19th Century Housing in Wigan

At the end of the nineteenth century Wigan had the highest rates of overcrowding of all the large Lancastrian towns and, some of the country's worst housing conditions.

Already houses built early in the century were being forcibly demolished. How had such housing conditions developed ?

Who originally built and owned the houses; for whom were they built; how effective were local bye-laws in controlling house standards; and, how did changes in demand and supply for housing affect the towns' social development?

Wigan was an ancient borough town with strong cotton manufacturing interests,

BUILDING PRACTICES AT THE END OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

By 1801 Wigan had emerged from a period of economic stagnation to become a bustling cotton and linen manufacturing town of 11,000 people. Approximately 60 per cent of all family heads were involved in textile manufacture, 40% as handloom weavers. Only 7% were now occupied in traditional metal-working trades with a further 7% in coal mining, an industry soon to expand.

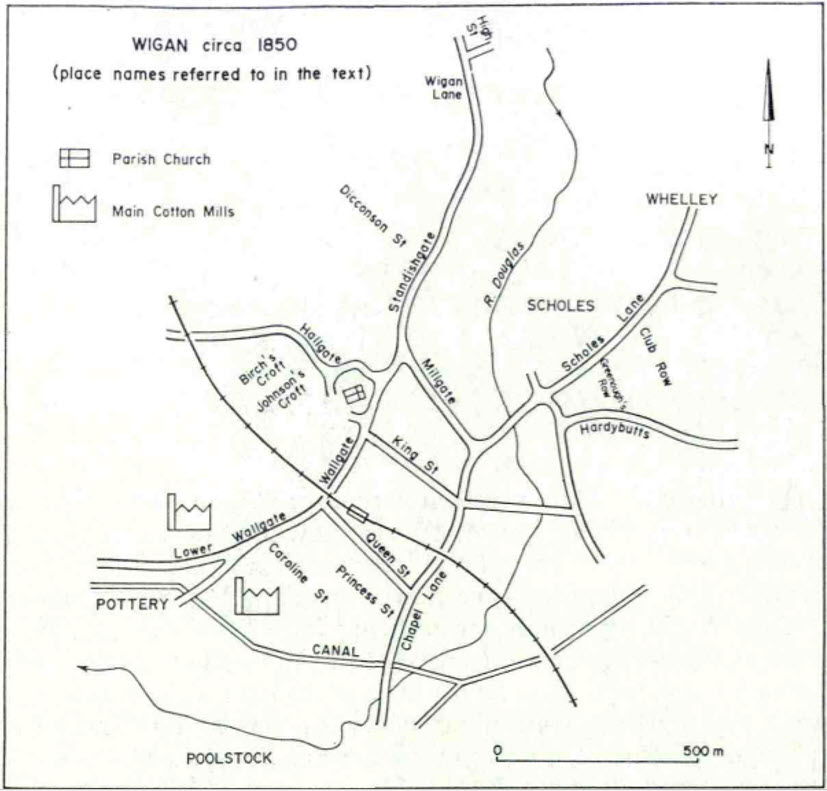

This economic resurgence produced a house building boom in which burgage plots particularly in Scholes and along Standishgate were built over (see map).

The Land Tax returns (1796, 1806, 1807 and 1819) and the rate book of 1812 for Wigan, together with title deeds of property compulsorily purchased by the corporation, give an outline picture of WIGAN circa 1850 (place names referred to in the text)

Title deeds indicate an active land market in the 1780 and 1790, with land often bought and sold several times over just prior to building. No single landowner dominated in this process, there being 353 property owners listed in the 1796 Returns with only 36 having property taxed at over £1 (the total tax for Wigan was £160). The two most important land and property-owning families, the Baldwins and the Hodsons, each paid only about 5 per cent of the total assessment, and much of their land was in the outer parts of the borough, away from the built-up area.

Many property developers were in fact small-scale manufacturers and shopkeepers who concentrated their house building on the burgage plots behind their own houses and workplaces. This is indicated in the land tax returns where, after listing an owner's name, occupants are often declared as 'himself or 'himself and others': 144 of the 353 owners fall into this category. Few of these landowners built more than eight houses at a time one, two or three being most common and there were comparatively few, as compared with the mid-nineteenth century situation in Wigan, who owned houses away from their immediate neighbourhood. In 1811 at least 24 (probably 30 plus) out of the 55 people who owned property in Scholes also lived there.

HOUSING SUPPLY CHANGES IN WIGAN

The local and small-scale development of housing in Wigan was fast being overtaken. The rate book of 1812 clearly distinguishes court (burgage plot) houses which were now commonly listed in runs of ten and more. The longest runs of such identically rated houses were usually owned by cotton or linen manufacturers: in Scholes there was Greenough's Row, 37 houses owned by Peter Greenough, a cotton and linen manufacturer of Standishgate; in Hallgate there was Birch's Croft, 20 houses belonging to Thomas Birch, a bleacher, of Gidlow House, and Johnson's Croft, another 20 houses owned by William Johnson, a cotton manufacturer of Wigan Lane.

