer had taken off from Sint -Truiden (St Trond), 45 miles to the south in Belgium and was patrolling the Eindhoven area. Before the end of the war Schnafer was to claim 121 kills in 164 missions, making him the highest night fighter ace in the history of aerial warfare. He was nicknamed the ‘Spook of St. Trond’.

Hauptman Heinz Wolfgang Schnafer, Luftwaffe night fighter ace.

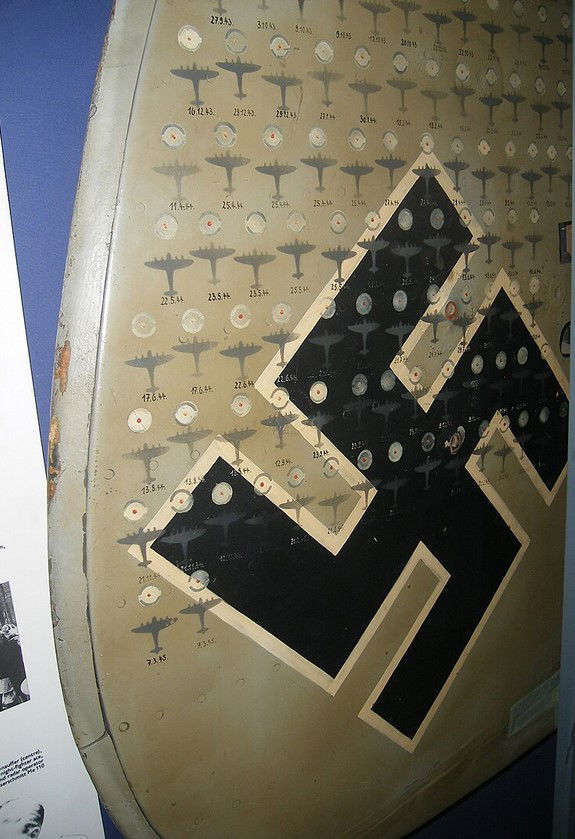

On display at the Imperial War Museum in London. The port side tail fin of Schnafers ME110 with his record of kills. The date 22.6.1944, the day he shot Ronnie's aircraft down, can be seen just to the left of the Swastika.

Evader

Ronnie later related that he had no recollection of exiting the aircraft following the explosion and must have been unconscious during his fall from which he miraculously survived. After gaining consciousness on the ground he found his only injuries were bruises on his back and right leg.

In World War Two all allied airmen were taught the art of escape and evasion. Whether they had bailed out of their aircraft, crash landed or escaped from captivity, their aim was to reach a neutral country from where they could be repatriated back to the UK and rejoin the war effort.

Depending on the circumstances and location, the choices were via Denmark or a Baltic port in Germany and onto Sweden. To Switzerland via Germany or France or as in most cases via France to Spain, then onto Gibraltar and home to the UK.

The Dutch Resistance had an escape line network set up that smuggled Jews, resistance members on the run from the Gestapo, and downed Allied airmen into Belgium, then down through France to Paris. It was known as the ‘Dutch to Paris Network’. From Paris the French resistance escorted the evaders south over the Pyrenees and on to Spain. Ronnie was now an evader and started to walk west in the direction of the Belgian border. It was the start of a 600 mile journey to a neutral country.

After a few miles, near the small town of Bergeijk, he came across a farm belonging to Jaques Martens where he sought assistance. The farmer’s wife called over a farm worker by the name of Bas van de Aaist, who was working in a nearby field. Bas was really a schoolteacher, but as a member of the Dutch Resistance was working on the farm in order to hide his real identity from the Germans, he concealed Ron in a cornfield until nightfall.

By coincidence another Resistance colleague, Walter de Vries, arrived at the farm that day, and it was de Vries that ended-up taking charge of the RAF pilot. Ronnie, dressed in civilian clothes, accompanied Walter by bicycle to his house in Nuenen, some thirteen miles away to the east of Eindhoven. He was then passed along the underground chain, spending a week with a farmer by the name of Verthofen. Here he met up with a 26-year-old Australian by the name of Jack Nott.