These were cottages specifically designed for handloom weavers and often built as back-to-backs with a short flight of outside stairs leading to a living-room which measured approximately n' X n', above which there was the sleeping area and below which, in a half-basement, a loom shop. On Princess and Queen Streets, off Wallgate, larger through cottages were built but the same room design was used. Close by was the small Princess Street spinning mill. This close juxtaposition of loom shop and spinning mill had become a common sight in Wigan.

The King, Queen and Princess Streets development of the early 1790 was the first major break with the process of the piecemeal infilling of burgage plots. Of these streets, laid out parallel to each other between Wallgate and Chapel Lane, King Street was for high-class commercial and residential development only, the others for artisan housing.

The Queen-Princess Street area (then known as Markland and Further Markland fields), about three acres in extent, was acquired in 1789 by James Ditchfield, a local ironmonger, on life lease on payment of a £50 annual rent. This was to be paid in turn by people to whom Ditchfield sold individual plots. But in September 1794 only £15 of the total rent had been discharged and by 1800, if not before, James Ditchfield was declared bankrupt.

The remainder of the land was auctioned off in rectangular plots of approximately 250 square yards each. Most of those buying lots from Ditchfield in the 1790’s were small masters from a wide variety of trades currier, maltster, butcher, watchmaker, and so on who lived and owned small amounts of property in other parts of Wigan.

James Caterall of Millgate, variously described as ropemaker, shoemaker and yeoman perhaps developed his property interests most successfully. In 1795 he bought 566 square yards of land in Princess Street on which he built seven houses. By 1806 he had also built runs of five and twelve court houses in Scholes and by Working Class Housing the time of his death in 1817 he owned over 40 houses mainly in Scholes. Men like Caterall often raised their capital through local manufacturers such as Roger Anderton of Scholefield Lane or local attorneys such as Robert Morris, but by 1800 building clubs became an alternative means of financing buildings.

EARLY BUILDING SOCIETIES

The Land Tax assessments for Wigan in 1806 are very suggestive on the activities of building clubs: a number of like-valued properties are listed consecutively but are owned singularly, in pairs or sometimes in multiples of four. Several are occupied by their owners of whom there is often no mention in other records such as burgess lists and early directories. In one such listing, 50 houses, each valued at 4d. (house valuations varied from about gd. to 6s.) and built before 1796, can be located on the High Street off Wigan Lane, behind Penson's cotton mill; 24 houses in a second listing and built between 1799 and 1806 were each valued at one shilling, and were located close to Leigh's Flint Mill, probably in the Pottery. Unfortunately, no related title deeds survive but the assessments and title deeds provide direct evidence of the activity of the Scholes Building Society founded probably in or before 1802 when eight cottages known as Club Row were built on the western side of Vauxhall Road.

Between 1802 and 1810 another 60 cottages were built for the 20 or so subscribers to the club each of whom bought three shares for which he was allocated three adjacent cottages on the casting of lots. On the termination of the society in 1810 the land and the three cottages were conveyed to each subscriber, subject to a yearly ground rent which could be paid off in a lump sum if desired. The cottages, valued at 4d., were specifically built to rent to handloom weavers: according to the 1811 census enumerators' schedules only five cottages were not so occupied.

The rate book of the following year also indicates that in many cases the land behind these cottages was built over with groups of four to eight back-to-back cottages. The owners were neither artisans nor small masters but manufacturers and farmers who saw the building club purely as an alternative means of investment.

Indeed, of the three house owners identified on the High Street one was Robert Morris, the second Charles Kerfoot who later owned a run of 37 cottages (Kerfoot's Row) adjacent to Greenough's Row, the third, John Stopforth, a prominent local builder. Not surprisingly, capitalists such as those prominent in building some of the worst housing in Wigan over the next 20 years again often used building clubs as a major source of funding.

For example, in 1826 the land between Greenough's Row and Vauxhall Road was sold off in long narrow lots to Richard Bradshaw, corn dealer, Archibald Stuart, linen merchant and John Atkinson, joiner and builder, the first two being associated with the Scholes Building Club. In Archibald Stuart's case, land immediately behind his property on Club Row was acquired and using £500 advanced by the Wigan Building Society (founded 1822) he built 30 cottages, again primarily for handloom weavers. Bradshaw built 21 cottages, Atkinson another 20 or so, in all likelihood using the same source of funding. All these houses were compulsorily demolished by 1896.

MID-CENTURY SANITARY REFORM AND HOUSING STANDARDS

Despite its inherently well-drained site, Wigan was, in midcentury, considered to be one of the unhealthiest towns in the country and certainly far worse than most other towns of comparable size in Lancashire: the death rate in 1851 of 36 per 1,000 compared badly with 27 per 1,000 in the North West generally.

However, because of successful lobbying of both local ratepayers and Westminster by the Wigan Working Man's Association, a group supported by the local clergy, a somewhat reluctant borough council found itself having to operate the Public Health Act of 1848. The main effects were very limited: the death rate between 1866 and 1870 averaged 32.7 per 1,000. Bye-laws relating to privy construction were generally disregarded; the water supply and sewerage systems were only very slowly improved and cellar dwellings, supposedly banned, often remained. Attempts in the 1860 bye-laws to increase the thickness of house walls were effectively blocked by local building interests.

All that was required was that estate plans showing road lines and sewer depths and building plans showing drainage levels should be submitted. Even these were sometimes not complied with.

VICTORIA STREET, WALLGATE,

Built in the cotton factory boom of the late 1830’s, the houses were soon occupied by Irish immigrants, two families per house being common.

In Wigan between 1851 and 1871 there was a less noticeable improvement in housing standards if rateable value is a criterion. Following a short-lived building boom in the early fifties, house building fell dramatically not to recover until the mid-seventies, mirrored in Manchester, the centre of the cotton industry.

Between 1851 and 1861, for the first time in the century, outmigration from Wigan balanced immigration and in the following decade there was a net outflow of about 5,500 (15% of the 1861 population, 37,658). Structural economic problems can be traced back to the early 1830’s with the painful decline of the handloom weaving industry but the 1860’s crisis was directly attributable to the cotton famine caused by the American Civil War which had a drastic effect on Wigan's mills because of their complete dependence on short-fibre American cottons: in November 1862, the ratio of full and part-time to stopped employment in the Lancashire mills was one-to-one, in Wigan one-to-ten. Inevitably saving levels were affected and there was relatively little building society activity: in the 1860’s there were only three known building societies with 'Wigan' as part of their title, All classes of building construction working and middle-class housing, industrial and institutional buildings were equally affected. Houses that were built in Wigan, though generally no longer smaller in ground floor plan, were decidedly inferior in facilities such as back access, private yard space, privy accommodation, pantry and scullery space.

As such there were few residential areas built to meet the limited demand of better-paid skilled manual and clerical workers: Dicconson Street, off Standishgate and Caroline Street, off Wallgate.

were the only two such developments. Most of the new lower-quality housing was sited either on the edge of the old industrial quarter of Scholes or in the expanding mining area in Whelley and so tended to reinforce existing social area structures: that is the occupational areas of either cotton workers or colliers. The only major modification in the housing and related social area pattern was the building of a new factory suburb at Poolstock in 1850 around James and Nathaniel Eckersleys' mills. This was a conscious attempt to break away from the 'polluting' influence of Wigan to create a new community: houses reflected each social gradation of mid-Victorian society from the villas of the factory managers to the minimal-sized back-street houses of unskilled factory workers; church and schools were bequeathed, even allotments were provided.

Of course such Victorian philanthropy was underpinned by good business sense and an eye to public recognition: Nathaniel Eckersley was mayor of Wigan seven times between 1851 and 1873

An Insanitary Houses Committee was formed. Acting under the provisions of the Housing of the Working Classes Act of 1890, the Committee resolved that large numbers of houses, particularly in Scholes, were 'unfit for human habitation' and at the same time proposed Wigan's first re-housing scheme, appropriately enough, for the Vauxhall Road (Club Row) area. House demolition occurred between 1893 and Working Class Housing.

1896 and after long delays and heavy financial losses, 210 new dwellings were built by the Corporation, the last being completed in 1902. Despite these inauspicious beginnings the Corporation was to become increasingly involved with house building and reconstruction and was finally to recognise failures which had their origins over one hundred years before: 'it is thus evident that private enterprise in building is not keeping pace with the requirements of the population.

CONCLUSIONS

Chapman in his preface to The History of Working-Class Housing writes: In the earlier (Industrial Revolution) period the most recurrent theme is the response of the artisan elite to new economic opportunities and higher earnings. Individually, or in co-operative enterprise, the skilled beneficiaries of industrial change can be seen striving to reach superior standards of accommodation and domestic comforts.

In Wigan there is some evidence that during the 'golden age' of handloom weaving, weavers clubbed together to build their own houses but efforts in this direction were short-lived as the building club principle was quickly adopted by larger capitalist interests responsible for some of Wigan's worst housing.

The demise of handloom weaving, the absence of other skilled but better-paid workers and the influx of large numbers of casual Irish labourers in the 1830’s and 1840’s further ensured a deterioration of housing conditions during the first half of the century.

Indeed the final note on nineteenth-century housing in Wigan must be a pessimistic one. One that sounds the general failure of early building clubs and local authorities alike in providing any marked improvement in working-class housing standards.

Source:

The information in this article was obtained from Nineteeth Century Housing in Wigan & St. Helens by John T. Jackson, B.A.,PhD.