Flying Officer Jack Nott. Royal Australian Air Force

Jack was a bomb aimer with No 77 Squadron based at RAF Full Sutton near York and had a similar story as Ronnie to tell. His Halifax bomber had been shot down over St-Oodenrode near Eindhoven on the night of 16/17 June, on a raid to the Sterkade/Holten synthetic oil plant on the Ruhr. Five of his comrades were killed, the other two were captured and made prisoners of war.

(There are slightly differing accounts regarding the order in which Ronnie and Jack were transferred along the escape line, but it is generally accepted that the following events occurred which ultimately ended their bid for freedom).

Eventually it was time to move on along the escape network and over the border into Belgium. On 29 June the two airmen, accompanied by de Vries and two other underground members began their journey by bicycle to the Eindhoven suburb of Waarle. Leading the way was Walter de Vries, followed at around 30-yard intervals by Ronnie, then a second resistance worker, then Jack Nott, with the third Dutch Underground man bringing up the rear.

They were safely deposited at the house of Frans van Dijk, who was hiding two Canadian airmen at the time. Frans was the head of the resistance group in Waarle and he provided each of the airmen with false Dutch identity cards. Next stop for Ronnie and Jack was the home of the four van Moorsel sisters who lived at Stationsstraat 43, opposite the railway station in Waarle.

That evening they were taken by two policemen, who were working for the Resistance, by police car to the home of Miss Leonarda van Harsell (known as Leonie) at 59 Heuvel, in Tilburg. Leonie had been a medical assistant prior to the war. She along with her father Henry, a butcher, and sister Elizabeth (known as Beppie) were active members of ‘Group Peter’ of the Dutch Resistance, which was concerned with helping evaders. Leonie was tasked with finding safe houses and the transportation of those on the run.

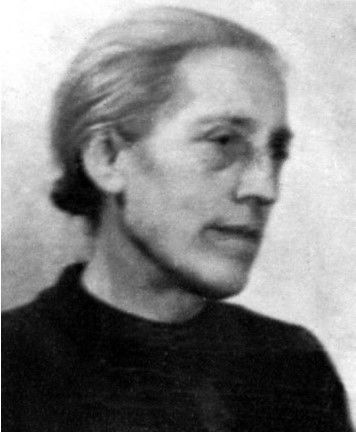

Leonie van Harsell member of the Dutch Resistance

The van Harsell’s were already harbouring a Canadian flyer by the name of Roy Carter, who was a member of 431 Squadron based at RAF Croft in Yorkshire. Roy was the navigator of a Halifax bomber that had been shot down on its seventh mission on the night of 16/17 June near Nistelrode. All the crew managed to bail out except the pilot, but two did not survive the parachute jump. Two others became evaders but one was later captured.

Flying Officer Roy Carter. Royal Canadian Air Force

The plan was to next move the airmen by police car driven by a Dutch policeman known as ‘Jante’, but they had trouble fitting the heavy set Carter in the vehicle. Instead he travelled by bicycle with Leonie van Harsell and her sister Beppie to 49 Diepenstraat in the town of Tilburg, arriving just before Ronnie and Jack. The house in Diepenstraat belonged to spinster, Jacoba Maria Pulskens, known in the resistance as ‘Aunt Coba’.

Jacoba was born 26 May 1884 in Tilburg, at the age of 18 she left for Antwerp in Belgium to work for a Jewish diamond merchant. On her eventual return to her home town she worked first as a cleaner in a school, then as a cleaner in a building belonging to the Public Works Department.

Jacoba Pulskens in 1943

After the German occupation of her homeland she volunteered to shelter Jews who were avoiding deportation to the concentration camps. She later took in members of the Dutch Resistance but after a traitor infiltrated the underground network her house was considered unsafe to use. Eventually though she agreed to harbour Allied pilots who were evading capture.

Shot in Cold Blood

Between 3am and 4am on Sunday 9 July the police car driven by Jante that had transported Ron and Jack to Diepenstraat the previous evening was stopped by a Wehrmacht (German Army) unit at Moergestel, just to the east of Tilburg. The policeman, two Dutch civilians and the two Canadian airmen that Ron and Jack had met earlier at the home of Frans van Dijk were arrested.

The two Canadians were handed over to the Luftwaffe at Gilze Rijen Aerodrome near the city of Breda. A phone call was made to SS Hauptsturmführer Hans Ernst Harders, the head of the Dienstelle (office) of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD- Security Service of the SS) at 's-Hertogenbosch, a town twelve miles to the north east of Tilburg. Their purpose was to track down and suppress the Dutch Resistance Movement. He was requested to send a squad of men to Moergestel to pick up the three Dutchmen.

Following the interrogation of the captured police driver by SS- Oberscharführer Albert Rosenor, the whereabouts of Ronnie, Jack, and Roy was revealed. Harders organized a raid to capture the airmen. The raiding party of seven men, accompanied by the manacled Jante, left ‘s-Hertogenbosch in three cars and drove to Diepenstraat in Tilburg.

Under interrogation Jante had not given a house number, just revealing that the airmen were hiding in a house next door to a shop in Diepenstraat. This meant that two properties had to be searched. One driver, SS-Oberscharführer Karl Johannes Brindle, guarded Jante the policeman. Another driver, Rottenführer Eugene Emil Rafflenbeul stayed with his vehicle in readiness to transport the captured airmen back to ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

The leader of the raid SS-Untersturmführer Paul Hardegan and the other four members of the party spread out covering all avenues of escape. SS-Oberscharführer Karl Kramer and SS-Oberscharführer Albert Rosenor searched one house without success.

This left Karl Paul Schwanz, a former police driver and member of the Nazi Party and Michael Rotschopf, an Austrian and former secretary in the security police to search 49 Diepenstraat. Kramer and Rosenor positioned themselves at the rear of number 49 to stop anyone trying to escape. Between 11:15 and 11:30 am Aunt Coba went to the door of her home, in answer to someone ringing her doorbell. Schwanz was the first to force entry past Coba followed by Rotschopf carrying a machine pistol. She followed them into the house in time to see the three pilots with their hands raised, being backed through the kitchen door.

In the yard at the rear of the house Rotschopf shot all three airman with bursts from his 9mm MP40 machine pistol which held a magazine of 32 rounds. One report says that witnesses from neighbouring houses saw one of the injured airmen, (possibly Roy Carter) try to escape back into the house but was shot down by Rotschopf in the kitchen doorway. On hearing the firing Kramer and Rosenor climbed the wall at the rear of number 49 to join their comrades in the back courtyard.

Coba Pulskens with unknown persons in the yard where the airmen were murdered

Hardegan instructed Jacoba to cover the bodies with a sheet. In a last act of defiance before she was arrested, she used a Dutch flag she had kept for the day the Netherlands was liberated, to cover the airmen.

Before the bodies were taken away to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Tilburg they were photographed by an Inspector in the Ordnungspolizei (Civil Police). At the hospital the bodies were examined and photographed again by a Dr. Borman who estimated that collectively the airmen had been shot more than one hundred times. If so that meant Rotschopf must have reloaded his sub machine gun twice with fresh magazines. From the hospital the remains of the three airmen were transported to Vught Concentration Camp, near ‘s-Hertogenbosch and cremated in the ovens.

Captivity

Beside Coba, Leonie van Harsell, Jante the driver and four other Resistance members were arrested and detained. Sjef van Eerdewijk and his sister Anna who lived next door in the grocery store and had supported Coba in her work, were also arrested, but after interrogation were eventually released.

Sjef van Eerdewijk, Jacoba's neighbour who was arrested after the shootings

Coba and Leonie were to meet up again, firstly at the Geisellager (hostage camp), located in a former seminary in Haaren, some seven miles east of Tilburg. Then again at nearby Vught Concentration Camp. Here Jacoba was able to relate the story of the murder of the airmen to Leonie.

Vught Concentration Camp at s'Hertogenbusch, Holland

With British and Canadian forces advancing from the west, Camp Vught was evacuated in September 1944, Jacoba and Leonie were transferred to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in Germany, 65 miles north of Berlin.

Ravensbruck Concentration Camp, Germany

Leonie was transferred once more to a labour camp at Giesing, 360 miles to the south, in the suburbs of Munich in Bavaria. Giesing was a satellite camp of the infamous Dachau Concentration Camp. The camp records show her prisoner number as 123105 and that she arrived at Giesing on 13 November 1944.

She was put to work in the Agfa camera factory whose production lines had been taken over for the production of fuses and ignition timing devices for bombs, artillery shells, and V-1 and V-2 rockets. With the war coming to an end production ended 23 April 1945 and the women were marched south toward Austria. However their German guards soon surrendered to advancing American forces near Wolfratshausen, south of Munich. On release Leonie returned to her life in Noord Brabant Province, she died 3 May 1998 in Waalwijk, aged 78.

Women prisoners working on a munitions production line at the Agfa factory at Giesing, Bavaria.

Coba Pulskens wasn’t to be as lucky, she perished, aged 60, in the newly constructed gas chamber at Ravensbrück in February 1945, and her body cremated. It was reported by other prisoners that she had voluntarily taken the place of a woman prisoner who had young children. Jacoba was just one of over 90,000 women who died in Ravensbrück during the war.

The crematoriums at Ravensbruck shortly after liberation in May 1945

Reprisals Against Airmen

As the tide of war turned against the Nazis and German cities suffered from repeated air raids, anger grew amongst the civilian population. As early as March 1940, Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s right hand man and Deputy Führer, issued an order that enemy parachutists were to be immediately arrested or rendered harmless. The Nuremburg War Trials later translated ‘rendered harmless’ to mean ‘liquidated’.

Joseph Goebbels the Minister of Propaganda for the Third Reich gave orders in 1943 that radio and print publications eliminated the words ‘pilot’, ’air crew’, and ‘plane’ from official vocabulary. Instead in the Volkischer Beobachter (the official Nazi newspaper), and in his propaganda broadcasts on state radio Goebbels referred to Allied aircrew in derogatory terms such as ’Terrorflieger' (terror flyers) ‘Mordfliegern’ (murder flyers), ‘Luftgangstern’ (air gangsters), and even ‘Lufthunnen’ (air barbarians)’. The purpose of this was to demonize the airmen and change civilian feelings about them.

In July of that year Germany’s Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (high command of the armed forces) banned military funerals for Allied airmen. A few weeks later an order from Heinrich Himmler, Reichfuhrer of the Schutzstaffel (SS) forbade the SS and police forces from intervening in any local confrontations between civilians and airmen who had survived parachute landings.

The result was the murder of hundreds of allied airmen by civilian lynch mobs. They were paraded in the streets and shot or beaten to death with spades, metal bars, sticks and rocks. The lucky ones who were captured by the military had to endure stoning attacks and beatings by the civilian population in the streets and at railway stations before they reached the relative safety of the prisoner of war camps.

After the war many civilians were aprehended, tried for murder and sentenced to death by British and American Courts. But many more escaped retribution.

Field Marshal Keitel wrote down that Hitler decided, at the end of May 1944, that the army should shoot to death downed Allied airmen in certain cases without even so much as a drumhead court-martial.

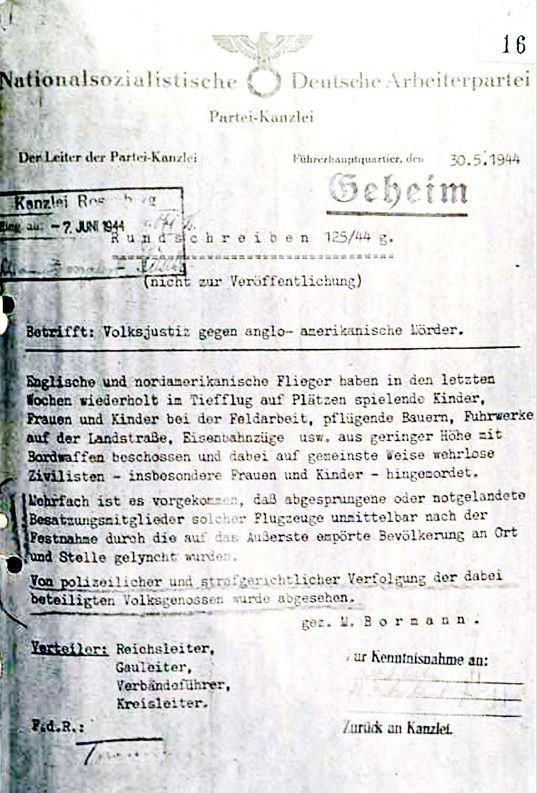

Hitler's party secretary Martin Bormann sent out a secret circular on 30 May 1944, its contents were to only be transmitted to the local Nazi party leaders verbally. The circular accused allied airmen of murder by flying low and targeting defenceless women and children in playgrounds and parks, and farmers on their tractors in the fields. In a veiled attempt to encourage civilians to take the law into their hands it emphasized that so far any civilians who had taken part in the murder of captured airmen hadn’t been prosecuted by the German authorities.

The circular by Martin Bormann dated 30 May 1944

On 4 July, 1944, the police received secret orders which amounted practically to an order to kill all allied airmen, without regard for the circumstances of the case. This was just five days before the murders of Ronnie, Jack, and Roy. It begs the question of how much the perpetrators of the killings were influenced by orders from above.

Brought to Justice

Those believed to be involved in the murders in Tilburg were tracked down and tried before a British Military Court under the jurisdiction of British Law. The trial was held at the Jugendheim (youth centre) on Fürstinstrasse in Steele, a suburb of Essen in Germany. It commenced on 11 June 1946 and was to last sixteen days.

The Court consisted of six members, a President and a Judge Advovate who were both from the RAF, three Army officers and an officer from the Royal Australian Air Force. The accused were defended by German lawyers.

The ten defendants, nine Germans and one Austrian, were charged with committing a war crime in that they at Tilburg on the 9th of July 1944, in violation of the laws and usages of war, were concerned in the killing of a member of the Royal Air Force, a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force and a member of the Royal Australian Air Force.

All ten pleaded not guilty, Leoni van Harsell, the resistance worker and survivor of Ravensbrück testified as to the events of 9 July, the court being permitted to hear evidence from a secondary witness as the primary one (Aunt Coba) was no longer alive.

Other witnesses testified seeing some of the accused in the vicinity or in the property in Diepenstraat at the time of the murders. Of the ten, four were convicted and sentenced to death, these were Michael Rotschopf aged 26, Karl Paul Schwanz aged 49, Albert Erich Ernst Rösener aged 35, and Karl Cremer aged 37.

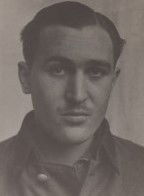

Michael Rotschopf the killer of the three airmen

Karl Cremer one of the condemned quartet

The Court acquitted five of the defendants, Hans Ernst Harders, Franz Schonfeld, Karl Herman Otto Klingbeil, Karl Johannes Brendle, and Eugen Emil Rafflenbeul due to lack of evidence and they were released. One other, Werner Koeny was acquitted as it was proved he was on convalescent leave at the time.

Absent from the trial was S.S. Untersturmführer Paul Hardegan, the leader of the raiding party. His whereabouts were unknown, he was already a wanted man for ordering the execution of another British airman, Flying Officer Gerald Hood who was murdered in Almelo.

SS Untersturmführer Paul Hardegan who escaped justice.

Hardegan made his escape just prior to the liberation of the Noord Brabant Province by British troops. He was last heard of in the Utrecht area, but by the time he had been sentenced in his absence, Hardegan had vanished for good. Evidence suggests that he was smuggled out of Europe and began a new life under a new identity.

The four who were found guilty were hanged the following year at Hameln (Hamelin) prison on Friday 5 September 1947 by Albert Pierrepoint, the famous English hangman, with the help of his assistants Edwin Roper and RSM Richard O'Neill. Pierrepoint hanged 191 male and ten female war criminals at Hameln, and in his career he carried out over 450 executions.

Pilgrimage and Memorials

After the war had ended Ronnie’s father Horace strove to discover what had happened during the last two weeks of his son’s life. This culminated in a visit to Holland and the site where Ron was murdered. He painstakingly collected his findings in an album, which passed into the hands of his daughter Dorothy who was just 20 when her brother died.

On 2 February 1947, a memorial to pay homage to Coba was unveiled on the corner of Diepenstraat and Jan Steenstraat in Tilburg.

The Coba Pulskens memorial on the corner of Diepenstraat and Jan Steenstraat, Tilburg, Holland

The inscription on the memorial reads:

MARY MOTHER OF MERCY

IN HONOR AND REMEMBRANCE OF JACOBA PULSKENS

AND ALL FALLEN CITY FELLOWS

FROM THE RESISTANCE

2 FEBRUARY 1947

In the late 1970’s Ron Low who had served as a Leading Aircraftsman in 83 Squadron during the war began compiling his former unit’s roll of honour. In 1982 he asked Dutch researcher Jan van den Driesschen to investigate in more detail the events surrounding the death of Fl. Lt Ronald Walker DFC. Jan asked an acquaintance, Rinj Elshout to assist. Rinj lived in Noord-Brabant Province and was familiar with all the locations where the fateful events occured.

Together the pair discovered that Anna van Eerdewijk was still alive and living at the same address, next door to Coba Pulsken’s house in Diepenstraat in Tilburg. However, her brother Sjef had now died. When Jan met with Anna it was discovered that the Dutch flag had survived with a relative of Coba, who then agreed that the flag should go to England to form part of a memorial.

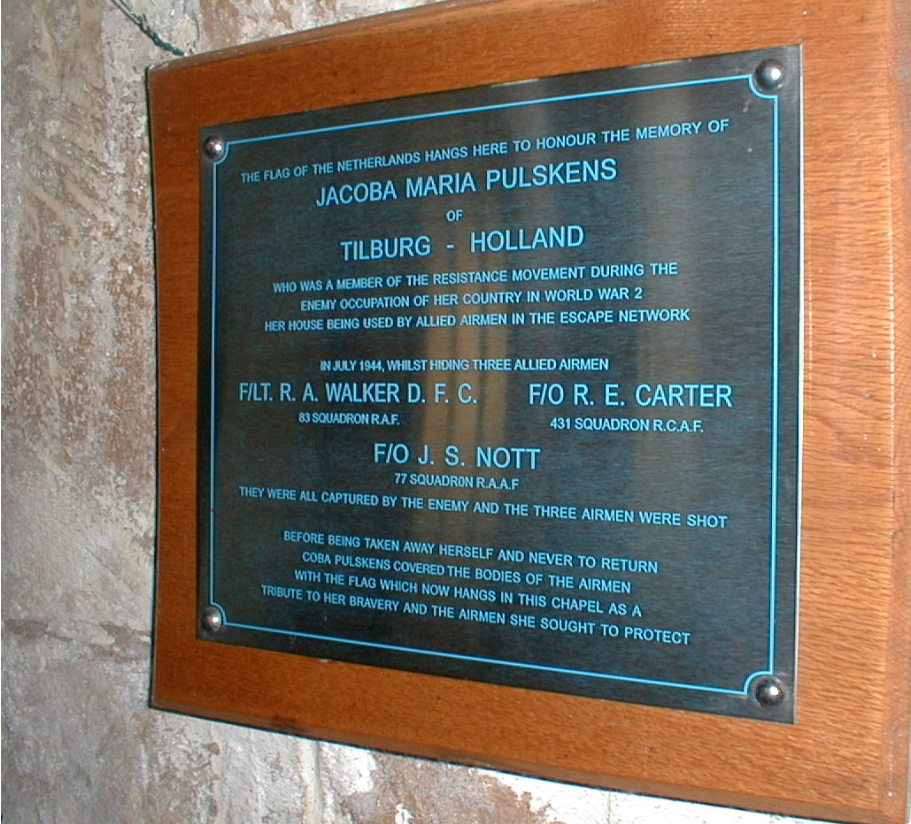

In consultation with Dorothy Walker and her brother Alan, it was agreed that the flag, and a plaque recalling the heroism of Jacoba Pulskens, were to be placed in the Airmen’s Chapel at St Michael’s Church at Coningsby, Lincolnshire, which is dedicated to 83 (Pathfinder) Squadron.

St. Michael's Church, Coningsby Lincolnshire

Ron Low, representing the 83 Squadron Association, invited Ron’s sister Dorothy to travel to Holland to receive the flag and bring it back to Lincolnshire. On 8 May 1983, the dedication of the flag and the plaque took place at Coningsby.

Representatives from the families of all three murdered airmen joined those from the Pulskens family, Coba’s neighbour Anna van Eerdewijk, civic leaders from Tilburg and around 100 members of the 83 Squadron Association for the event.

The Dutch flag in the Airmens Chapel in St Michael's church Coningsby

The plaque in the Airmens Chapel dedicated to Jacoba Pulskens and the three murdered airmen.

On 27 October 1984, during the fortieth anniversary of the liberation of Tilburg, a memorial boulder was unveiled in Freedom Park to commemorate Coba and the three airmen. Every year on Liberation Day a commemoration is held at the boulder by children from a nearby school that has adopted the monument.

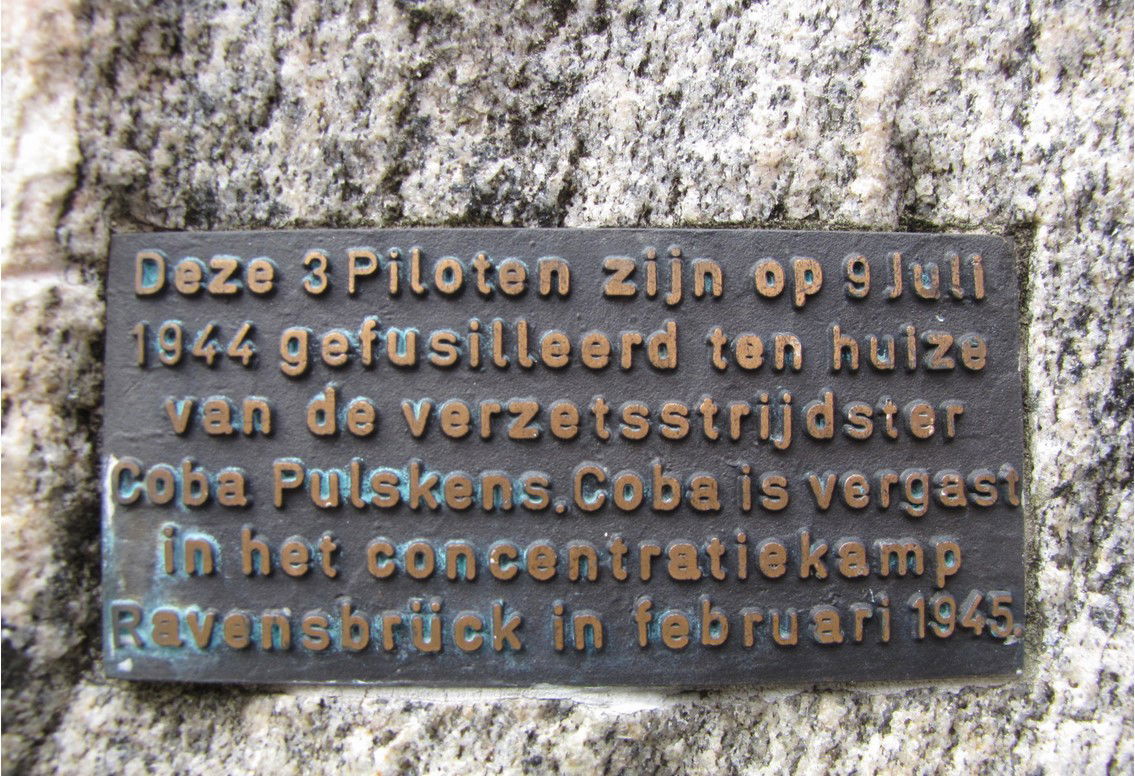

The Tilburg Boulder Memorial

Brass plaque on the Tilburg boulder.

The inscription on the plaque reads :

These 3 pilots were executed on July 9 1944 at the home resistance fighter Coba Pulskens. Coba was gassed in the Ravensbruck Concentration Camp in February 1945.

That same day a delegation from the Royal Air Force presented a plaque to the town, which was placed in the chapel of Maria Ter Noord (Our Lady in Distress) which had been built in the centre of the town after the war. A second plaque was also provided for display in the hall of the Public Works office in Tilburg where Coba had once worked.

Recognition

Whilst on the run from the Germans Ronnie was unaware that on 27 June 1944 he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). On 13 June 1946 he was posthumously mentioned in Dispatches for his efforts to evade capture and return to duty.

Distinguished Flying Cross

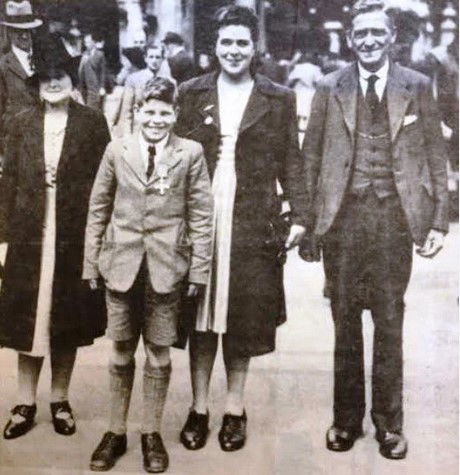

In 1946 Ronnie’s parents Horace and Ethel, accompanied by his sister and brother, Dorothy and Alan travelled to London to receive the DFC on behalf of their son from King George VI at Buckingham Palace.

Ronnie's parents, Horace and Ethel with sister Dorothy and brother Alan after receiving his DFC from King George VI. Alan is proudly wearing his brother's medal.

Coba Pulskens was posthumously nominated for the American Medal of Freedom for assistance to Allied crew members. She was credited with helping 21 airmen escape back to Allied lines.

American Medal of Freedom

Because the remains of the three airmen were never found, they are listed officially as missing in action. Their names are recorded on the Runnymede Memorial to the Missing in Surrey. Ronald Walker is on Panel 203, Roy Carter on Panel 245, and Jack Nott is on Panel 257. Ronnie is commemorated on Wigan Cenotaph and their are plaques in St. Annes church and Beech Hill Primary School in his remembrance also.

Runnymede Memorial to the Missing, Surrey

Ronnie’s crew are buried in Eindhoven (Woensel) General Cemetery, they are:

Navigator, Flt. Lt Norman James Cornell DFC, aged 33. Plot KK80.

Wireless operator, Flt. Sgt Reginald Charles Bailey DFM, aged 22. Plot KK77.

Flight Engineer, Flt. Sgt. Harold Edward Houldsworth DFM, aged 20. Plot KK 92.

Bomb Aimer, Flt. Lt. John Hall Wells DFC, aged 21. Plot KK 79.

Air Gunner, Warrant Officer David Richard Kelly DFM. Plot KK 81.

Air Gunner, Flt. Sgt. Charles Robert Taylor DFM, aged 20. Plot KK 78.

Woensel General Cemetery, Eindhoven, Holland where the crew of V for Victor are buried

The Flag

In 2019, 75 years after the death of Ronnie Walker, local historian Tom Walsh accompanied Tom Morton, a representative of St. Anne’s church, on a journey to St. Michaels church in Coningsby. There they were loaned the Dutch flag that had covered the airmen’s bodies, it was brought to Beech Hill and put on display at St. Annes Church during a memorial service.

Local historian Tom Walsh with church warden Michael Gaskell, Tom Morton and Keith Buckley with the Dutch flag in St. Annes church.

Owing to Covid travel restrictions that came into force shortly afterwards, the flag was to stay at St. Anne’s church for several months, before finally being returned to its home in the Airman’s Chapel at Coningsby in 2020.

The Dutch flag on display at St. Annes church, Beech Hill.

Lest We Forget.

Graham Taylor 2024

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tom Walsh for inspiring this story with his article ‘The Flag’, published on the Wigan Local History & Heritage Society website and providing copies of photos and documents. Also David Eaborn, great nephew of Ronald Walker for providing Walker family information.

Primary Sources

Aircrewremembered: Archive Report, Allied Forces. Researchers Ralph Snape and Traugott Vitz

Legal-tools.org – trial transcripts

Shot in Cold Blood, Part 1 Nov 2012, Part 2 Nov 2014 by Fred Carter. Researchers Jan van den Dreisschen and Ron Low Word Press

Other Sources

Ancestry.co.uk

Capital Punishment.org, chapter 6 Airmen

Concentration Camp Records Germany 1939-1945

Database, Henk Welting

Dutch Paris Blog

Find My Past

Historynet, article by Zita Ballinger

Fletcher Huygens Institute, Netherlands

Lancashire Online Parish Clerks

Lincolnshire Lancaster Society

National Archives

The Flag, article by Tom Walsh

Wigan Observer articles1982 & 2017

Wikipedia

WW2 Netherlands Escape Lines